By New York Times

Copyright staradvertiser

WASHINGTON >> Every four years U.S. intelligence officials have published Global Trends, a public document that predicts what challenges the United States — and the world — will face in the coming decades.

With the intelligence community often focused on immediate issues, the Global Trends report has taken a longer-term look. Past editions warned of threats and shifts that came to pass, including climate change challenges, new immigration patterns and the risk of a pandemic.

But the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, led by Tulsi Gabbard, is eliminating the group that compiles the report.

Some of the warnings, most notably on climate change, had become politically inconvenient, according to former officials.

Gabbard’s office, in announcing the decision, said the National Intelligence Council’s Strategic Futures Group had “neglected to fulfill the purpose it was created for” and had pursued a partisan political agenda.

“A draft of the 2025 Global Trends report was carefully reviewed by DNI Gabbard’s team and found to violate professional analytic tradecraft standards in an effort to propagate a political agenda that ran counter to all of the current president’s national security priorities,” the office said.

The elimination of the office last month was little noticed because it came amid a flurry of activity by Gabbard, including the closure of the National Intelligence University and sharp cutbacks of officers working on foreign malign influence and election threats.

Defending the move, Gabbard’s office highlighted what it said were problems of tradecraft, or the methodology used to gather information and analyze intelligence for the report.

Until recently, the Global Trends report was viewed as an objective look into the future by intelligence experts during both Democratic and Republican administrations. But like so much in the Trump administration, what was once considered apolitical is now labeled political.

Gabbard eliminated this year’s report and the team that crafted it with a stroke of her pen. If a future administration wants to revive either, it will not be as easy. While traditionally released in the first months of a new administration, the reports represent months of work by intelligence officers working under the previous White House.

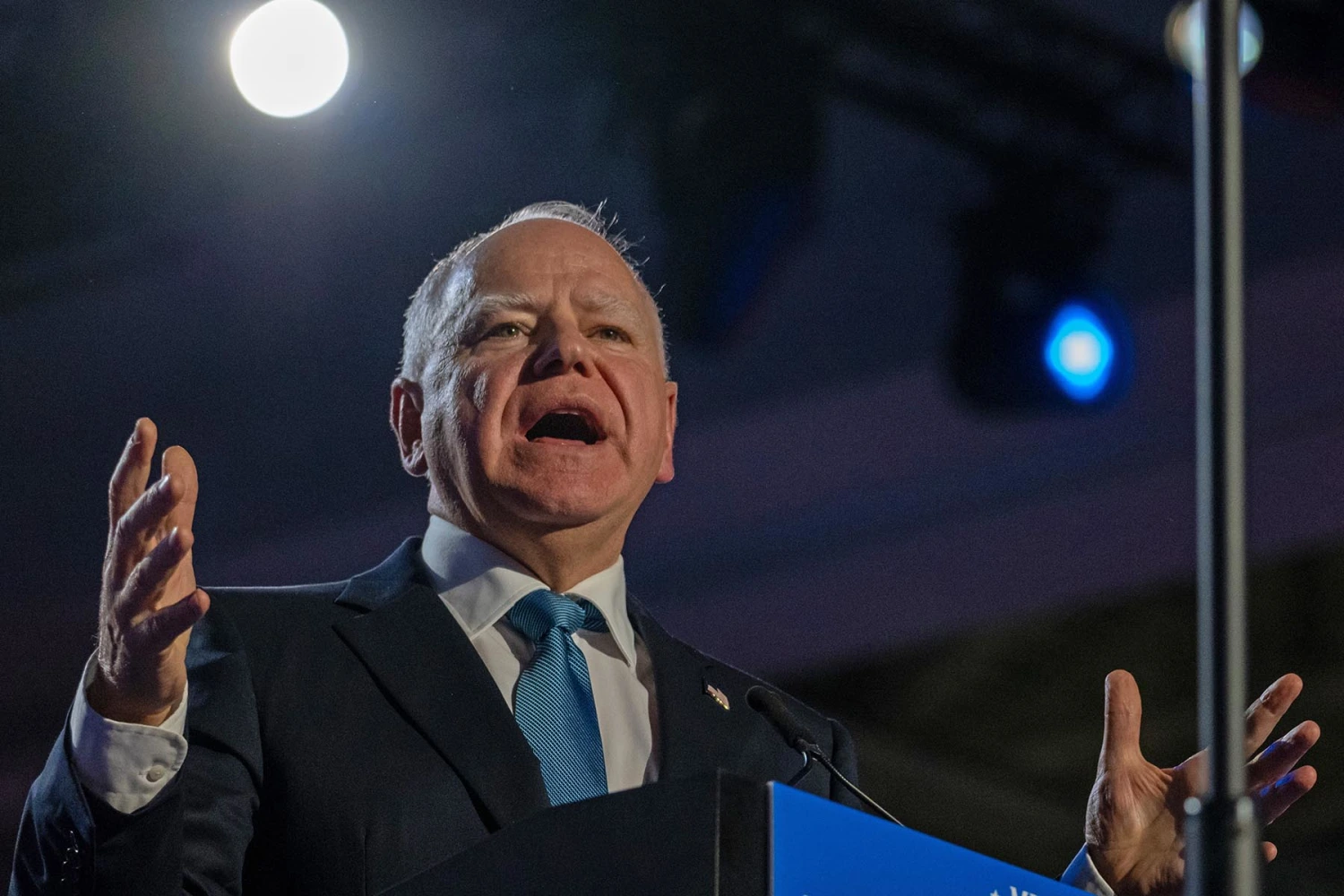

Speaking Wednesday at The New York Times’ Climate Forward conference, Jake Sullivan, the Biden administration’s national security adviser, rejected the argument that intelligence officers were raising concerns to pursue any sort of political agenda.

Sullivan noted that turning away from thorny global issues like climate change would not stop them from posing a threat to the United States, and the world.

“The United States is not going to be as prepared and as capable to contend with this challenge going forward,” he said.

Sullivan lamented that cuts and firings in the intelligence community had fallen heavily on career professionals.

“To have the director of national intelligence cast aspersions upon the professionalism and public service of dedicated people, I just find basically offensive and wrong,” he said.

Gregory F. Treverton, the chair of the National Intelligence Council under President Barack Obama, also took issue with Gabbard’s criticism. He said work on the report helped develop new ways of gathering and analyzing intelligence. The 2017 Global Trends report was developed with the help of focus groups around the world.

“I lament its demise — it was a good exercise in developing tradecraft,” Treverton said. “Obviously, they didn’t like it, didn’t find it necessary. Obviously, they don’t find much intelligence necessary.”

The Trump administration has dismantled a number of national security groups looking at long-term trends. At the Pentagon, the Office of Net Assessment, which had helped senior leaders think about the future of war, was shut down in March.

The Global Trends project began in 1997, before the establishment of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, and released a report every four years that looked years into the future.

The 2017 report overseen by Treverton, for example, discussed the possibility of a pandemic plunging the world into economic chaos. While it forecast that a pandemic would begin in 2023, as opposed to 2020, its warnings about travel restrictions, economic distress and isolation were prescient.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2025 The New York Times Company