People aren’t wrong to fear for the health of US children and doubt our readiness to deal with deadly diseases. Measles has surfaced in Texas, Utah, Arizona, and even Manhattan. Six schools had to close in Milwaukee last spring after the CDC’s lead poisoning prevention team was felled by RFK’s downsizing. The Division of HIV Prevention is another victim. And now, RFK and President Trump have launched a war on Tylenol, further eroding confidence that science is driving policy.

But Americans also deserve honest reporting and global context, even when it may lend credibility to an individual or idea associated with the dark side. And some recent changes in the CDC’s vaccination recommendations, which have been met with horror and condemnation in various news accounts, are, frankly, unremarkable.

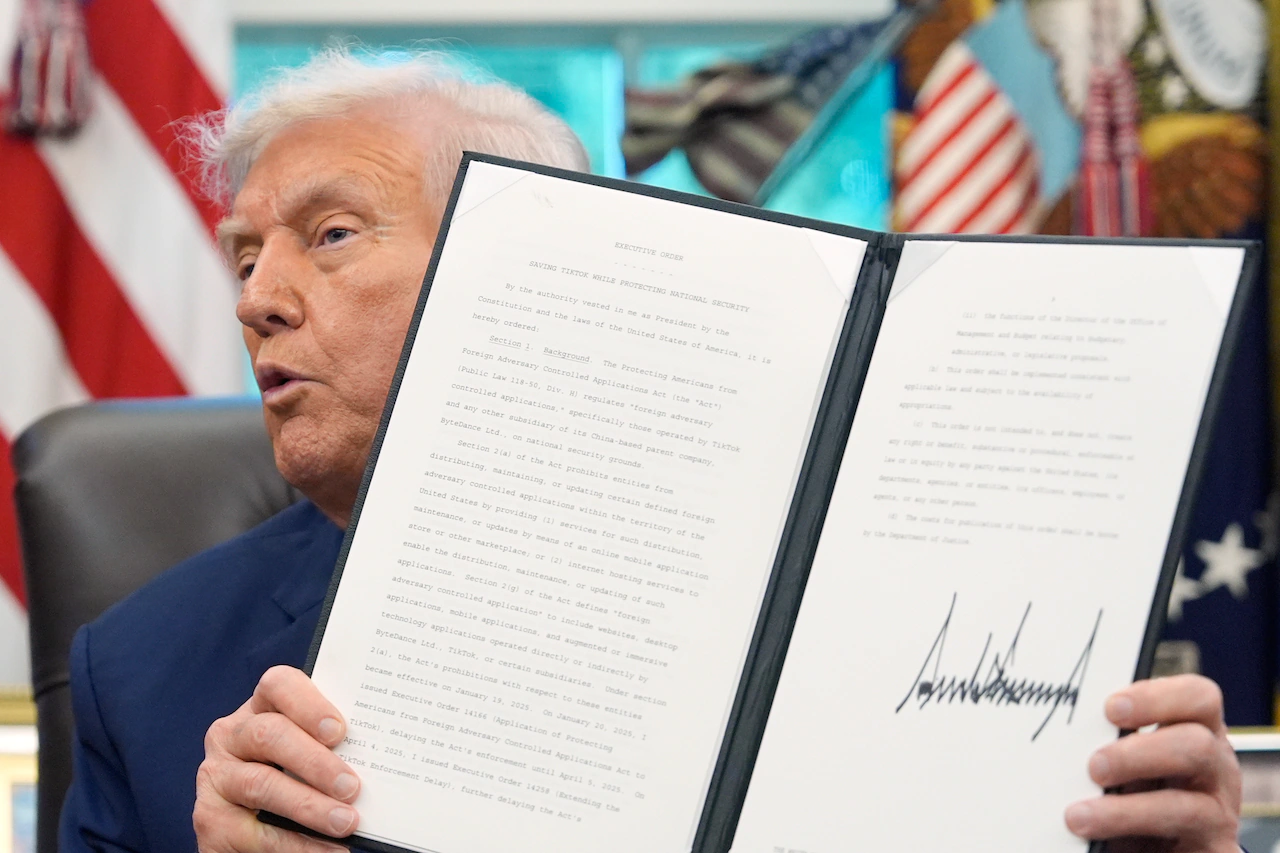

These changes arose last week, when the newly reconstituted Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP) met over two days. COVID-19 boosters are now advised only for seniors and people with underlying health issues. ACIP also voted to push the minimum age for the combined vaccine for measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) to 4 years old, instead of 12 months, because of evidence that the formulation is associated with a small risk of febrile seizures in those younger. (To be clear, the MMR and varicella, or chicken pox, immunizations are still recommended to begin between 12 and 15 months, just separately.) The committee also considered whether to pull back the standing order that all newborns get a dose of hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth. (It decided to postpone the vote.)

