The Big Take

The Network

Jeffrey Epstein’s private emails show the support and advice the disgraced financier got in his “hour of terror.”

Share this article

When investigators were closing in on Jeffrey Epstein, he thought about saying sorry. Merrie Spaeth, a sought-after crisis strategist who once served as the director of media relations for Ronald Reagan’s White House, helped him pick his words.

She sent Epstein three versions of a public apology in February 2008, according to emails obtained by Bloomberg News. The first was meek: “As a child growing up, I was taught to apologize,” it read. “I fervently hope it will be acceptable for me to simply offer to the community my apologies for associating with young women who turned out to be under the age of eighteen.” The second, at just 33 words, offered little more than a “wish to apologize” and a vow to “conduct myself appropriately in the future.” The third, elegiac and cultured, opened with ideas from philosopher William James about the “hour of terror and the hour of satiety.” It described the “substantial” rewards Epstein had reaped by chasing the American dream, evoked introspection—“I’ve been forced to ask myself what’s important”— and culminated in a “public and heartfelt apology.” He had a clear favorite:

From: J. Epstein

To: [REDACTED] <[REDACTED]>

Date: Tue, Feb 26 2008 4:26 AM

Subject: Re: letters

third has promise

Four months later, he pleaded guilty to two Florida state charges, felony solicitation of prostitution and procurement of minors to engage in prostitution, and was taken into custody to serve a sentence that lasted just over a year. Over the next decade, he never made any broad public apology of the sort the three drafts envisioned. The emails from Spaeth, whose connection to Epstein hasn’t been described publicly, span only a few weeks and don’t make clear what happened to the apologies she prepared. Spaeth’s firm was hired through a lawyer “to provide communications options for Mr. Epstein and his legal team,” she said in response to questions for this story. “I ultimately terminated the engagement because of my discomfort with it.”

Her 2008 exchanges are part of more than 18,000 emails from Epstein’s personal Yahoo account obtained by Bloomberg News. That cache reveals a sweeping array of details about his public and private life, including his callous and methodical recruitment of young women, a close partnership with Ghislaine Maxwell that went beyond what either has admitted and adoration from one of the UK’s most influential figures. The emails also provide new levels of detail about Epstein’s other connections—relationships that were less public but nevertheless crucial to him, especially once he became the target of state and federal investigations.

Epstein was drawn to what he saw as the finest things in life. The substantial wealth he acquired after leaving Bear Stearns in 1981 to advise the ultrarich afforded him a Boeing 727, one of Manhattan’s largest townhouses and his own Caribbean island. And when his own hour of terror dawned in 2005, following a tip to police in Palm Beach County from the family of a teenage girl, he didn’t rely on just one champion or defender, his inbox shows, but a collection of elite professionals. Though lawyers, academics and media advisers helped him in different ways and to different extents, his network included past and future White House officials, a top Hollywood publicist, a former child-exploitation prosecutor and renowned researchers, including one on his way to winning a Nobel Prize.

That support for Epstein—who harmed more than 1,000 people, according to the US Justice Department—came when he needed it most. The professionals who surrounded Epstein defended and deflected, coached and countermessaged, burnished and polished. Together, they helped extend Epstein’s influence and freedom, even lending an air of invincibility. His reckoning was postponed until 2019, when federal prosecutors charged him with trafficking minors. Weeks later, he was found dead in jail in New York City awaiting trial.

Epstein’s emails veered between domineering, cloying, comfortable and obsessive, and were often riddled with typos. In response, his advisers and supporters were deferential and even fawning.

➞ Read more about how Bloomberg News vetted Epstein’s emails

In October 2007, when the New York Post reported that Epstein was preparing a guilty plea, one of his many friends at Harvard University got in touch.

“I read the newspapers early this morning,” the neurologist Mark Tramo wrote to one of Epstein’s assistants. “Please remind him that boys from The Bronx (even if they end up at Harvard) have long memories, know all about cops, and stay true to their friends through thick and thin (no less peccadilloes).” Tramo, who is currently listed as an adjunct professor at University of California at Los Angeles, didn’t respond to multiple messages seeking comment.

