The script for the new Paul Thomas Anderson movie One Battle After Another has been percolating for more than 20 years, and Anderson has said he only added elements from Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 novel Vineland partway through the process. Vineland was about 1960s radicals dealing with the increased repressions of the Reagan era, and Anderson’s loose adaptation—the film’s credits note that it was only “inspired by” Pynchon’s book—is about radicals in the present day, dealing with the fallout of actions they performed 16 years ago. Each story features a splintered family—a militant mother who rats out her compatriots before going into hiding, a father who goes from an activist to a reclusive burnout, and a teenage daughter whose own politics are just emerging—but that’s nearly as far as the similarity goes. Slate’s Dana Stevens called One Battle “Pynchon fanfic,” and that’s about right.

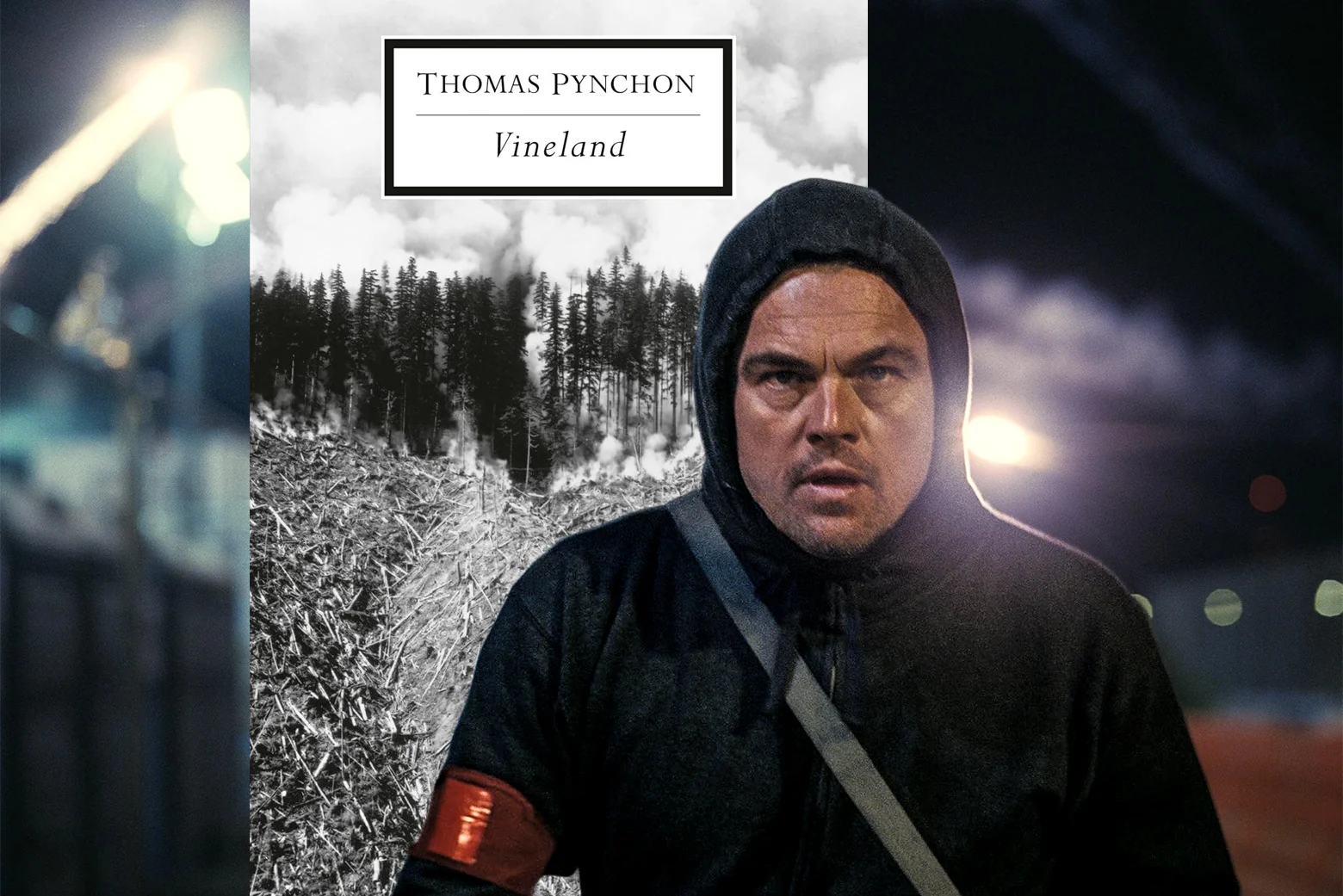

If the experience of watching One Battle is so propulsive that you leave the theater feeling like you haven’t taken a breath in hours, Vineland is far more digressive, switching genres by the page, with a plot that’s more varied than the relatively simple man-tries-to-rescue-daughter story of One Battle. For one thing, Vineland has significant supernatural elements, including the existence of a class of person called a Thanatoid—souls caught between life and death. Thanatoids are stuck in a loop, victims of the American system that kills them. In One Battle, the ghosts are not literal but figurative. You could say Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio) is a metaphorical Thanatoid, left alive but in limbo, condemned to forever lie low.

In addition to this fantasy element, there’s a science-fiction element: the Tube. This is a sort of television that’s so compelling that people can become addicted to it—become Tubefreeks. (If this is reminiscent of Infinite Jest and “the Entertainment,” Pynchon got there six years earlier.) The Tube is, at least according to one younger character in Vineland, one reason why the revolutionary energy of the ’60s dissipated in the ’70s and ’80s. Anderson’s movie perhaps alludes to this in its use of Gil Scott-Heron’s Black Liberation anthem “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” first in its repeated quotation of the lyric “Green Acres, Beverly Hillbillies, and Hooterville Junction will no longer be so damn relevant,” now a decades-later passphrase between Bob and his daughter, and then as a soundtrack to the closing credits. Meanwhile, although the movie ends with Bob staring into his first iPhone as his daughter heads out the door to a protest, the movie mostly avoids replacing the Tube with its obvious contemporary analog. (Of course Bob’s daughter, Willa, played by Chase Infiniti, has a secret iPhone. Teenagers will not be denied.) As timely as the movie often feels, it makes a point of avoiding timestamped references in order to emphasize its own timelessness, and the way these battles keep repeating.

