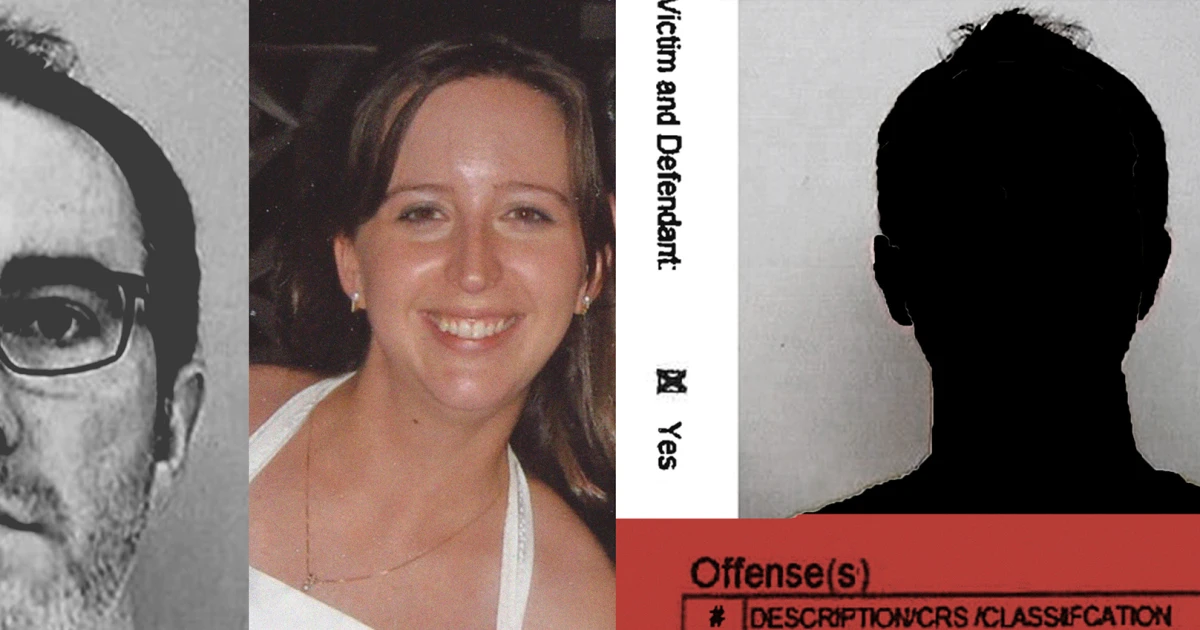

She was stalked and harassed and blamed her ex. Evidence about the true threat came too late.

Earlier this year, Daniel Krug was convicted of killing his wife in an insidious murder plot: He stalked her for months, sending increasingly terrifying messages and posing as someone she hadn’t seen in decades — an ex-boyfriend who’d struggled to get over their breakup.

A cousin of Kristil Krug’s now believes she might still be alive if communications companies had responded faster to search warrants that eventually provided key evidence to authorities investigating the case. That evidence, which helped identify Krug’s husband as the stalker, didn’t come for weeks, until after Kristil, 43, was fatally struck in the head and stabbed on Dec. 14, 2023, in their suburban Colorado home.

In an interview with “Dateline,” the cousin, Rebecca Ivanoff, called on state and federal lawmakers to require companies to respond to stalking-related search warrants within 48 hours.

For more on the case, tune in to “The Phantom” on “Dateline” at 9 ET/8 CT tonight.

“I’m looking at a system here that has a fundamental flaw that we can fix easily,” said Ivanoff, a former prosecutor who specialized in domestic violence cases.

Ivanoff pointed to the link between stalking and homicide — researchers have found that victims are significantly more likely to die at the hands of an intimate partner if they’ve been stalked — and called her proposal “homicide prevention.”

She described the numerous steps her cousin took to protect herself, including installing security cameras, maintaining a detailed “stalker log” that she provided to law enforcement, and eventually carrying a handgun.

“Kristil did everything right,” she said. “The system operated as it’s currently designed, and she still got killed.”

Emily Tofte Nestaval, executive director of a Colorado-based legal service nonprofit that assisted Kristil’s family, called Ivanoff’s 48-hour response window “more than reasonable.” She said her organization has encountered far too many cases “where a more timely and diligent response from communication providers could have — or would have — been lifesaving, as we believe was true in Ms. Krug’s situation.”

