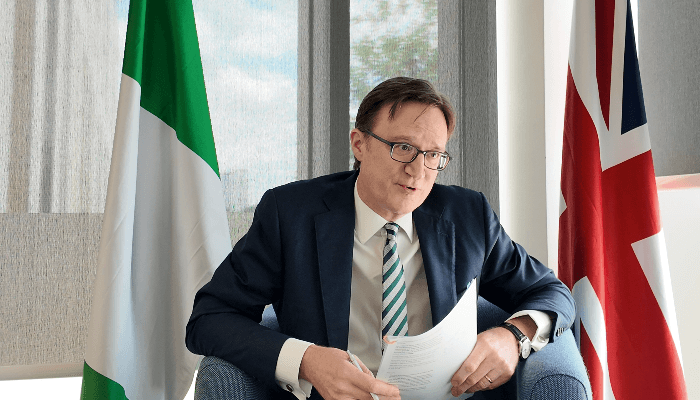

Tinubu’s reforms spark stronger UK trade-Nigeria trade, investment ties – Montgomery, British High Commissioner

By Onyinye Nwachukwu

Copyright businessday

The United Kingdom has described its economic partnership with Nigeria as “stronger than ever,” with bilateral trade hitting a record £7.9 billion (₦16 trillion), as British investors respond to Nigeria’s sweeping economic reforms. Richard Montgomery, British High Commissioner says this surge reflects renewed confidence in Nigeria’s direction and signals a turning point in UK-Nigeria relations. He highlights the Enhanced Trade and Investment Partnership (ETIP), signed in 2024, as a catalyst for deeper collaboration in key sectors such as technology, creative industries, agriculture, clean energy, healthcare, and finance. Montgomery notes that British companies are now moving “from talk to transactions,” with growing interest in Nigeria’s fast-evolving tech scene and agribusiness potential. The focus, he says, is firmly on delivering real deals that create jobs and shared growth. A seasoned diplomat and development expert, Montgomery previously served as the UK Executive Director at the World Bank in Washington (2018–2022). At the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), he held several senior positions — including Director for Asia, the Caribbean & Overseas Territories, and Country Director in both Nigeria (2009–2013) and Pakistan. He has also held postings in India, Bangladesh, and Zambia. In this exclusive interview with BusinessDay’s Onyinye Nwachukwu, Abuja Bureau Chief, and Ojochenemi Onje, Foreign Affairs Correspondent, Montgomery explains why the UK is doubling down on Nigeria’s reform momentum — and what comes next for both countries.

QUE: UK-Nigeria relationship has spanned many years, with both countries regarded as important partners. Can you walk us through where things stand today, particularly in terms of trade, bilateral cooperation, and the new areas of collaboration that are being prioritised?

First, you’re absolutely right we have such a long history. Before I come to trade, let me talk about the broader relationship. I think it’s in really good shape at the moment, and that’s because both our governments are now working much more closely together than in recent years. We saw an elevation in our relationship in November last year when our former Foreign Secretary, now Deputy Prime Minister David Lammy, came to Nigeria. It was the first country he visited on the continent as Foreign Secretary. He met with the President, Bola Tinubu and Yusuf Tuggar, Minister of Foreign Affairs and together they signed a strategic partnership. That agreement, which is available online, outlines the broad areas of collaboration we’ve committed to deepening. These include mutual growth, which I’ll come back to in a moment, as well as security and defence, migration and home affairs, including our visa relationship, development cooperation, foreign policy dialogue, and of course, people-to-people links. That elevation of the bilateral relationship has created a framework we’ve been building on since November, and across each of these pillars we are taking forward new initiatives, one of which directly relates to your question about trade. Under the pillar of mutual growth, our goal is to create jobs and foster economic expansion in both our countries. In fact, both countries are currently undertaking significant economic reforms to achieve exactly that.