Listen to The Big Take podcast on Epstein’s Emails

The Academy

Epstein, a former math teacher, wasn’t merely interested in academia. He was fixated, and academics were drawn to him, too. Despite his indictment, he was able to assemble a prestigious network of Ivy League researchers who remained helpful to him even years after he was released from jail.

His connections to academia have been well established. In 2020, a year after the federal sex-trafficking charge, Harvard disclosed in a report that it had accepted more than $9 million in gifts from him between 1998 and 2008. The report also described Epstein’s unusual reach across the university, including access to an office until 2018 and a phone line until 2017. Since then, other institutions have acknowledged their own ties with him, too, helping to shed light on the breadth of his relationships.

The emails obtained by Bloomberg, however, reveal their depth. They detail how key relationships were initiated and maintained and how the research he funded was conceptualized. The emails show how aggressively some researchers prioritized him, even as allegations spilled out into the open.

For them, Epstein represented money, access and a champion. For Epstein, who left college without a degree, they offered bonafides, advice and a willingness to confer on topics both universal and esoteric, including sex and beauty, disease and genetics, and the life of the mind. Epstein was also interested in artificial intelligence—and in emails with a computer scientist, sent right before reporting to jail, he even weighed a “Manhattan Project” for AI.

In January 2006, six months before the indictment, Epstein’s assistant asked about nailing down an appointment for him with Stephen Kosslyn, then-chair of Harvard’s psychology department. “kosslyn is a priority,” Epstein wrote. Within days, the psychologist was proposing a dinner with bigwigs across economics, genomics and limb regeneration to discuss a lab “centered on genetics and the brain” that would explore “far-out ideas such as life extension.” He also helped plan smaller gatherings for Epstein, including “pizza over a table” with him and “The Dersh”—Harvard Law professor Alan Dershowitz, one of Epstein’s lawyers.

Kosslyn, who’s now president of an AI education startup, corresponded that February with geneticist George Church and Gary Ruvkun, a Harvard molecular biologist who won a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine last year. They shared ideas about a project whose “farthest reaching harvard goal” would bring together experts in law, psychology, biology and economics to describe the “pleasure signatures in the brain” that they said could correspond to hunger, sexuality and fear.

In a February 2006 email forwarded to Epstein’s assistant, Ruvkun wrote: “i shall again try to drive home the point about the pleasure genome initiative.” He added this request: “let me know if this subject is too strange for our patron.”

When Epstein received the exchange, he wrote to his assistant:

From: J. Epstein

To: [REDACTED] <[REDACTED]@gmail.com>

Date: Mon, 27 Feb 2006 3:19 PM

Subject: Re: Steve Kosslyn-Interdisciplinary Dinner #2 Mar 13

the patron has no boundaries

It isn’t clear from the emails what money, if any, Epstein gave to the project, though he’d previously donated $200,000 to support Kosslyn’s research, according to the Harvard report. A university spokesperson had no comment for this story. Kosslyn didn’t return calls and messages.

“Dr. Ruvkun attended a large group dinner with academic colleagues to discuss potential research projects in the spring of 2006, prior to any public accusations being made,” said a spokesperson for Mass General Brigham, where Ruvkun has long been affiliated. He had no further contact with Epstein, “did not pursue any of the research areas discussed, nor received any financial support for his work.”

Epstein, meanwhile, was ruminating on the nature of beauty, according to a series of email exchanges. One June 2006 email in his inbox differentiates between the beauty of human bodies and “a Mozart piano concerto, a Ted Williams swing, a Caribbean vista, the fragrance of a gardenia, Euler’s formula.”

Shortly after, Epstein wrote to his assistant that he was planning to contribute to Harvard’s Personal Genome Project, run by Church, the geneticist: Epstein wanted to know if beauty resides in DNA, he said. He was due to spend more than $1 million on the project from 2006 to 2009, according to an itemized budget in his inbox. Church, who leads synthetic biology at Harvard’s Wyss Institute, proposed “possible topics” for one of their gatherings, including “re-engineering humans.” (In response to questions, Church’s lab referred to his apology in 2019 for meeting with Epstein, which cited “nerd tunnel vision.”)

