Southeast Asia’s clean energy transition marred by geopolitical and financial risk, survey shows

By Robin Hicks

Copyright eco-business

Southeast Asia’s shift to clean energy is entering a turbulent phase marked less by ambition and more by the struggle to build resilience against geopolitical, financial and systemic risks, a survey by Sustainable Energy Association of Singapore (SEAS) suggests.

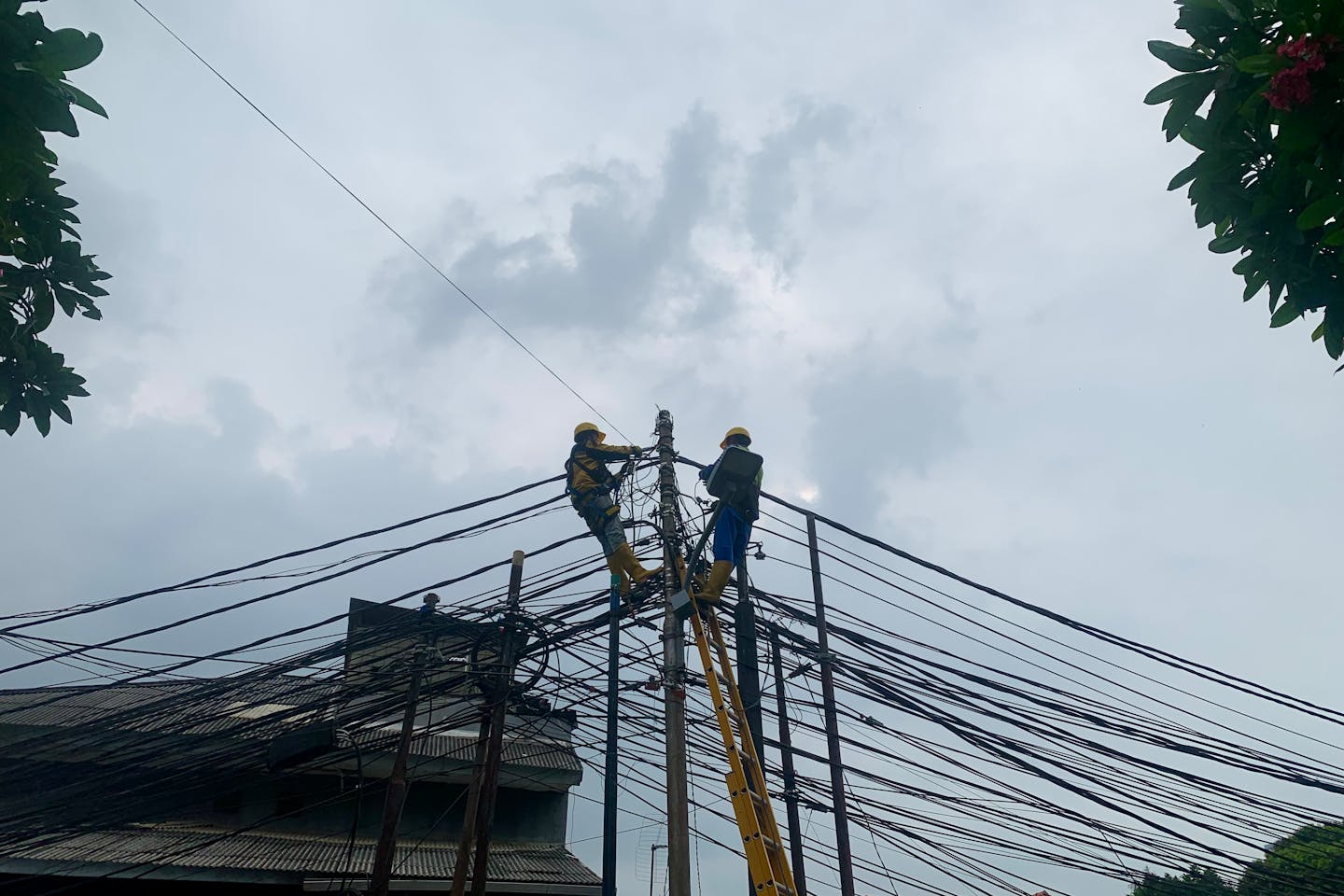

The State of the Energy Transition in ASEAN survey, now in its third year, painted a picture of a region slowly growing renewables capacity but hamstrung by grid bottlenecks, shaky regulations, and weak investment signals.