On the other hand, the book’s protagonist, Zoyd Wheeler, is fundamentally the same character as Bob Ferguson: a fumbling old hippie who gets it right in the end. Even something of the spirit of the Vineland side duo D.L. and Takashi, practitioners of obscure Eastern traditions who travel the world performing “karmic adjustments” to help Thanatoids move on, gets transposed into the wonderfully chilled-out and self-assured martial-arts instructor Sensei Sergio St. Carlos, played by Benicio del Toro.

The biggest departure Anderson makes from Vineland is in the relationship between the mother figure, Frenesi Gates (Perfidia Beverly Hills in One Battle, played by Teyana Taylor) and the villain, Brock Vond (Col. Steven J. Lockjaw, played by Sean Penn). In Vineland, Frenesi is white—not only white, but with very blue eyes Pynchon calls “fluorescent.” In changing the character into a Black woman, Anderson creates a new, more personal motivation for Lockjaw’s fascination with her: He’s a racist who secretly desires Black women above all others. This wrinkle also provides rationale for the murderous spree in the final act of the movie—Lockjaw needs to find and wipe away all evidence related to his affair with Perfidia, up to and including Willa herself, in order to enter into the ranks of the elite white-supremacist secret society, the Christmas Adventurers. (This group is another Anderson invention, and a wonderful one.)

In every way, Perfidia is a more forceful and memorable character than Frenesi, a person who is such a snitch that she’s included on the TV Tropes page for “chronic backstabbing disorder.” One Battle’s French 75 is far more violent in its actions (robbing banks, freeing migrants, bringing down power grids) than fps24, the film collective that Frenesi belonged to, which seems to see activism as more of a matter of witnessing. If we see Perfidia wielding a gun, we see Frenesi with a camera. If Perfidia is the one who rolls through the ICE encampment finding the leader to zip-tie, Frenesi, secretly a double agent for Brock, plants a gun and then runs away into witness protection. Perfidia is a rat, no doubt, outing her comrades in exchange for good treatment, but then she runs away from witness protection into Mexico (and then, we hear, possibly Cuba or Algeria). Frenesi cowers in a succession of secret locations, living off the government’s dime. Frenesi’s mother, Sasha, describes her as having a habit, “developed early in life, of repeatedly ankling every situation that it should have been her responsibility to keep with and set straight.”

