By Shreya Adhikari,Tanupriya Singh

Copyright idronline

When we picture cities, we tend to think of flyovers, roads, and high-rises. But as climate risks such as heatwaves, flooding, and air pollution intensify, it is the overlooked assets of parks, lakes, and wetlands, known as blue-green infrastructure, that could determine whether our cities remain liveable. However, unchecked and rapid urbanisation is steadily eroding these natural buffers, leaving our cities more exposed than ever.

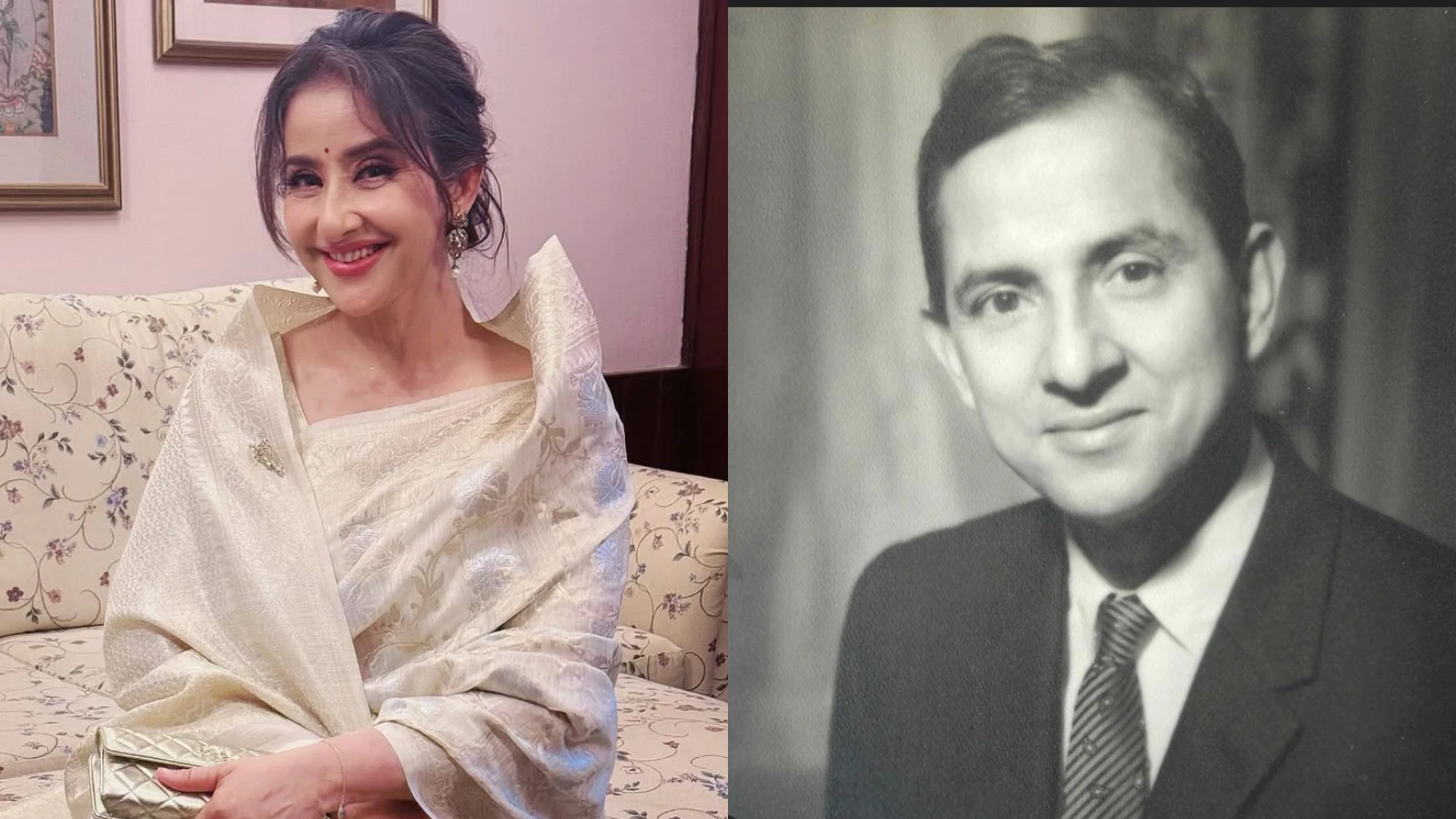

In this interview, Jaya Dhindaw, executive programme director for the Sustainable Cities programme at WRI India, explains why blue-green infrastructure must be viewed not as a luxury but as an essential component of urban planning and design. She also discusses why planning and policy often overlook such infrastructure, despite its various benefits, and delves into the critical role that citizen demand, community stewardship, and interdepartmental collaboration can play in the creation and preservation of blue-green spaces.