At the heart of this mutual growth agenda is the Enhanced Trade and Investment Partnership, which structures our trade dialogue. It’s a very important framework, and you can also find it online. It identifies, through a mutually negotiated process, seven or eight priority areas where the UK and Nigeria have agreed to collaborate. These sectors include financial services, new technology, the creative economy, higher education, clean energy, agriculture, and life sciences such as health. In each of these areas, we are developing dialogue that focuses on policies, regulations, and standards, making sure our institutions work effectively together as well as pushing to get specific deals across the line. These are deals designed to generate growth in both countries and to strengthen trade and investment, particularly between the UK and Nigeria. I’m especially delighted that UK-Nigeria trade is now at its highest level ever. The latest figures, up to the end of July, show trade between us at £7.9 billion, which is about $10.7 billion or ₦16 trillion. That’s a significant figure, and I believe the increase in trade volumes is partly being driven by the economic reforms currently underway in Nigeria.

QUE: Is that trade figure annually?

That’s an annual figure. We’re seeing a major shift in the level of cooperation between our two governments on trade and investment. There is new work happening in priority sectors where the UK has a comparative advantage and which align closely with Nigeria’s growth plans. We’re also seeing our trade figures rise as a result. I’d add that Nigerian businesses are now making greater use of the City of London than in the past, tapping into UK capital markets in ways that are driving higher investment rates in Nigeria. So, across the board, the indicators for trade and investment between the two countries are moving upward, and it’s a very positive picture. I’d be happy to talk about any specific aspect you’d like to explore further.

QUE: Trade between Nigeria and the UK is clearly on the rise, driven by economic reforms that Nigerians find challenging, but which the UK views as essential. How do you assess these reforms, and in what ways have they contributed to strengthening trade relations between the two countries?

You referenced that reforms are difficult, and I recognise that some of these reforms are very painful for ordinary people. Many Nigerians I meet talk about how the depreciation of the Naira and inflation have really hit the cost of living, and I understand just how tough that is. Still, there isn’t an alternative if Nigeria wants to get onto a higher growth path that creates better jobs and higher incomes in the future. To put this in perspective: for the last ten years, Nigeria’s economic growth has averaged about 2%, while the population has been growing at 5%. That means real incomes will keep falling unless the country gets onto a higher growth trajectory. So yes, in the short term, these reforms are painful, and I hear that everywhere I go. But if the goal is better incomes and livelihoods for future generations, there really is no alternative. I do believe the reforms are beginning to work. I’m a great admirer of the leadership being shown by His Excellency the President, Wale Edun, Minister of Finance, Yemi Cardoso, Governor of Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and several other ministers we work closely with. Whether it’s Jumoke Oduwole, Minister of Industry, Trade and Investment or Hannatu Musawa, Minister of Art, Culture, Tourism and Creative Economy or Bosun Tijani, Minister of Communications and Digital Economy, you have an impressive team of economic ministers driving progress at both the macroeconomic and sectoral levels.

We are starting to see major indicators that these reforms are taking hold. Inflation, for example, was above 30% last year but has now come down to 20%. That’s still too high, but the trend is in the right direction. This government inherited a very difficult economic legacy, but by abolishing the fuel subsidy and improving tax collection, fiscal management is now much stronger. Allocations to public services have increased significantly. Federal allocations to the states are up by 90% in just two years. Yes, with the Naira’s depreciation the real value is less than that headline figure, but even so, states are receiving 40–50% more than before, allowing for greater investment in public services and infrastructure. We’ve also seen the Naira stabilise. While there has been depreciation, the relative stability over the last five to six months has been impressive. That gives investors confidence, they can now plan, knowing that the exchange rate won’t swing unpredictably. The CBN is also managing monetary policy more effectively, with reserves rising from three months’ import cover to twelve months. Nigeria now has about $41 billion in reserves. Even the IMF, which has long been skeptical about Nigeria, released a very positive Article IV report earlier this year. That’s a recognition of the progress being made. I regularly ask Minister Edun and Governor Cardoso how the UK can best support them in their negotiations with the international financial institutions and the City of London. The feedback from the IMF and World Bank over the last six months has been much more positive, and that is to their credit.