Brock Vond plays Frenesi like a fiddle. He’s a place for Pynchon to think through the secret attraction revolutionaries may have for fascism, a “charismatic little man” Frenesi can’t stay away from. Frenesi describes herself as having an attraction to “uniforms.” Sasha, herself a lifelong radical coming from a politically turned-on family, recognizes herself as having “a helpless turn toward images of authority, especially uniformed men.” Sasha thinks she passed this trait on to Frenesi: “some Cosmic Fascist had spliced in a DNA sequence requiring this form of seduction and initiation into the dark joys of social control.” In an incredible passage, Pynchon writes that Sasha has come to an understanding of her own psychology, accepting “the dismal possibility that all her oppositions, however just and good, to forms of power were really acts of denying that dangerous swoon that came creeping at the edges of her optic lobes every time the troops came marching by, that wetness of attention and perhaps ancestral curse.”

Anderson will have none of this idea. In One Battle, Lockjaw is a figure of fun from the minute he comes on screen, when Perfidia wakes him up in the middle of the night and commands him to “get it up” as she takes control of the detention facility he’s commanding. (The sight of Lockjaw, pants-tented boner leading the way as he exits his office at gunpoint, was the first laugh moment of many for the audience at my screening.) Lockjaw is a Strangelovian figure, a fascist clown, from his name to his stick-up-the-ass gait to the tight t-shirt Willa calls him out on when they finally meet. The idea of Lockjaw having charisma, let alone being attractive, is unthinkable, and the scene at the nunnery where he holds Willa so he can determine her paternity is deeply upsetting, even nauseating.

Not so the parallel scene in Vineland. At the end of the novel, the Willa character, Frenesi’s daughter Prairie, whom Zoyd has raised, lies in a sleeping bag in the woods, while Brock Vond scouts the hills in a Huey helicopter. Wearing “flak jacket and Vietnam boots, posing in the gun door with a flamethrower on his hip,” Vond is a terrible sight, a classic Reagan-era action hero of his own creation. He finds Prairie, and winches himself down until he’s hovering right over her body, “where she could stare into the dim face, backlit by the helicopter lights.” She lies there, “in her childhood sleeping bag with the duck decoys on the lining,” and sees his face glowing “unusually white.” He tells her he’s her true father, and she comes back with a smartass, Willa-esque retort: “You can’t be my father, Mr. Vond…my blood is type A. Yours is Preparation H.”

Even though she says the right thing at that moment, Brock Vond has powered his way into Prairie’s mind, in a way Willa is never swayed for a minute by Lockjaw. Having escaped Vond’s clutches, Prairie returns to the clearing where he saw her. The very end of Vineland is Prairie in this clearing, wishing Vond would come back. “He had left too suddenly. There should have been more,” Pynchon writes. She knows he’s gone forever (it’s ambiguous, but the novel suggests that he’s died and become a Thanatoid), and that makes it easier for her to say into the dark: “It’s OK, rilly. Come on, come in. I don’t care. Take me anyplace you want.” And so we see that the fascist compulsion Sasha diagnosed in her daughter has slipped down, somehow, to her granddaughter.

It’s this idea that Anderson has excised completely from One Battle, by making Lockjaw so unappealing, the Christmas Adventurers so distant and cartoonish, the rest of the federal forces such burly, bearded, MAGA-ish functionaries. Is this an improvement? Pynchon’s vision pins the impulse to capitulate onto women alone, and makes it sexual, and that’s not fair, and also reductive when you look around and see how many men there are wearing face masks and abducting immigrants off the streets in real-life America. Or does this choice make One Battle less interesting, because the evil is so clearly evil? It certainly makes for a more watchable movie.

The most hopeful moment in Vineland is one that One Battle omits, while finding a different way to evoke it. At the annual reunion of Frenesi’s huge extended family, the patriarch—an old union man—reads a passage from Emerson, which he has memorized, and which he recites every year at this event.

Secret retributions are always restoring the level, when disturbed, of the divine justice. It is impossible to tilt the beam. All the tyrants and proprietors and monopolists of the world in vain set their shoulders to heave the bar. Settles forever more the ponderous equator to its line, and man and mote, and star and sun, must range to it, or be pulverized by the recoil.

Just as Brock Vond is stopped in the act of trying to kidnap Prairie, because Reagan rescinds authorization for his operation, so Colonel Lockjaw ends his life gassed to death in an empty corner office, tricked by the Christmas Adventurers he so admired. Just as the extended family rejoices at having Frenesi back from witness protection and with them again, so Willa and Bob, naïfs at combat, manage to reunite over the slain bodies of their enemies. This is the workings of karma, or just the passage of time. Under the teachings of Sensei, we might think of it like the “ocean waves.”