By Peter Geoghegan

Copyright crikey

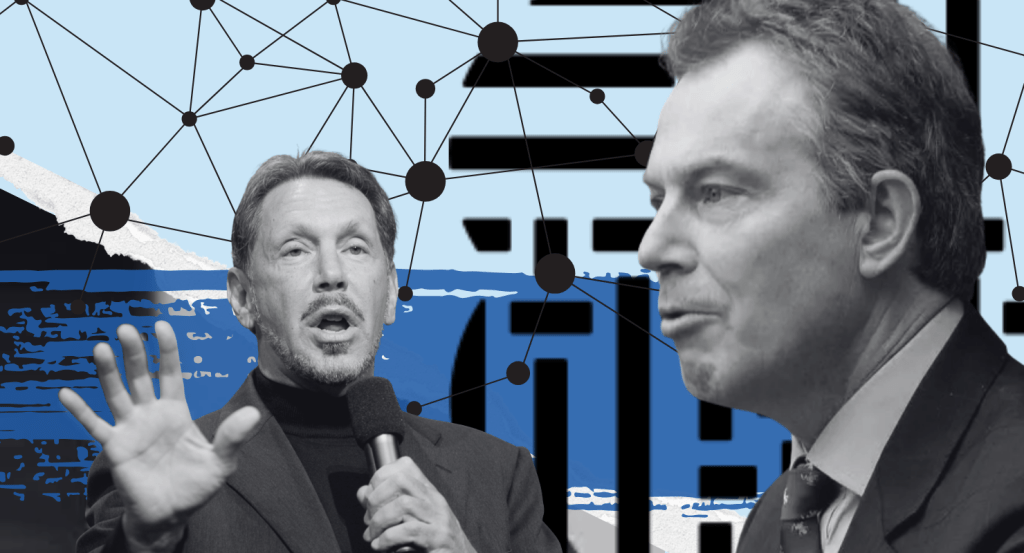

Tony Blair has rarely looked smaller. Seated alone on a vast Dubai stage in February with ranks of premiers and ministers filling the auditorium at the World Governments Summit, he sounded hoarse as he introduced his patron. Looming over him on a giant screen was Larry Ellison, founder of Oracle, whose share price this month briefly made him the richest man in the world.

After a joke about his good friend Elon Musk, Ellison warned the audience that artificial superintelligence was coming sooner than anyone expected. What, Blair asked him, should governments everywhere be doing?

“The first thing a country needs to do is unify all of their data so that it can be consumed and used by the AI model,” Ellison responded.

When his first biography appeared, it was titled: The Difference Between God and Larry Ellison: *God Doesn’t Think He’s Larry Ellison.

Now 81 years old, Ellison’s trademark pencil beard is unchanged from the 2003 cover photo. The billionaire used “we” to refer to all advances in AI. But neither man mentioned the US$130 million that Ellison’s personal foundation invested between 2021 and 2023 in the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (TBI), nor the US$218 million pledged since then.

The owner of super yachts, two fighter jets and a Hawaiian island was specific about which data needed unifying, and he had an example in mind: “The NHS in the UK has an incredible amount of population data,” he enthused, but it was “fragmented”. Down below him, Blair nodded, clutching his TBI-embossed notebook.

Two weeks later, Blair’s institute published a report entitled “Governing in the Age of AI: Building Britain’s National Data Library“. In it, the not-for-profit institute echoed Ellison on the UK’s data infrastructure, calling it “fragmented and unfit for purpose”.

Privately, TBI has lobbied ministers on technology and had policy proposals taken up by government. Critics say that was part of a major influence operation that could yet culminate in US tech firms taking control of Britain’s most valuable data.

TBI is unlike any other UK think tank. Ellison donations have seen it grow to close to 1,000 staff, working in at least 45 countries. It enjoys US levels of funding and influence, so while UK counterparts like Policy Exchange had income of £4.3 million in the past financial year, and the Institute of Public Policy Research registered £4.3 million in 2023, TBI’s turnover was US$145.3 million. The institute has insisted that Ellison is just one among many major funders, and his chief policy strategist, Benedict Macon-Cooney, told media that there was “no conflict of interest, and donations are ringfenced”.

Blair himself takes no salary from TBI, but in recent years, it has been able to recruit from blue-chip firms like McKinsey and Silicon Valley giants Meta. In 2018, before the Oracle founder’s funding surge, TBI’s best-paid director earned US$400,000. In 2023, the last year when accounts are available, the top earner took home US$1.26 million.

One former staff member said the effect of this cash injection was to make the culture “toxic as fuck”, while others described a form of AI boosterism that silenced nuance and pushed the boundaries of lobbying for Oracle.

Investigative newsrooms Lighthouse Reports and Democracy for Sale — working with support from the international reporting coalition Big Tech’s Invisible Hand — interviewed 28 current and former TBI staff, most on condition of anonymity. Supported by public documents and those obtained under freedom of information laws, the testimony describes an organisation unusually close to the British government, that holds joint retreats with Oracle and is willing to engage in “tech sales” with governments in the rest of the world — sometimes to the potential detriment of local populations — under the guise of consultancy.

“When it comes to tech policy,” said a former senior advisor in the UK, “TBI’s role is to go to developing economies and sell them Larry Ellison’s gear. Oracle and TBI are inseparable.”