Each year we hear about temperatures rising and new climate thresholds being crossed. In that context, why are blue-green spaces becoming so important for cities?

Jaya: Blue-green infrastructure, which includes everything from parks and tree-lined streets to wetlands and water bodies, plays a key role in strengthening climate resilience. In cities specifically, it helps moderate hyperlocal temperatures, reduce the urban heat island effect, and provide shade and thermal comfort during heatwaves. From an ecological standpoint, it supports urban biodiversity, absorbs rainwater, and helps mitigate floods.

While these benefits are fairly well documented, what doesn’t get spoken about enough is how these spaces intersect with the lives of people who are most vulnerable to extreme weather events in cities: street vendors, construction workers, delivery personnel, and daily-wage earners. In urban India, where more than 80 percent of the workforce is informal, millions of people spend most of their day outdoors. For them, blue-green spaces aren’t just ‘nice to have’—they’re essential sites of rest, shade, and recovery. These spaces also contribute to better air, mental health, physical well-being, and overall quality of life. In other words, they create healthier environments for everyone, while offering necessary safeguards for those who need them most.

For vulnerable groups that have the least social and economic safety nets, and have contributed the least to the climate crisis, blue-green spaces often become a critical line of defence against climate shocks. Yet their needs are rarely placed at the centre of how cities are planned or who they are planned for. Climate and urban planning, as it stands, often disregards the everyday realities of people who spend most of their lives outdoors. However, if we’re serious about equitable and resilient cities, we can’t ignore this intersection when talking about the crucial role of blue-green infrastructure.

You mentioned the health benefits that blue-green spaces can offer. Yet this linkage doesn’t seem to feature strongly in planning or policy discussions. Why do you think that is?

Jaya: There is certainly a lack of conversation on that front. But there is growing evidence that blue-green spaces do have a profound impact on public health, both physical and mental. For example, access to natural spaces is associated with lower rates of cardiovascular diseases, improved respiratory function, and better child health outcomes. Additionally, the World Health Organization and the National Institute of Health have shared evidence on how access to natural spaces can lead to better mental health outcomes and reduce depression, anxiety, and stress.

This becomes even more significant in low-income neighbourhoods, where construction quality is poor and the materials used are often highly heat-absorbent, so the homes themselves can become heat traps. On top of that, a large share of informal workers spends most of their time outdoors, which makes access to shade and cool resting spots vital for their health.

There’s another dimension here too. In low-income communities, blue-green spaces aren’t just about cooling or physical health–they also enable social cohesion. They become spaces where people can gather, support one another, and build community, which in turn reduces stress and isolation.

I think there are two main reasons that blue–green spaces are rarely recognised as critical public health infrastructure in India.

Blue-green spaces are seen as a luxury rather than as vital infrastructure.

One is that our government departments often end up working in siloes. The ministries of health, environment, and urban development don’t collaborate with each other meaningfully to devise solutions that offer multiple benefits across the board. Planting a tree, for example, is not just beautification. It improves air quality, reduces heat stress, contributes to better health outcomes, and even increases the value of land in the area. But because departments don’t work together, it gets reduced to this single-purpose exercise. And when there’s no effort to quantify the health benefits or the preventative benefits, it doesn’t get the political attention it deserves. And increasingly, it’s clear that when considering mandates that require interdepartmental collaboration, the things that don’t fall neatly within a single department’s scope are the first to get sidelined. Collaboration sounds good in theory, but in practice it’s often seen as idealistic, too difficult, and fraught with questions such as ‘who funds what?’. The moment you need multiple departments or agencies to come together, it tends to fall by the wayside, and we don’t see real action.

The second is the lack of awareness around why these interventions matter. Blue-green spaces are still seen as a luxury rather than as vital infrastructure. What’s missing is evidence that makes the case for why blue-green spaces are valuable, both in the long and short term.

Why do you think urban planning still misses the mark when it comes to incorporating blue-green infrastructure?