What really matters, however, is whether these reforms unlock investment. And we’re starting to see that too. Credit rating agencies have upgraded Nigeria, which is a good sign. Just last week I met with two groups of City of London investors, and they were clearly optimistic. They see new opportunities in Nigeria. British businesses are also taking more interest. In July, the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, led a delegation of 27 tech companies to Lagos, seeking Nigerian partners. Nigeria has a vibrant tech cluster with innovation and talent, and its role as a gateway to West African markets makes it particularly attractive. Just as the UK serves as a gateway for Nigerian companies to global markets, Nigeria is positioning itself as the entry point into the sub region. Some of those 27 companies are already moving ahead with new investments, for instance, Tech1M, a digital HR platform that uses AI to help companies manage their workforce more efficiently, is setting up operations here.

There is also a surge of collaboration in the creative industries. We are hoping to finalise a number of co-production deals in film and music. I’m especially delighted about Mo Abudu, the remarkable woman behind EbonyLife in Lagos. She is planning to establish EbonyLife London by the end of the year, with the aim of building a platform that allows Nigerian creative companies to tap into the UK’s massive creative economy. To put that in context, the UK creative sector employs 2.4 million people and is a gateway for music, film, digital content, and fashion. The potential synergy with Nigeria’s fast-growing creative sector is enormous. And then there is the Nigerian diaspora in the UK, which acts as a living bridge. They understand how both Nigeria and London work, and they are uniquely placed to connect opportunities between the two countries.

QUE: You’ve mentioned growing interest from UK business leaders in Nigeria. Would you say this is translating more into foreign direct investment or portfolio flows?

I think recently there’s been more short-term money, bond lending. One of the roundtables I had last week was with those types of investors, and they recognised that in the next phase of Nigeria’s growth, it will need less of that type of money. They are going to have to shift to equity and long-term loan instruments. I think that’s an interesting recognition that the reforms are now creating more investment opportunities in Nigeria, and that the Ministry of Finance is managing its debt well, which means it won’t need so much short-term money. I used to work at the World Bank, so I used to pore over IMF reports and so forth, I could bore you for longer on this issue, but I do think there is a shift happening whereby we’re going to move from short- to longer-term money. And the UK government is trying to do that. I can go into details, but we have a development finance institution, British International Investment. It has a big portfolio in Nigeria, about £700 million, heading up for a billion dollars, mainly long-term loans and equity. It is investing in Nigerian agricultural companies that are exporting cocoa and cashew. It’s also helping several Nigerian banks create mechanisms to lend more to small and medium enterprises, which are a big employment sector for Nigeria. So we’re trying to capitalise and show that there are economic opportunities in Nigeria to attract bigger-scale finance in the future.

QUE: With global aid declining, Nigeria’s priority is clearly attracting investment over traditional assistance. That said, aid still has its place when available. Are there specific areas where the UK is looking to provide support moving forward, and have any discussions been held around this?

The short answer is yes. But let me start where you began. Nigeria needs both foreign investment and domestic investment from the commercial banking sector and from international investors. The role of aid in a large country like Nigeria is relatively small. The last time I checked, aid accounted for only about 1 to 2% of GDP, and most of that comes from big financing institutions like the World Bank or the African Development Bank, where Nigeria is a shareholder. As a member, Nigeria is entitled to access those very low-cost loans, and it should take advantage of them as much as possible. Our aid contributions are also dwarfed by Nigeria’s domestic resources. Federal and state budgets combined come to about $55 billion a year, whereas aid might total $1, 2, maybe $3 or $4 billion in a good year, depending on disbursements from the banks. So I fully agree, Nigeria doesn’t need traditional aid. The UK, and my new ministers in particular, have been very clear: while Nigeria remains a priority for our official development assistance, what we need to do is move away from direct project funding, direct health or education initiatives and shift towards supporting government reforms and building national systems. Let me give three examples. First, we are very interested in supporting health reforms under Mohammed Pate, Minister of Health and Social Welfare, where impressive changes are already underway. Second, we are financing expertise and knowledge-sharing in education with Minister of Education, another strong partner. And third, we are supporting government effectiveness by providing expertise to the Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation and the Office of the Head of Civil Service, helping them draw on international experience to make government delivery and the civil service more effective, adopting, adapting, or rejecting approaches as Nigerian leadership sees fit.

