Infectious diseases account for approximately 5% of deaths in the United States annually; their contribution as a secondary cause (i.e. cancer deaths due to sepsis) approaches 15%. Between 2020-2022, COVID-19 was the No. 3 cause of mortality in the United States. Despite the visibility of infectious diseases (ID) physicians during the COVID pandemic, ID is a receding specialty.

There are approximately 14,000 ID physicians in the United States, less than 1% of the physician workforce. The impacts of this shortage are disproportionate. Eighty percent of U.S. counties have no ID doctors, and another 10% have very few. There were 9,136 physicians with active ID licenses by 2018, but recent increases are negligible with only 9,774 reported in 2025. Nearly 50% of ID training programs now go unfilled further contracting the pipeline. Meanwhile, infectious disease threats grow due to climate disasters, vaccine preventable illnesses, obesity, diabetes, immune-suppressing therapies, cancer, organ transplantations, etc.

ID expertise results in shorter hospital lengths of stay, reduced cost and improved outcomes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) epidemiologists respond to disease threats through novel research, outbreak response and guideline creation. The CDC provides infectious disease tracking for domestic and international infectious threats such as avian-influenza, Lyme disease and seasonal outbreaks (e.g., flesh-eating Vibrio bacteria).

Without access to ID expertise, frontline health care workers must further rely on public health guidance to manage threats such as measles, influenza and COVID-19. Unfortunately, some, such as new recommendations for age-appropriate vaccines, are now fraught with political interference from antivaccine voices.