The CDC is obviously in turmoil. Its headquarters were attacked by a gunman who killed a police officer. Six hundred people were laid off. Susan Monarez, promoted to lead the CDC in July, was forced out a month later, in her own words, for “holding the line on scientific integrity,” which led to resignations by high-level colleagues. Some have said the CDC is “crumbling” and ACIP “obsolete.” Congressman Ami Bera, a physician and Democrat from California, told reporters that the new committee makeup is “really dangerous and people are going to die.”

It’s understandable that people may not trust the advice coming out of such a beleaguered institution. But ACIP’s recommendations are in line with what is already done in other high-income countries.

For example, in the United Kingdom, Japan, and most European countries, the hepatitis B vaccine is recommended at 4 or 6 weeks of age — and at birth only if the mother is infected.

Three-quarters of EU countries, including France, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, don’t have chicken pox on the immunization schedule at all. In Japan, where the vaccine was developed, the shot is voluntary and only 40 percent of kids receive it. As one paper notes, countries face “health investment trade-offs” in deciding whether to recommend it.

In other words, there is no single evidence-based schedule. Doses and timing vary among countries that are our peers economically and scientifically.

Some media coverage of the proposed changes has been hyperbolic or flat-out wrong. There was some reporting that the committee might recommend delaying the hep B shot until “later in childhood,” possibly age 4, unnecessarily stoking anxieties. The 19th, an online news site, equated any delay with misinformation and MAHA influencers, suggesting “these early decisions on behalf of a newborn can be effectively used as a litmus test of fitness for motherhood.” Demetre Daskalakis, former director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told MedPage Today that he resigned in part because of changes to COVID-19 vaccine recommendations for children and pregnant women made “without scientific basis.”

The truth is that since 2023, most high-income countries and the World Health Organization have not recommended COVID-19 boosters for kids or healthy younger adults. “Evidence is becoming clear that all the current vaccines provide only modest and short-term protection against infection and therefore against transmission,” reads the UK’s Health and Security Agency guidance, published in early September. It says any protection from a booster dose declines “to negligible levels” within three to four months.

In June, the EU’s Centre for Disease Prevention and Control reiterated that COVID “vaccination efforts should focus on protecting people at risk of progression to severe disease, e.g. people aged over 60 years and other vulnerable individuals irrespective of age (such as people with underlying comorbidities or the immunocompromised).”

It turns out that ACIP under the Biden administration was poised to make similar changes to COVID vaccine recommendations before it was disbanded. “In general, what the ACIP did over the last Thursday and Friday was come towards a more harmonized strategy with other major international bodies,” says Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease physician at the University of California, San Francisco.

Nonetheless, she does not support the other changes to the childhood vaccination schedule and takes issue with the committee’s “excessive focus on safety.” “Vaccines are extremely efficacious and have saved many lives,” she says.

Gandhi was among the few liberal-minded physicians during the pandemic who volunteered hours as a CDC watchdog, bravely facing the Twitter mob to point out the many instances when consequential decisions were being made without a scientific basis or a careful weighing of costs against benefits.

For instance, Gandhi compiled data from around the world showing that people who had contracted the virus acquired strong immunity — a textbook concept that was continually put down as an anti-vaccine ploy. She and others argued that whether a person had gained some immunity should be taken into account when prioritizing limited vaccine supplies and considering vaccine mandates. Neither happened.

As data emerged in the CDC’s own journal in January 2021 showing that kids could return to school safely, she coauthored an op-ed arguing that the agency wasn’t following its own evidence in continuing to advise 6 feet of social distance. We’ve since learned that this directive — which had devastating effects for children’s learning and mental health and led hospitals to maintain policies that isolated loved ones as they lay dying or giving birth — was based on little more than a hunch.

Unlike the Trump administration and those whose resentments fuel vengeance, Gandhi does not want to see the agency diminished. But “a genuine apology” for mistakes made during the pandemic “would have gone a long way” toward rebuilding trust, she argues. “There was long-term damage to children in having prolonged school closures in the United States that did not mirror what happened in Europe,” she says, “and it was obvious that those school closures fell along political lines.”

The CDC truly faces an existential crisis. All the more reason that Americans need now what we needed during the pandemic: a collective, open-minded, nonpartisan approach to matters of public health. Hasty polarized reactions do little to make Americans safer or healthier.