I want to return to the starting point: mutual growth is our top priority. Yes, we cooperate on security and defence, but growth is the foundation for stronger livelihoods and a stronger Nigeria and indeed for the UK too. Much of our work is shifting in that direction. We’re reallocating resources, both within the High Commission and in our official development assistance towards activities that support mutual growth. Sometimes that’s at the policy level. I feel privileged to be here on a second posting. In my first posting, Yemi Cardoso was chair of Citibank, and Wale Edun was serving in the Lagos State government. Many UK diplomats have also served multiple postings in Nigeria, so these are not just diplomatic conversations, we have relationships and friendships that allow deeper cooperation. The Central Bank of Nigeria, for instance, seeks a peer relationship with the Bank of England. The Federal Inland Revenue Service looks to His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs to learn about tax collection and data systems. In our small way, when asked, we use our official development assistance to bring in experts who can share UK experience, leaving Nigeria free to adapt, adopt, or reject as it wishes. These relationships help us support, in our own way, the economic reforms that create a stronger investment environment, not only for British businesses but for others as well. Through our Enhanced Trade and Investment Partnership, we’re also backing initiatives across five or six key sectors where we believe investment can be attracted and jobs created. So yes, we are working on Nigeria’s economic growth agenda at several levels, and part of that is financed by official development assistance. But this is not aid in the sense of charity, Nigeria doesn’t want that, and neither do we. Nigeria doesn’t want donors; it wants partners and investors. And that’s exactly what the UK government wants to be.

QUE: In your view, is Nigeria’s approach to tax reform headed in the right direction?

QUE: Is the UK actively involved in supporting that reform process?

I think much of the credit goes to Taiwo Oyedele, Chairman, Presidential Committee on Fiscal Policy and Tax Reforms in Nigeria and Zacch Adedeji, Executive Chairman, Federal Inland Revenue Service, with whom me and my technical experts here, have had extensive conversations. In a small way, when invited, we’ve provided comparative expertise and support. For instance, Zacch Adedeji was very interested in how His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) collects taxpayer data, which is essential for ensuring the right amount of tax is collected. We’ve observed a significant rise in revenue collection in Nigeria, not because tax rates have been increased, but because the Federal Inland Revenue Service has found more efficient ways to collect taxes. You asked whether we agree with the tax reforms of course, there are aspects that reflect political compromises negotiated through the National Assembly. That is the sovereign right of every country. We have similar debates about tax in the UK, and rightly so, between Parliament and the executive. Overall, however, we are very impressed with the reforms. They represent a major step forward in simplifying the tax burden on businesses by consolidating taxes and making the relationship between taxpayers and collection agencies more direct. One of the longstanding challenges businesses face here is unofficial payments to various agencies, unpredictable costs that are difficult to plan for and impose additional burdens. The reforms, we believe, will make the system more predictable and business-friendly, creating a stronger foundation for attracting investment.

QUE: Given the progress with ongoing reforms, are there deliberate efforts underway to attract more UK businesses to invest in Nigeria? And secondly, how would you assess the current state of Nigeria’s business environment, particularly from the perspective of UK investors?