From: J. Epstein

To: [REDACTED] <[REDACTED]@gmail.com>

Date: Fri, Jun 23 2006 5:19 PM

Subject: Re: [REDACTED]: Genetic basis of beauty

I am going to fund the personal genome project at harvard , questions does the beauty reside in the dna,, is the formula more elegatn.. ,, of is it the hunt for complementarity, that determines the eye of the beholder

In the years before 2006, magazines and newspapers had introduced Epstein as a rich and secretive globetrotter who enjoyed the company of young women. But a new kind of Epstein story hit newspapers that July in New York, Palm Beach and Cambridge, Massachusetts: The 53-year-old investor had been charged. In the months after, articles chronicled sworn statements to the police from teenagers about giving him massages in their underwear for cash.

Epstein’s academic ties were helpful as reporters began focusing more intently on him. Kosslyn was vacationing in the “backwoods of nowhere” in August when he let Epstein’s office know about an inquiry he’d received from a Fortune reporter who was working on a “short article” about Epstein. And when a reporter for the Harvard Crimson emailed about a spat that involved Epstein and Dershowitz, Kosslyn sent that along, too:

From: Stephen M. Kosslyn <[REDACTED]@wjh.harvard.edu>

To: jeeproject@yahoo.com

Date: Thu, Jun 14 2007 5:32 PM

Subject: Fwd: Crimson Article: [REDACTED]

FYI: I’ll not respond

In October 2007, Epstein received an email from Howard Gardner, a leading developmental psychologist at Harvard who helped start an initiative on living ethically called the Good Project, which “strives to equip individuals to reflect upon the ethical dilemmas that arise in everyday life.” Gardner said he’d be getting back to him on two requests: “a reading list and advice about offsprings.” Epstein was less than a year away from reporting to jail. “Meanwhile,” Gardner added, “take a deep breath, take one day at a time, and you’ll get through the coming period fine.”

According to Epstein’s inbox, Gardner followed up by recommending novels including Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day and Saul Bellow’s Henderson the Rain King. “As for the other, more personal question that you posed, that requires a longer conversation-whenever you’d like.”

That “offsprings” question may have been “about the possibility of having children,” Gardner told Bloomberg News. “Beyond common sense I did not have any advice on that score.”

Asked why he and so many academics flocked to Epstein, Gardner said he was charming, knowledgeable and “had a sixth sense for what others—including faculty members and senior administrators—would appreciate.” Gardner added that he wished he “had asked more questions, but I don’t even know what questions I would or should have asked.” He added: “I never had the slightest knowledge or even intimation of the darker sides.”

In January 2008, Kosslyn offered Epstein a birthday wish: “May the coming year be infinitely better than the previous one.”

The next month, as reporters chronicled new lawsuits against Epstein by women who said he sexually assaulted them when they were teenagers, a new endeavor was underway. Star researchers across universities made plans to better understand the brain with Epstein’s backing. One of them, Elkhonon Goldberg, a renowned neuropsychologist then at New York University, laid out a plan in a February 2008 email.

“We are quite confident that with your support our Brain can become an exceptional scientific endeavor and we will be proud to name it ‘The Epstein Brain,’” Goldberg wrote, adding a smiley face.

Epstein demurred: “I appreciate the honor, but decline any name association,” he responded. He proceeded to set up an all-hands meeting for the following week. According to emails, the group of researchers was set to include NYU’s Yann LeCun, who is now chief AI scientist at Meta Platforms Inc.’s Facebook AI Research. Goldberg’s $1.3 million proposal to study the “brain dynamics of learning” included LeCun as a co-supervisor of students or fellows.

In an interview with Bloomberg, Goldberg said the project didn’t move forward, Epstein didn’t provide funding and the proposal to name it for him was “obviously in jest.” He added that surrounding himself with prominent researchers may have been a way for Epstein to fulfill a fantasy of being a scientist.

LeCun, who doesn’t come up elsewhere in the email cache, told Bloomberg he’d never heard of Epstein before. “I had no further interaction with Epstein after this one meeting and I did not receive any funding from him. The project never took off. Only later did I learn about Epstein’s reputation and legal troubles,” he added. “As far as I can tell, Epstein’s impact on AI research has been essentially nil.”