Jaya: The underlying problem is that there isn’t enough planning in the first place. As Tier-II and Tier-III cities or even metropolitan cities expand, much of their growth is unplanned. This makes it extremely challenging to protect, enhance, or create public green spaces. This unchecked spatial growth—driven by short-term real estate pressures, contestations over land use, and weak enforcement of land-use regulations, even where master plans exist—means that green infrastructure is often the first to be encroached upon. If you map cities from the 1990s to 2020, the trend is unmistakable: shrinking green cover and widespread ecological degradation.

Policymakers are constantly having to weigh what will give more immediate, visible benefits. And in that equation, blue-green spaces often become the last priority. The Mumbai Coastal Road is one example, and similar tensions exist in almost every city in India. There is immense pressure over how this limited space should be used and who gets to define the public good. Should a coastal route take precedence, or should blue-green infrastructure be prioritised? Is enabling movement more important, or providing access to green spaces? These are questions every city grapples with, emphasising the need for communities, governments, and civil society to come together and make the case for these spaces as essential infrastructure.

But the buck doesn’t just stop with policymakers or planners. Citizens need to demonstrate a greater demand for blue-green spaces as well. While people benefit from cooler neighbourhoods, reduced flood risk, better air quality, and improved health, these advantages aren’t always recognised as linked to green spaces. Ask someone whether they’d prefer a mall or a park, and many will pick the mall because it’s perceived to boost property values and jobs. With minimal citizen demand, green infrastructure becomes politically insignificant. The result is what we’ve seen before and what we are seeing around us: Restoring, building, or planning for blue-green infrastructure rarely makes it into election manifestos. When city agendas are framed, we might hear ‘let’s decongest the city’ or ‘let’s build flyovers’, but green infrastructure rarely features as a critical political issue, despite its long-term benefits.

The impact of this has been grave. In WRI India’s study titled Urban Blue-Green Conundrum, we found that in India’s 10 most populated cities, urban development has contributed to reduced groundwater infiltration, rainwater run-off, and blue and green cover. Bengaluru, for example, has lost more than 103 square kilometres of surface water between 2000 and 2015.

So how do we avoid repeating the same mistakes, especially as emerging cities are rapidly urbanising? How can we ensure that urban planning integrates blue-green infrastructure from the start?

Jaya: The solutions need to emerge on several fronts. 1. Accountability: Institutional accountability and planning reforms are necessary, especially in smaller and mid-sized cities that are rapidly expanding. Instead of just reacting to encroachments, we need proactive protection and enforceable spatial planning that recognises blue-green assets as critical infrastructure. This requires more than token master plans. What we need are regional frameworks that put people at the centre, allow for flexible land use, are rooted in environmental concerns, and are updated regularly. Using tools such as GIS mapping and studying the capacity of an area to handle development can guide better planning and help protect fragile ecosystems. And if fast-growing urban areas build in these safeguards early, they can set the course for more sustainable, responsible cities.

2. Communication: Prioritising communication is key. We need to use data, visual storytelling, and even popular tools such as WhatsApp to make the co-benefits of blue-green spaces tangible—whether it’s reducing health expenditure, cooling neighbourhoods, lowering energy bills, or even raising property values. Interestingly, there are hardly any studies in India that can help shift perceptions by linking property values to the presence of parks or open spaces. Academic institutions play a crucial role by generating evidence that highlights why these spaces matter, and such evidence can help drive citizen demand.

3. Funding: Cities need both mandates and funding to maintain ecological assets. However, blue-green projects, especially in urban areas, tend to be small-scale, so unless they are aggregated, executing them as one-offs can be inefficient. A government-led fund or facility that can consolidate these projects becomes essential.

For instance, climate action plans in both Mumbai and Bangalore already talk about funding and financing mechanisms as well as governance structures that need to be in place. Climate action cells have been created in both cities, and the Mumbai climate budget outlines how activities across various departments can be better aligned with climate objectives. Another example in Mumbai is that of the gardens department, which is working on a nature fund to move beyond piecemeal clean-ups towards systemic protection and restoration of landscapes.

4. Connection: Bringing various actors together so that everyone is pushing in the same direction can be a challenge. This includes aligning private interests, like that of real estate developers, with the city’s goals, thus creating incentives rather than penalties so developers see value in integrating blue-green infrastructure. It also involves ensuring that government objectives and citizen needs are coordinated. Organisations like ours, acting as interlocutors, play a key role. We serve as system orchestrators—surfacing problems, presenting solution options, and connecting diverse stakeholders to enable coordinated action. For example, in our work on nature-based solutions in Mumbai, we created a sandbox for piloting and testing innovative solutions.