I think the biggest opportunities lie in the creative economy, co-production, and the technology sector, where we’ve seen a steady stream of UK businesses coming to Lagos and attending GITEX. This has been complemented by Nigerian tech companies participating in the UK Tech Week a few months ago. So, creative technology is one area of real growth. British universities are also recognising that they cannot rely solely on Nigerian students traveling to the UK, given the costs involved. Many are now exploring how to establish a presence in Nigeria. We’ve already seen elite schools like Charterhouse and Rugby School set up in Lagos, but I believe the bigger trend to watch will be major UK universities forming partnerships with Nigerian institutions to establish a stronger local presence. Alongside technology and higher education, agriculture remains a priority sector. Nearly all of Nigeria’s non-oil exports come from just four areas: cocoa, cashews, sesame, and fertiliser. Cocoa alone accounts for 40% of non-oil exports. While the potential in agriculture is enormous, it is also the most challenging sector. Issues such as poor storage, lack of cold chain infrastructure, and limited access to finance result in Nigeria losing about 40% of its harvest. That said, we are working at several levels. At the farmer level, for instance, the PropCon Plus project is supporting four million farmers through small but impactful interventions such as vaccinating poultry to reduce mortality rates, providing inputs like fertiliser, and creating commercial pathways for smallholders. Recently, one of these innovations led to a major investment: Babban Gona, a company that aggregates produce, packages it, and exports to global markets, secured a $7.5 million investment from British International Investment. This will enable the company to expand its reach and support thousands more farmers. At a higher level, we are focused on strengthening standards and regulatory institutions. Through the UK’s Developing Countries Trading Scheme, 3,000 Nigerian agricultural products already enter the UK tariff-free, the challenge is not tariffs but meeting export standards, improving packaging, and ensuring quick transportation. Overcoming these barriers will unlock agricultural exports, create jobs, and improve livelihoods.

QUE: Agricultural export rejects from Nigeria remain high. Have there been any discussions with Nigerian authorities on improving standards and reducing these rejections?

That’s part of the Enhanced Trade and Investment Partnership. And one of the organisations we’re working with is the Nigerian Standards Organisation, along with others like the Nigerian Customs Service. We need to make it easier for exporters not only to get certification but also to get their goods through the ports. Some of the major infrastructure being developed to address bottlenecks at the ports is going to be very important, and we’re following that government-led investment very closely.

British International Investment (BII) is another example. It has invested in Johnvents Cocoa and in Valency International. These are two companies already exporting, cocoa in the case of Johnvents, and cashew nuts in the case of Valency International. Where we find companies that have established export channels to the UK, like these two, we are trying to put more money into them through our development finance institution. We hope this has a demonstration effect. So, if someone wants to seize the opportunity to export cocoa or cashews, my advice is: go and talk to those companies that are already doing it, because there is enormous potential to scale up.

QUE: Recent changes to UK immigration rules — particularly restrictions on dependents for international students and adjustments to salary thresholds for skilled workers — have sparked concern in Nigeria, where the UK remains a top destination for education and migration. How does the High Commission respond to perceptions that these policies disproportionately affect Nigerian applicants, and what assurances can you offer to maintain strong people-to-people ties between both countries?

That’s not true. The rules are transparent and applicable to all countries. There’s nothing about Nigeria in particular. A really important point to keep emphasising is that Nigeria has consistently been the third or fourth largest recipient of new UK visas over the last several years. The top two countries in terms of visa grants are, of course, China and India, simply because they are so large, together they have about two and a half billion people. Nigeria is in close rivalry with Pakistan for the third slot. And our visa relationship with Nigeria is absolutely huge. When I first arrived, it was 325,000 visas a year. Last year, it was 260,000 new visas. And, of course, many Nigerians already hold five- or ten-year visas. So this is a very substantial relationship. I shouldn’t comment on other countries’ relationships, but our visa numbers with Nigeria are so far ahead of any other country that Nigeria has diplomatic relations with, ahead of even all 27 European Union countries combined, and ahead of any other major country you might care to name. That’s how significant this visa relationship is. Yes, there have been changes in the rules, such as restrictions on dependents for student visas, recent adjustments in work visa rules, and likely future changes as well. But these changes are not about restricting any particular nationality. We have to manage legal migration in a way that suits the needs of the UK economy, where there are job opportunities, where we need skills, talent, and workers. There was a recent UK White Paper on immigration, which you may have seen. In 2023–24, the UK admitted 1.6 million new long-term immigrants, into a country with a population of about 67 million. Immigration in the last eight to ten years has therefore been huge, and it must be managed in a way that makes sense for both our economy and our politics. This is because, as we all know, a particularly live issue in British politics at the moment is illegal migration. This has caused deep concern among the British public. Illegal migration unfortunately comes from various directions, and in Nigeria we have seen an increase in false documents and illegitimate visa applications. But having said that, the success rates for Nigerians are very high. Ninety-five percent of people who apply for a study visa to the UK are successful. Seventy percent of those applying for a work visa are successful. And over 60 percent of those applying for a visit visa are successful. These are very strong approval rates, showing that Nigerian applicants continue to do very well.