In May, Kosslyn wrote that he had “decided to be Dean of Social Sciences” at Harvard. Kosslyn added a month later that he’d love to visit him.

“unfortunately jail starts monday,” Epstein wrote.

From: Stephen M. Kosslyn <[REDACTED]@wjh.harvard.edu>

To: J. Epstein

Date: Fri, Jun 27 2008 8:48 AM

Subject: Re: Checking in

DAMN! Let me know how/if I can help.. s.

The Counselors

Long before Epstein reported to jail, Dershowitz and prominent lawyers from Florida and New York had worked in 2006 to narrow the scope of his prosecution in Palm Beach County. They did it so well that the lead detective flagged concerns to the FBI. After a federal investigation began that May, Epstein’s team added even heavier hitters, with major Washington credentials. They helped bring both cases to a close by negotiating a non-prosecution agreement that spared him from federal prosecution in exchange for his guilty plea to state charges. After about 13 months in prison, Epstein would be a free man for almost a decade.

In early 2006, as Epstein’s legal peril was deepening, he got a note from a Harvard Law School student and research assistant to Dershowitz named Mitch Webber. What email address, read by Epstein alone, would be private, he asked.

Epstein wrote back: “this one.”

It was at the dawn of a career that took Webber to the White House, where he was an associate counsel and special assistant to Donald Trump, into the partnership of law firm Paul Weiss and onto the board of the Louis D. Brandeis Center for Human Rights Under Law.

Though his presence in Epstein’s inbox lasted less than a year, Webber memorialized a key moment in the Florida case. He took shorthand notes during a February 2006 meeting with Epstein’s legal defense team and two members of the Palm Beach County State Attorney’s Office and a detective.

“These girls are self-described prostitutes, they don’t feel harmed, and they’re out for money,” Dershowitz said, according to a memo from Webber that said it paraphrased his notes. Epstein “is decimated already. He hasn’t slept in months. I want to leave here and tell him we’ve got this resolved. Why can’t we figure something out today?”

An assistant state attorney told Epstein’s team her office had an ethical obligation to consult with victims before making any deals. As they discussed possible outcomes, Dershowitz said he refused to make Epstein “into a public pariah.”

Webber, whose work for Dershowitz extended past the Harvard Law commencement that June, went on to field sensitive questions from Epstein. “I’m sorry I was a little confused about what you were asking on the phone,” Webber wrote him. “I se what you were asking now. The question is: what would happen if one were to transport a minor for sex—or transport oneself with the intent to have sex with a minor—into a state in which the age of consent is below eighteen (assuming the minor is above the age of consent in the given state)? And your intuition was right. The answer is that there is no violation of law.”

“let’s also look at sex tourism laws,” Epstein wrote back that August. “going someplace with specific intent ot have underage sex.”

Webber’s last emails in the inbox came that November. “To pretend that Epstein has an unimpeachable, airtight legal defense is disingenuous,” he wrote in one. Another email added: “No matter what happened between Epstein and his masseuses, the fact that they kept coming back militates powerfully against any sort of pressure on Epstein’s part.” Webber didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Not many figures in Epstein’s legal circle have been more closely linked to him than Dershowitz, a central member of his legal team for years. The emails show the depth of the support he gave Epstein.