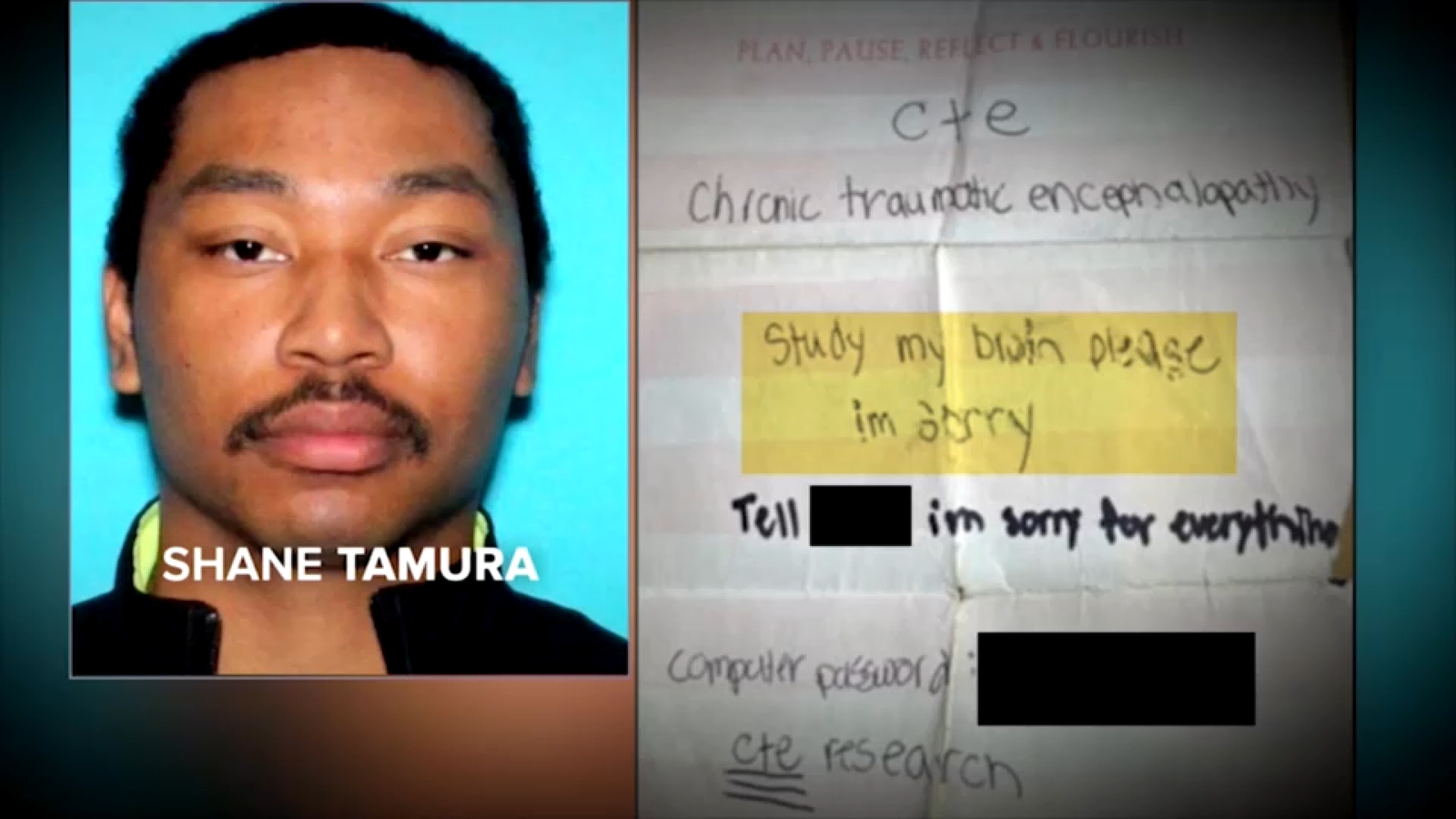

An escalation in threats to public health workers further disincentivizes ID as a career. Recently, a gunman opened fire at the Atlanta CDC campus, an act of unprecedented violence prompting hundreds of HHS workers to sign a letter to Secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr. calling for increased protections and a refrain from unsafe rhetoric.

There are readily available solutions to address the critical shortage of ID physicians, who are among the lowest paid specialties, on average making significantly less than hospitalists who have 2-3 years less training. This is a major recruitment disincentive. Medicare cuts to select specialty reimbursements (including ID) will further decrease salaries and further diminish interest in ID. Policy makers can push for loan repayment for medically underserved areas and for specialties with growing population demands such as ID. Hospital compensation for ID specialists should reflect both clinical productivity and services that enhance hospital safety such as antibiotic resistance reduction programs, infection prevention and transplantation medicine.

Updated immigration policies are vital to staffing medically underserved areas. Unfortunately, the process for foreign-born physicians to legally enter the health care workforce, even in remote and underserved areas, is prolonged and arduous, with no guarantees of a successful outcome. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 successfully transformed the U.S health care system through an importation of physicians and nurses from countries such as India and the Philippines to address healthcare gaps in an aging population. Streamlining pathways for foreign-trained physicians to work in underserved areas while expediting their path to citizenship would immediately strengthen our healthcare system.

Investment in public health is also critical. Stable funding for local and state health departments and the CDC ensures that ID physicians and epidemiologists are recruited and retained. Moreover, this specialized workforce should be guaranteed protection from shifting political agendas. The recent departures of the CDC director and other high-profile leaders over anti-science vaccine policies further erode the morale of the ID-trained workforce.

Finally, public awareness and advocacy campaigns should emphasize the key role ID physicians play as frontline providers guiding safe health care. By communicating the essential public good ID expertise serves, public support can reverse the troubling trends. Every American should be aware that a receding ID workforce in the face of growing health threats will result in worse outcomes, increased health care costs, decreased pandemic preparedness, and an overall sicker nation.

Gonzalo Bearman, M.D., M.P.H., of Richmond is a professor of medicine (infectious diseases) at Virginia Commonwealth University. Rebecca Mullin, M.H.A., of Richmond is associate administrator of the Divisions of Infectious Diseases and Nephrology in the Department of Medicine at Virginia Commonwealth University. Priya Nori, M.D. of New York is a professor of medicine (infectious diseases) at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Opinions expressed herein are our own, and do not necessarily reflect the advocacy position of Virginia Commonwealth University, VCU Health System, the Albert Einstein College of Medicine or the Montefiore Health System.