QUE: What specific talents or skills does the UK typically look for when considering visa application with Nigerian professionals or students?

We have this huge growth happening in some of the sectors that I’ve been talking about earlier, creatives and technology. I saw this morning that Microsoft is investing 30 billion dollars over the next four years in technology infrastructure to power the artificial intelligence and digital revolution. Google has also announced 7 billion dollars over the next two years. That’s 37 billion dollars announced during the state visit of President Trump to the UK. And I think, even I’m a bit surprised to see all these deals come through in what is a huge investment. It really shows that the UK technology cluster is going to boom. What I would say to Nigerian counterparts and friends is this: there are going to be opportunities in the UK tech ecosystem because of this massive investment. So let’s start talking about how we can work together.

QUE: Are you currently collaborating with Minister Bosun Tijani, and if so, in which specific areas?

I first met Bosun Tijani when he set up Co-Creation Hub in Lagos during my first posting in about 2010. I was bowled over then by all the tech talent he had mobilised around that. So yes, we do talk to him. He’s a very busy man, and I wouldn’t be presumptuous in my relationship with the Honourable Minister. But we’re very respectful, and he’s very engaged in these issues. In fact, he was the only minister from outside the G7 invited to the Artificial Intelligence Summit under the previous government led by Prime Minister Rishi Sunak. Bosun Tijani was recognised as someone we needed to have in the room, not only as a voice for Africa but also for middle-ground economies.

QUE: With persistent security challenges in Nigeria ranging from terrorism in the Northeast to rising incidents of banditry and kidnapping, how is the UK supporting Nigeria’s security architecture—both in terms of intelligence cooperation and capacity building? Also, are there talks or concrete actions on how the UK can help promote peace in the Sahel?

First of all, my heart goes out to anybody that has had a kidnapping case in their family or extended family. We have colleagues in the British High Commission who have family members who have experienced these very awful situations. And it’s worse in some parts of the country than others. I’m sure you know we have a security and defence partnership as part of the strategic partnership, though it existed beforehand. We have quite a long track record of collaboration between our armed forces. We share quite a lot of traditions and approaches to training. We just had our recent security and defence partnership talks, the annual talks, in July in London. They happen under the auspices of our national security advisors, Jonathan Powell in the UK and Nuhu Ribadu in Nigeria. The technical talks this year were co-chaired on the Nigerian side by Muhammed Abubakar, Minister of Defence and indeed, we’ve just hosted Christopher Musa, Nigeria’s Chief of Defence Staff in the UK as well. We always agree an annual plan, and some of this involves practical support. We help train Nigerian troops heading to the front line in the northeast, which is the epicenter of the terrorist threat and conflict. Tragically, too many people are being killed by terrorists using improvised explosive devices. One of the practical things we do is train troops going into the northeast on how to spot IEDs, how to respond to different types, and how to defuse them. We also provide technical support, including a recent donation of about half a million dollars’ worth of equipment to the Maiduguri counter-IED coordination cell.