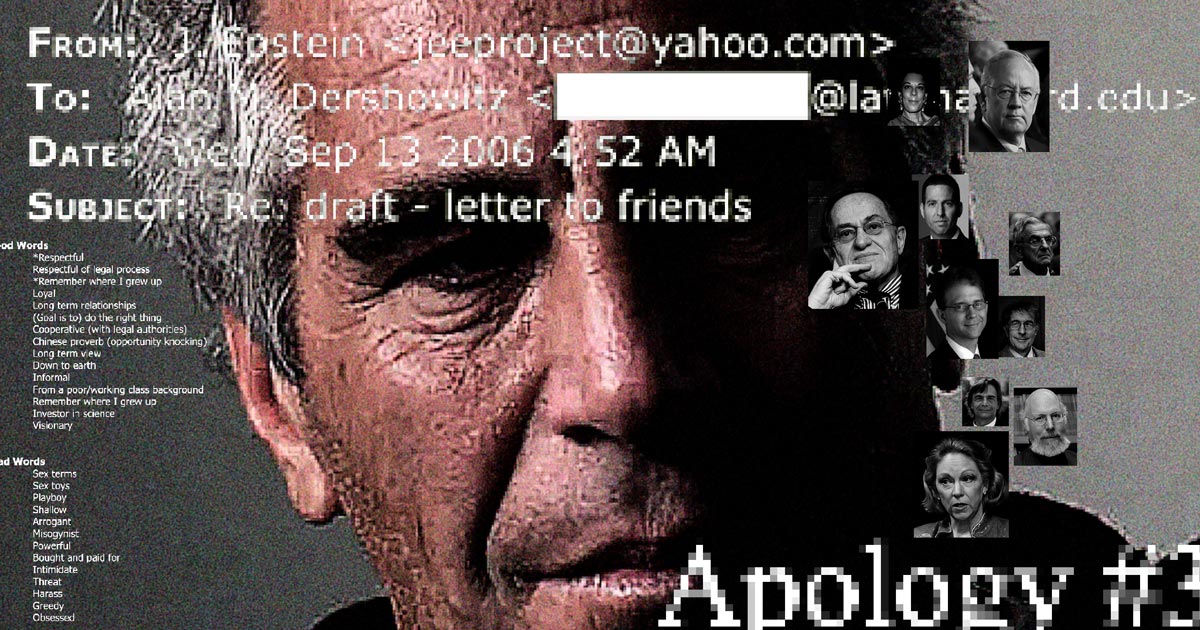

“I am writing this letter to Jeffrey’s close friends as one of his close friends, not as a lawyer,” read a draft of a letter in September 2006. “NO, there was never any underage sex. Absolutely none.” The letter, which closes with “Cordially, Alan Dershowitz,” was flattering and savvy: “We all know Jeffrey is extremely smart, and in fact a little ‘complex.’ However, he is not self-destructive.” It rose to a crescendo: “I know that you wish him well, and I’m sure that as this too will pass, we can all help him bring this difficult time to a forgiving close. When the full story finally comes out, the world will learn what we already know—that Jeffrey is a good person who does many good things.” Dershowitz told Bloomberg that he doesn’t recall the letter.

For Epstein, who was reviewing drafts of the letter, that wording wasn’t enough:

From: J. Epstein

To: Alan M. Dershowitz <[REDACTED]@law.harvard.edu>

Date: Wed, Sep 13 2006 4:52 AM

Subject: Re: draft – letter to friends

I would amend the place where it says he wishes I had cameras in the massage room… IT would be illegal… ANd I think we could do better thatn the last paragraph ,, JEffrey is a “good person”.. great friend. , loyal, funny, generous, not GOOD

Then, in a version that Epstein later sent to himself, there was an edit. “Jeffrey is a very charitable, and caring person,” that copy read. It kept this earlier pledge: “Jeffrey has not approved the contents of this letter, though he is aware that I am writing it.”

“The memos are all privileged lawyer client communications and should not have been provided to you or made public,” Dershowitz told Bloomberg News. “But they show that I was acting as any responsible lawyer should: making the case for my client.” He added that “Epstein was dissatisfied with the deal I helped arrange. He wanted a misdemeanor with no jail time and no sex registration.”

In May 2007, the Assistant US Attorney responsible for the Epstein investigation submitted a 60-count indictment to supervisors. Then, just after prosecutors offered terms that would lead to the non-prosecution agreement, they heard from some of the biggest names in law—including Ken Starr, the independent counsel whose report had led to Bill Clinton’s impeachment. Epstein had called in reinforcements.

Rather than simply seeking advice from them, he told them what to say.

“Starr needs to explain his appearing,” he wrote to his lawyers on Aug. 12, weeks before Starr first met with US Attorney Alex Acosta to discuss the case. “He is not defending my conduct he is defending the constitution.” Epstein went on to propose language and ideas to his legal team, while apparently trying not to offend. “I don’t mean to put words in your eloquent mouth,” he told Starr in June 2008, before offering a numbered list that ranged from legalistic (“we are asking for a de novo review”) to impassioned (“this is not righteous”). Days later, Epstein was incarcerated. In the cache, there are emails to but not from Starr, who died in 2022.