The district attorney whose office prosecuted Daniel said it’s critical for companies to respond quickly because “criminals can turn from stalking a victim to killing that victim at any time.”

Brian Mason, district attorney for Colorado’s 17th Judicial District, noted that many stalkers leave a digital trail of evidence that can be used to identify suspects and save lives — evidence that can be uncovered through forensic searches of phones and online accounts.

“When law enforcement sends subpoenas to tech companies for this evidence, it is imperative that these companies respond in a timely and thorough manner,” he said. “Lives are literally on the line.”

In response to questions about how search warrants were processed in Kristil’s case, officials with two of the companies — Verizon and Google — pointed to the many requests they said they receive from law enforcement annually. For Verizon, that number is 325,000, with 75,000 emergency requests, a spokesperson said.

The spokesperson said the company typically responds to those requests in the order received and that it generally doesn’t know the nature of the investigations. They prioritize requests that law enforcement considers “emergent,” the spokesperson said.

Data from Google shows the company received tens of thousands of warrants just in the second half of 2023. In a statement, Google said it prioritizes its responses based on a variety of factors, including whether law enforcement tells them if the matter is an ongoing emergency.

“At Google, we recognize the critical importance of maintaining flexibility in our processes to effectively triage matters based on the individual circumstances, particularly when assessing the presence of an ongoing emergency,” the company said.

A third company, TextNow, did not respond to requests for comment.

The unnerving messages begin

In Kristil’s case, the stalking began 10 weeks before her death. A police report shows the first message arrived Oct. 2 via text: “Hope its OK I looked u up. I go to boulder every few weeks and thought we could hook up. U game?”

The author of the note identified himself as “Anthony” — an apparent reference to Jack Anthony Holland, a man Kristil began dating the summer before college. They were together for just over a year, according to a timeline Kristil provided to authorities, and he periodically reached out and expressed what Kristil believed was an interest in getting back together.

She married Daniel, a financial analyst with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, in 2007. They had three children.

Kristil didn’t respond to the text, or to a series of increasingly hostile messages the next day, according to the police report. But a few weeks later, the messages continued — and escalated dramatically, the police report shows.

One — from an “a.holland” email address — included a vulgar note and a photo of her husband. Others contained sexually explicit photos and appeared to come from people responding to an ad posted on a classified site with Kristil’s phone number. Another message informed her that her license plate was expired. On Nov. 9, a message said: “saw u at dentist.”

A few days later, Kristil got a lengthy message that appeared to threaten her husband’s life.

“Ill get rid of him and then we can be together,” the text said. “So easy.”

In the police report, the detective noted the toll the messages were taking.

“Kristil is very fearful for her safety and the safety of her family,” Andrew Martinez wrote. “There is evidence and admission of repeated following and surveillance of her and her immediate family. The recent communication has caused her anxiety, hyper-vigilance, and paranoia.”

At the time, authorities still thought of her husband, Daniel, as a possible victim. In a sometimes tearful interview with the detective, Daniel described how the stalking had caused his paranoia and anxiety to surge.

“I’m panicking and I’m doing a s— job of protecting my wife,” said Daniel, 44, according to a video of the interview.

Kristil — an engineer who had what her cousin described as a “super-analytical mind” — did everything she could to face the situation head-on, her family said.

She began documenting the messages in a “stalker log.” She hired a private investigator to track down Holland’s last known address, according to her family. She armed herself and went to the Broomfield Police Department, which dispatched undercover officers to keep an eye out for the stalker. (The effort came up empty.)

Although the private investigator had found addresses for Holland in Utah and Idaho, Martinez, the police detective, said he wanted digital evidence proving that Holland was actually behind the messages. If the detective confronted him without that proof, he could “just close the door in our face and that is the end of our case,” Martinez told “Dateline.”

So on Nov. 12, Martinez applied for the warrants for Google, TextNow and Verizon that sought information for the phone numbers and email addresses associated with the messages, police records show. They were submitted to the companies five days later. There was a typo in the warrant to Google, so Martinez resubmitted a corrected version on Dec. 6. But as the weeks passed, neither of the other companies responded. And in the days after the corrected warrant was filed, Google did not respond either.

That lag wasn’t unusual, Martinez said.