A TBI spokesperson said: “TBI and Oracle are two separate entities. We collaborate with Oracle to help the work we do in supporting some of the poorest countries in the world, and we are proud of this. […] TBI does not advocate for Oracle’s commercial interests, nor does it advocate for any tech provider.”

Oracle declined to comment when contacted about this article. The Larry Ellison Foundation did not respond to a request for comment.

Land of hope and data

Ellison and Blair’s relationship began as it continues, with the Chicago-raised entrepreneur making charitable donations and later being awarded public contracts. In 2003, Ellison and Blair, then in his pomp, had a photo opportunity at Downing Street to mark a gift of supplies to 40 specialist schools. In tech circles, this is known as “land and expand”. Oracle has since been contracted hundreds of times by the British government and earned £1.1 billion in public sector revenue since the start of 2022, according to data collected by procurement analysts Tussell.

While the Oracle founder was a late convert to US President Donald Trump, the company’s CEO, Safra Catz, worked on his transition team in 2016, and Ellison has been feted by him as “the CEO of everything” since he retook office. Trump named Ellison among the investors set to own a stake in TikTok’s US operations, and the billionaire’s son, David, has taken charge of Paramount after a merger with Skydance, with the new conglomerate reported to be working on an offer for Warner Bros. Discovery Inc., which includes CNN.

As Blair moved from former prime minister to consultant-for-hire to the world’s political and business elite, his relationship with Ellison blossomed. The pair holidayed together off the Sardinian coast. In 2022, the former prime minister recorded a personal video message for Oracle lauding a “shared vision to advance global health”, by building unified electronic health records “stored in one place, where it can be analysed and utilised for the purpose of improving health outcomes”.

There is a reason why men whose fortunes are built on AI investments would target the UK: the NHS and its unique population-level health data. Tech experts talk about Britain’s health records in almost hushed tones. While Europe and the US have some comparable health data sets — such as US veterans’ medical records — none have the depth and breadth of NHS records dating back to 1948. Its potential commercial value, from drugs to genome sequencing, has been estimated at between £5 billion and £10 billion per annum.

TBI, Labour and NHS data

When Labour came to power in the UK last July, it did so promising economic growth and an end to the country’s productivity crisis. Just five days after Keir Starmer was elected, Blair told the TBI’s “Future of Britain” conference that AI was the “game-changer” they were looking for. Within months, Starmer was parroting Blair’s language — and TBI was in the box seat of the government’s nascent AI policy pushing Oracle’s interests and its founder’s worldview.

“There is a real hard sell going on here that says: ‘These kinds of gains are inevitable.’ But they are not,” said Professor Gina Neff of Queen Mary University of London. “TBI is not advocating for building that capacity within the NHS. They are saying: let’s outsource to our buddies.”

TBI was welcomed by a callow Downing Street operation. Peter Kyle, a former advisor in Blair’s second term, was appointed technology secretary despite little experience in the sector, and came into office calling for governments to show “a sense of humility” to big tech companies. TBI had been laying the groundwork before Labour won power. Institute staff advised Starmer’s team in opposition. In May 2024, TBI wrote a report that called for “two radical actions” to fix Britain’s “data access problem”: create a “single front door” providing “seamless access” to NHS data; and host all of this data outside the NHS, while retaining government control of the program.

Less than two months after Starmer’s win, TBI health policy director Charlotte Refsum was invited into the health department to meet digital policy chief Felix Greaves, documents obtained under FOI show. Greaves asked for her help in designing a giant public consultation on GP data and digital health ID. He told Refsum his department needed to “learn lessons” from previous health data scandals that had hardened public opinion against data-sharing with private companies.

Refsum was then given an official role in a government working group advising on data and technology policy in Labour’s 10-year plan for the NHS.

When that plan was published, it contained both of TBI’s two radical ideas. The new “health data research service” would act as the front door to provide “a single, secure gateway to health and care data”, and it would be mainly funded by the government but hosted by the Wellcome medical research charity.

TBI then threw a “summer party” around the launch of the 10-year plan at the London headquarters of the consulting giant McKinsey. The event was co-hosted by the chair of NHS England, Penny Dash — herself an ex McKinsey partner — with “senior leaders from the NHS, private sector, pharmaceutical and biotech companies and investors” among the invited guests.

TBI also appears to have directly promoted Oracle products in its advocacy, even taking swipes at a competitor’s product. In an August 2024 paper on “preparing the NHS for the AI era”, TBI found “good reasons” for building new digital health records with an existing system run by Oracle. It also said that using a system run by rival Palantir — the £330 million Federated Data Platform — would be “a controversial option” and that its product had “been slow to make progress, in part due to opposition from data-privacy groups”.

In a later paper, TBI recommended linking up data from the NHS, DWP and HMRC. All three bodies are Oracle clients, making the firm a clear frontrunner for potential new work.

A TBI spokesperson said: “We don’t advocate for technology solutions because we work with Oracle. We work with Oracle and other technology companies because we believe technology holds the key to the future. TBI is impartial when supporting government clients in technology delivery. The choice of technology provider is solely a government decision. TBI does not get involved in the procurement processes of our client governments with tech companies.”

This is an edited extract. For the full story, go here. A version of this story was also published by The New Statesman.