The reach of Epstein’s team was vast. In the weeks before the guilty plea, Epstein delegated work to lawyers including Kirkland & Ellis partner Jay Lefkowitz, Starr, Dershowitz and Stephanie Thacker—who’d spent years with the Justice Department’s Child Exploitation and Obscenity Section and is now a federal judge on the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. Lefkowitz and Thacker didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In total, Epstein paid $4 million to Dershowitz and almost $3 million to Kirkland & Ellis, according to a forensic accountant’s report filed in court records two years ago.

“He essentially fired me and refused to pay what he still owed me,” Dershowitz said. “We ultimately resolved the fee issue but I believe my total fee—which was based on my hourly charges—was far less than what you say.” He later estimated that he made about $3 million after paying out the rest to other lawyers and researchers.

Epstein’s legal fees from 2003 through 2013 hit more than $54 million, according to the accounting report. Yet he came close to spending even more—after the indictment—on a Paris mansion on the Île Saint-Louis that he wanted to make into “a mathematical instiute,” the emails show. A Qatari prince outbid him.

The ‘Good’ and the ‘Bad’

As some of the country’s best-connected lawyers were defending Epstein and elite academics were catering to his intellectual interests, media professionals worked to protect his public image. His publicists and consultants, according to the emails, included veteran executives Howard Rubenstein, Dan Klores and Mike Sitrick. Peggy Siegal, who held sway over some of Hollywood’s biggest movie premieres, emailed after the 2006 indictment to flag a Vanity Fair story.

“Can only assume Jeffrey does not want me to talk to this reporter,” she wrote his team, “not unless he wants certain things said on his behalf.” (Like Dershowitz and Sitrick, Siegal also did work for Harvey Weinstein.) Rubenstein died in 2020. Sitrick said he was retained by Epstein’s lawyers for a fairly short period. Klores and Siegal didn’t return messages.

But it was a former actor who taught Epstein her own communication method in the months before his sentence began.

Spaeth, featured as a teenager in the 1964 film The World of Henry Orient, went on to become a White House Fellow, director of public affairs at the Federal Trade Commission and then the Reagan White House’s director of media relations. Later, after founding her own firm, she advised Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, which sought to undermine John Kerry’s service record during the 2004 presidential campaign. (She was later quoted saying she regretted her involvement.)

According to an email in Epstein’s inbox at the end of February 2008, the two spent time together preparing for interviews, though it’s unclear which ones. Her memo after their session describes showing Epstein “the Spaeth methodology” to answer questions without “being trapped by the parameters.” During their exercise, she emphasized having “material to change the subject” and the “skill to repeat ‘it’s not appropriate to discuss…’ without sounding canned or bored.”

“JEFFREY INTERNALIZED AND ACED THIS EXERCISE IMMEDIATELY,” she wrote.

They came up with “a long list of questions” that, Spaeth predicted “will, alas, almost certainly be permanent features for years to come.” One example: “Mr. Epstein, as you preyed on these innocent young girls, did you actually know any of them were under the age of 18?”

Spaeth coached him to respond by choosing “a phrase like ‘I disagree,’ or one of our favorites, ‘on the contrary.’”

According to the emails, Epstein paid Spaeth $1,900 for consulting earlier that year, and sent an additional $5,000, at least in part for the February work.

“Principles of confidentiality and privilege preclude further comment about the substance of this engagement,” she told Bloomberg News.

Spaeth also helped Epstein tailor his vocabulary. She instructed him to use what she called “Good Words,” such as smart, brilliant and lucky—and avoid “Bad Words,” including playboy, powerful and pervert. She taped him to “benchmark and critique whether he seemed authentic.”

She sent messages for him to focus on. The first one: “I have tried to be very respectful of the legal process.”

Spaeth wrote to his team to say it “was a fascinating session, and I hope he found it useful.”

Months later, as Epstein got ready to serve the jail sentence that so many lawyers had pushed to make so short, he gave a rare interview to the New York Times. His first quote in that story: “I respect the legal process.”

Stay connected: Don’t miss hearing about upcoming reporting: Sign up for the weekly newsletter written by Bloomberg’s senior investigative reporter Jason Leopold.