Armed forces must always review what types of IEDs are being used, identify the signatures of bomb makers, and determine how best to deal with different devices. Intelligence-led operations are vital to counter IEDs effectively. All of this is partial, of course, and we greatly admire the scale of challenges Nigeria’s armed forces are facing. In our small way, we provide this type of technical training. For example, I won’t go into details, but the security and defence talks agreed another round of new training programmes that are of interest to the Nigerian armed forces. Nigeria will seek its security partnerships from a range of partners, but the UK armed forces bring experience from many difficult theatres over the last two decades which include Iraq, Afghanistan, and others. We have lessons to share, but we also want to engage in dialogue and learn from Nigerian security partners about some of the complex coordination issues in counterterrorism operations. In our small way, we’ve also tried to support the Multinational Joint Task Force. We have shared our experience of civilian-military coordination, whether in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Northern Ireland. And we’ve learned many lessons from working with governors in the Northeast, Babagana Zulum, Governor of Borno State and others and with area commanders on military-civilian cooperation.

You started with a question on kidnapping, and here too we have shared lessons via our National Crime Agency on how different parts of the UK government respond when a kidnapping happens. We have helped the Office of the National Security Adviser set up a multi-agency anti-kidnap cell, which I visited a couple of months ago. They are tracking kidnapping cases across the country and identifying patterns that allow them to provide intelligence to help secure releases. This work requires the involvement of police, state governments, the military, and security agencies, everyone must share information and work together to resolve cases. I think you have seen ONSA recently announce several group and individual releases of kidnapped persons. Some of those results are coming out of the ONSA anti-kidnap fusion cell, which has benefited from the support of our UK government experts.

QUE: In your view, is Nigeria doing enough to address its security challenges?

I think Nigeria faces an over-the-horizon threat from instability in the Sahel. And part of that is caused by the tragic situation in Sudan, which is a civil war with no real end in sight. And that will have spillover effects into the northeast Lake Chad conflict zone. And I think Nigeria is very aware of the over-horizon risk coming from Russian interference in the Sahel, whether it’s disinformation or the private military companies. I don’t think that what used to be called bargainers, now Africa Corp, is going to be any more successful than anybody else in countering the terrorist groups in Mali and Niger. And, I’m delighted that Nigeria, and indeed the UK and other partners, really want to have more collaboration with Niger and Mali and Burkina Faso, if they will allow us. I think those challenges are real and I don’t think the Russian presence is going to be helpful in the medium term. I think Nigeria is acutely aware of that, and we’re very appreciative that Nigeria has been reaching out constructively to the alliance of Sahelian states and is approaching these issues pragmatically. There is still good dialogue between the militaries of Nigeria and Niger, for example. That’s very important because there are going to be spillover effects into Nigeria if the situation isn’t managed better in the region. So we are concerned about it, but we’ve seen a lot of progress and we have a very constructive relationship with the Office of National Security, with your Chief of Defence staff and heads of services and other agencies. We don’t underestimate the challenges, but we’re very admiring of the steps taken by the agencies in the last two years to tackle some of these issues.

QUE: What additional steps do you believe could strengthen Nigeria’s response to its security challenges?

You’re asking a very pointed question. I think these are sorts of issues that are big challenges, and I have a lot of confidence in the present leadership of Nigeria’s security architecture to find the best way through. Our job is not to say what we think can be done. I mean, outsiders can never know what the best strategy and tactics are. But when we’re invited by Nigerian partners to help on a specific issue, we’re very keen to do so. So on the anti-kidnap cell or the counter-IED, these were specific requests where, in conversation and dialogue through the Security and Defence Partnership, it was clear that they were looking for new ideas. We had some experience that they would want to understand, to either adapt, adopt, or reject. Those are good examples where it’s Nigerian leadership that has come forward and said, “Have you got anything that is of use to us here?” And we’ve developed initiatives. We’re very open to those types of approaches in the future, and our annual dialogue enables us to have that regular planning process.