Singapore continues to be seen as the region’s clean energy leader but its dominance has slipped sharply, the industry association’s study found.

While 95 per cent of respondents ranked the city-state as ASEAN’s top energy transition leader in 2024, that figure has dropped to just 51.4 per cent this year.

The softening reflects the rise of other players and the addition of more survey respondents from across the region.

Malaysia is now regarded as the region’s second most progressive country for the energy transition (14.3 per cent), followed closely by Vietnam (13.3 per cent). The more even spread of leadership perception could be read as ASEAN’s clean energy landscape becoming more competitive – or as a sign that Singapore’s influence is waning.

Despite its fading status, Singapore is still expected to lead on carbon pricing and the creation of a unified regional carbon market (29.5 per cent), as well as solar integration (21.9 per cent).

Singapore’s decision to delay the introduction of mandatory disclosure rules for smaller listed firms by five years – a move that undermined its reputation as an early mover in the region and set it behind Malaysia for climate disclosure – was made after the survey was done, in late August.

Some 105 professionals in energy, finance and academia across Southeast Asia participated in the survey from mid-August to 22 August.

Entrenched barriers, emerging risks

Respondents identified familiar obstacles to scaling clean energy in Southeast Asia: outdated and fragmented grid infrastructure (73 per cent), regulatory uncertainty (67 per cent), and financing constraints (56 per cent). Supply chain instability (41.9 per cent) and skills shortages (25.7 per cent) add to the headwinds.

External shocks are now a central preoccupation. More than half of respondents (52.4 per cent) cited regional conflict and political tensions as the top threat to the transition, followed by energy protectionism (45.7 per cent) and supply chain disruptions (41.9 per cent).

Two-thirds of those surveyed said ASEAN urgently needs stronger cross-border coordination frameworks to protect against energy supply chain disruptions.

“The optimism for technology is now tempered by a sober recognition that systemic readiness for geopolitical and supply chain shocks will make or break ASEAN’s net-zero ambitions,” said SEAS chairman Edwin Khew.

ASEAN countries have a range of decarbonisation ambitions, with only the Philippines and war-torn Myanmar not having set a net zero target. Most countries – Brunei, Cambodia, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam – have set 2050 net zero targets, with Indonesia (2060) and Thailand (2065) committing to decarbonise later.

Despite mounting transition risks, confidence in certain technologies remains high, according to survey respondents. Solar is still viewed as the most scalable renewable energy in the next five years (83.8 per cent), followed by green hydrogen (57.1 per cent).

Investors are showing greater pragmatism, prioritising capital allocation to grid upgrades (41.9 per cent) and energy storage (65.7 per cent) – the infrastructure needed to stabilise grids that are taking on intermittent power sources.

For the third year running, regulatory uncertainty is cited among the top barriers to investment.

“Capital requires certainty,” said Sharad Somani, head of infrastructure for professional services firm KPMG Asia Pacific. “The persistent citation of regulatory uncertainty as a top barrier for three years running is a clear call to action for harmonised policies and bankable project structures.”

The survey suggests a steady shift in priorities over three years. In 2023, ASEAN’s grid potential and governance reform topped the agenda. In 2024, focus shifted to clean energy investment and carbon markets. This year, resilience is the focus – with supply chain stability and cross-border coordination dominating concerns.

Looking at the year ahead, Kavita Gandi, SEAS’ executive director, told Eco-Business that she hoped that ASEAN could continue to work better together as a bloc, so that countries with different levels of development, capacity and technology could exchange renewable resources.

“In the past, there was little economic incentive for countries to cooperate. Everybody was doing their own thing. But now, there is an economic proposition – and I feel that that should be the story for ASEAN’s energy transition,” she said.

Gandi acknowledged that energy companies must give stronger consideration to the responsible siting of projects as the sector gains momentum in Southeast Asia, with a growing number of clean energy projects facing opposition from environmental groups in Indonesia and the Philippines.

“Some host countries have lax environmental standards, and have not been enforcing environmental impact assessments. Some companies priotise profits over planet. We don’t just want a transition – we want a just transition,” she told Eco-Business.