More importantly, we convened the entire ecosystem of solution providers, communities, funders, and government to engage in dialogue and co-create interventions. This approach allowed us to generate robust evidence, which in turn enabled these pilots to be mainstreamed and scaled through municipal programmes.

A bridging role can thus help de-risk innovation, align incentives, and create the conditions for ideas to move from small-scale experiments to systemic change.

5. Policy: Existing programmes and policies can be meaningfully leveraged or replicated as well. As part of the Smart Cities Mission, many cities across India have engaged in public space interventions. One such example is Kochi’s Kawaki initiative, under which more than 1,200 native tree saplings were planted to help restore urban groves—safeguarding against the risk of urban heat islands and flash floods. The initiative was funded by the budget allotted to nature-based solutions by the Kochi Municipal Corporation. Furthermore, the project leveraged the Ayyankali Urban Employment Guarantee Scheme, recruiting women workers who were compensated through the scheme to maintain the sites.

You’ve mentioned citizen demand as a key driver. Could you elaborate on how communities can be engaged to create and sustain blue-green spaces?

Jaya: Citizen demand can be a powerful driver for change, but it comes with both opportunities and challenges. In states such as Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, and Maharashtra, strong citizen voices have successfully prompted improvements in public spaces. Grassroots organisations like the Mahila Housing Trust and academic institutions such as Tata Institute of Social Sciences have been instrumental in generating awareness and mobilising communities.

Stewardship emphasises collective responsibility in maintaining spaces for the wider community.

A notable lesson from successful cases, like the East Kolkata Wetlands, is the importance of linking environmental interventions to economic benefits for the local community. In Kolkata, incentives for fisheries helped the surrounding community see clear value in conserving the wetlands, which encouraged long-term engagement.

It’s also critical to distinguish between ownership and stewardship. When communities enhance public spaces, sometimes these areas become ‘privatised’, gated, or restricted, wherein certain residents believe that access to the area should be limited, which undermines its public purpose. Stewardship, on the other hand, emphasises collective responsibility in maintaining spaces for the wider community. It encourages a sense of accountability rather than exclusive ownership, fostering actions for the larger public good.

Practical engagement tools can make a real difference. For example, in Kochi and Mumbai, we’ve conducted mapathon exercises, involving local communities to help identify derelict lands suitable for new green infrastructure. By including them in planning and identifying these spaces, we were able to create interest and accountability. At the city level, handbooks like Greening Mumbai provide a framework for interventions at multiple levels—plot, neighbourhood, street, and city. This helps communities understand their role as custodians of space.

What are your hopes for the future of blue-green spaces in Indian cities?

Jaya: The shift I would hope for is that blue-green spaces, or public spaces more broadly, become a central and non-negotiable part of urban planning conversations. When we are looking at questions like where development should occur, or conducting land suitability analyses in master plans, there must be a focus on engendering the sanctity of blue-green spaces. This means clear demarcation, enforcement, and public instruments to ensure the maintenance of these spaces as well as their integrity. At the same time, communities should understand their role as stewards of these spaces—acknowledging their importance in safeguarding public health; in their recreational use by children and the elderly; and in offering dignity, delight, and a sense of belonging in the city.

I also think it’s necessary to bring this conversation back to vulnerable and low-income communities. When we plan for basic infrastructure such as sanitation, water, and housing, we rarely think about access to blue-green spaces. Yet these are essential amenities, especially in dense, low-income neighbourhoods. Integrating the access to green and blue infrastructure into planning for these communities can help create more equitable cities.

A simple reframe in our collective imagination of blue-green spaces can generate accountability, political salience, and funding, which can then be reflected in formal planning processes. Creating, restoring, and conserving blue-green spaces can yield multiple benefits—reducing emissions, enhancing equity, improving liveability, and addressing the intertwined needs of people, nature, and climate. If we can catalyse a movement around blue-green infrastructure in cities, the positive transformations for both people and the environment could be profound.

Listen to this episode of On The Contrary on building liveable cities. Watch this video on the design of flood-resistant cities. Read this article on rethinking how cities are built to withstand monsoons.