By Anna Ajayi

Copyright pulse

Part 6 recap:

Jimmy’s escape from the Libyan camps came in the chaos of war. Rebel fighters stormed the prisons, tearing fences and shattering cells, and Jimmy ran through smoke, bullets, and blood until he stumbled free.

Stranded in Tripoli with no money, no papers, and only a rusty razor blade, he hustled on the streets, washing cars, hauling water, and cutting hair anywhere he could, for coins that he and other survivors pooled together. Their eyes fixed on one thing: the sea. When their turn finally came, they climbed into an overloaded rubber dinghy bound for Italy. But soon, water began to fill the boat, panic erupted, and the vessel capsized, plunging Jimmy and over a hundred others into the dark waters of the Mediterranean.

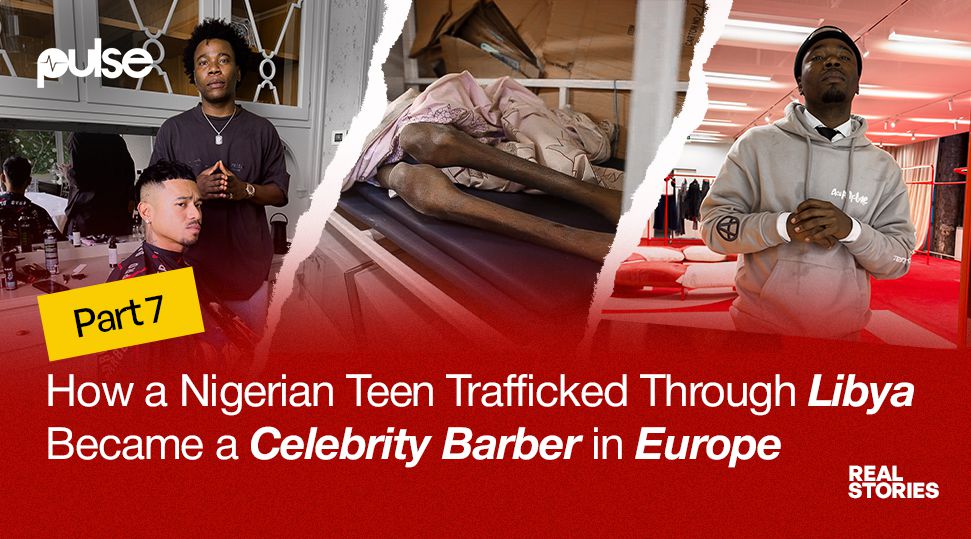

Catch up here: Part 6: How a Nigerian teen trafficked through Libya became a celebrity barber in Europe

It was chaos.

Jimmy looked around and saw people trying to hold on to floating pieces of the boat, some grabbing onto each other. But most of them couldn’t swim. People were going under. Some were just floating, lifeless. Others were crying out for help.

“That moment… you could see death in people’s eyes. You could actually see it. It was tragic. The kind of thing that stays with you forever.”

But Jimmy swam.

He was from Delta State, a river boy. He had swum in rivers since he could walk. As a kid, he used to dive and catch fish. Back then, it was for fun. Now, it was survival.

Above, the sound of chopper blades sliced through the wind. Helicopters hovered, cameras flashing, lights scanning the water. At first, it wasn’t clear if they were rescuers or just observers, watching a human tragedy from the sky.

Jimmy kept swimming. Kept holding on.

Eventually, rescue boats arrived. Small, white vessels slicing through the wreckage of what used to be their dinghy. They began pulling people out of the water, one by one.

Jimmy couldn’t even remember how he was lifted into the boat. His last memory before blacking out was the feeling of someone’s hand grabbing his wrist and pulling.

That was the moment he knew he had made it across the sea and out of Libya.

Out of hell.

Arrival in Italy

By the time the rescue boats pulled Jimmy out of the water, he wasn’t even sure he was still alive. Not in the way that counted.

He couldn’t speak. Couldn’t cry. Couldn’t even remember his name. For three whole days, he and the others drifted in a strange silence, not at sea anymore, but not yet on solid ground, physically or mentally.

“We couldn’t talk,” he remembered. “We couldn’t say our names. We were just there. Just… broken. Some people were crying. Some were praying. But most of us? We were quiet. Completely quiet. Because what words do you have left after watching people drown next to you?”

When his voice finally returned, he was in Pescara, Italy. A quiet city on the Adriatic coast, not far from the sea that almost killed him. That was where the system picked him up.

He was processed, tagged, and taken to a migrant camp, a new kind of confinement. No chains or beatings. But still, not freedom. Not really.

The Italians didn’t jail him. Instead, he was placed under the European Union’s migrant resettlement protocol. That meant camp after camp, forms and fingerprints, interviews and silence, a waiting game that could stretch into five, six, ten, even fifteen years depending on the country and the case.

“They don’t arrest you,” Jimmy explained. “But they don’t let you live either. They just put you in a place, away from everyone, and you wait. That’s it. You wait for someone to decide if you deserve to stay.”

He was 17 years old. And once again, he was in a system that didn’t know what to do with him.

The camps were tucked far from the cities, deep in rural Italian villages where locals barely interacted with foreigners. There was no school. No work. No future. Just time. Endless, bitter time.

The government said it was for their protection and society’s. They claimed the migrants needed to be evaluated mentally. That, after surviving war and torture, they might be unstable. Dangerous, even. So instead of help, they got isolation.

“They looked at us like we were broken,” Jimmy said. “Like we were bombs waiting to explode.”

Psychiatrists and psychologists were sent in to interview them. To evaluate and observe. But even they couldn’t handle what they heard.

“I told them everything. About the desert. The torture. How I was chained up, hung from ceilings, beaten with pipes. How I drank my own urine to survive. I watched one therapist cry in front of me. Then she walked out. She never came back.”

Many others did the same. One after another, therapists and case workers began quitting. Not because they didn’t care. But because they couldn’t take it.

“They said they couldn’t help people like us,” he said quietly. “They thought we were too far gone.”

Language teachers came and went. Locals looked at them with suspicion. They were warned not to greet anyone in the streets. Not to talk, not to linger. Just exist, quietly, invisibly.

Yes, there was food. Three times a day. Yes, there were clothes and shelter. Basic medical care. But none of it felt like compassion. It felt like containment.

“They treated our wounds,” Jimmy admitted. “They gave us drugs, took us to the hospital, helped us call home. But it wasn’t free. Nothing was free. The European Union paid for everything. And every African country had to contribute to the cost of taking care of their own citizens. That’s what we were: an expense. A number on a ledger.”

He stayed in that limbo for almost four years.

Nine months in, he was called to court for his first asylum presentation. A formal interview where he had to explain to a panel of judges, social workers, and mental health experts why he should be allowed to stay, why they shouldn’t send him back to Nigeria, why they shouldn’t erase the last four years of his suffering.

He laid it all out. Everything. The desert. The chains. The saltwater. The screams. The ghetto. The fire.

“I told them everything,” he said. “All of it. I didn’t leave out a single detail. I thought if they knew what I had been through, they’d understand.”

They listened. Then they said no.

What happens next? Did Jimmy make it? Find out in part 8 of Jimmy’s story next Friday, only on Pulse.ng