“When we serve a search warrant to any major company, unfortunately, it takes time,” he said. “And a lot of times it takes weeks, if not months for some companies.”

Following the wrong lead all along

On Dec. 6, an email arrived in Kristil’s inbox.

“Hey gorgeous i cant visit u no more,” it said, according to a police report. “No more colorado time. My girlfriend dosnt want us talking witout her. She says u will let cops get me aftr u off him but she dont kno u likei do.”

Eight days later, Daniel Krug summoned police to the family’s house for a welfare check after he said he’d been unable to reach his wife. An officer found her body in the garage, body camera video shows.

She had a substantial head wound and appeared to have been stabbed in the chest.

Authorities raced to track Holland down and — with a warrant for his arrest for stalking — they found him at home in Utah on Dec. 14. With help from a Utah sheriff’s office, they quickly concluded that it would have been “physically impossible” for Holland to have been in Colorado at the time of the killing, according to a prosecutor in the case, Kate Armstrong.

Holland told “Dateline” that he didn’t think he’d get charged after authorities came to his door because he knew he hadn’t done anything wrong.

“I was like, ‘I didn’t do it,'” he recalled telling the officers. “I knew I was OK once the police officers left my house.”

At roughly the same time, investigators reached back out to Google, Verizon and TextNow, which still hadn’t responded to the warrants. This time, with the “exigent” circumstances of a homicide linked to the request, they responded within an hour, according to police records.

That data revealed the stalker used an IP address “similar” to the government building where Daniel worked, according to police documents. Investigators then confirmed it was linked to a public wi-fi network at Daniel’s office building, the documents state.

To Martinez, the revelation was “earth-shattering,” he said. It showed that he’d been on the wrong path the whole time.

To Justin Marshall, the lead homicide detective, that evidence could have allowed them to act sooner.

“If the information that we learned pursuant to exigency had been made available in mid-November, we would have known that every communication had originated at the same location — Dan’s work address,” he said. “We wouldn’t have been as far behind.”

When investigators confronted Daniel with the evidence, he said their new “theory” was wrong and suggested the stalker may have accessed his workplace’s wi-fi, a video of the interview shows.

Authorities came to believe that Daniel had been stalking Kristil — who’d wanted to end their marriage — in an effort to scare her and push her closer to him. He killed her out of fear of being found out, Armstrong, the prosecutor, said.

Daniel was arrested two days after his wife’s killing and pleaded not guilty to charges of first-degree murder, stalking and criminal impersonation. Earlier this year, after a roughly two-week trial where his lawyers pointed to the lack of physical evidence and what they described as sloppy police work that failed to keep Kristil safe, he was convicted of all charges and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Pushing for change

In the months after the conviction, as Ivanoff processed the evidence presented at her cousin’s murder trial, she said one thing became clear: “We have a system failure that needs to be addressed.”

She pointed to how quickly the emergency requests for data associated with the stalker’s devices and email addresses were returned and said it’s clear that the companies can move fast when they want to. Had they moved as quickly as they did after Kristil was killed, she said, perhaps the outcome would have been different.

“They could’ve arrested him weeks before she’s killed, and she could’ve safely planned in a way that could’ve saved her life,” she said.

Asked about Ivanoff’s claim that Kristil might be alive if the companies had acted faster, Google and TextNow did not respond, while Verizon said in a statement that it was “highly unlikely” that any of its data would have identified the source of the stalking messages.

The statement added that the stalking warrant had not been designated as an emergency by law enforcement.

Ivanoff said she is in the beginning stages of reaching out to lawmakers, victims’ rights groups and others in her push for swifter response times to search warrants. But she hopes federal lawmakers enact model legislation that states can adopt.

The benefit is clear for law enforcement and victims, Ivanoff said, but defense attorneys should also support the change. She recalled that there was an arrest warrant for Holland, who she said could’ve been jailed while authorities awaited the digital evidence.

“Think about the innocent person that’s accused having to wait and incur all of the attendant impacts of the full weight of the state’s system being brought to bear on them, losing their liberty, losing their job, losing connections with family, friends,” she said.

Ivanoff’s proposal, which she’s calling Kristil’s Law, “is a fight worth taking on,” she said. “If Kristil could, I think, say anything right now, it would be: ‘Get that done.’”