By Cloe Read

Copyright brisbanetimes

At times, the 18-year-old appeared to cry. As the court adjourned in the middle of the day, his parents waited anxiously in the arrest court foyer, his father pacing.

Just after 6pm, as their son was released, the Belters pulled their car around to the closest available space to the door as television reporters went live for their evening bulletins.

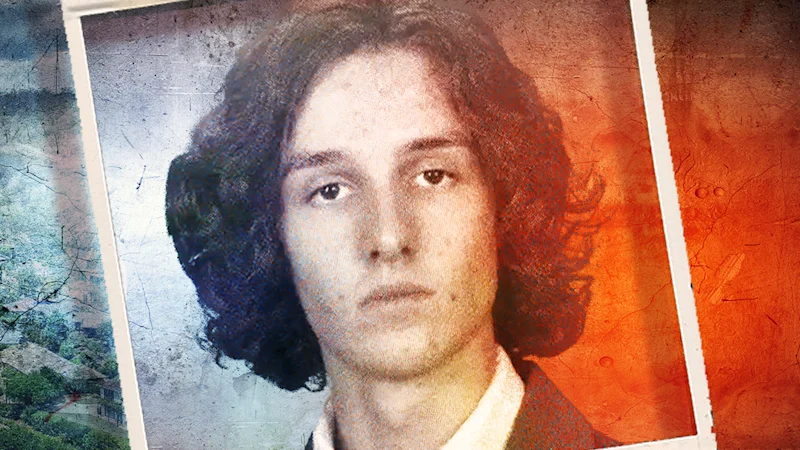

The boy was peppered by journalists: was he a teen terrorist? He covered his face with his jumper, despite his yearbook photos having been splashed across the news for hours.

When he got in the car, he let the jumper fall away and stared absently out the window at the flashing of media cameras.

Other families have been known to leave their loved ones to walk from the watchhouse alone.

Hardy says Belter’s case shows how radicalisation could be allegedly infiltrating seemingly supportive homes.

The criminology associate professor stresses radicalisation is usually influenced by factors in someone’s personal life pushing someone towards violent content, such as a family death or a divorce.

He says the risks of the online environment alone could be overstated. “I do think human influence from somebody else who might have more criminal networks is often important to it.”

But he says far-right groups have also become advanced at exploiting young people through the use of humour and memes that were not necessarily as overtly problematic as videos of beheadings.

“You can imagine a 12-year-old looking at a meme that you know has some hidden message about Jewish people, and they don’t fully appreciate the meaning of that, but they laugh at the superficial humour, and share it with their friends,” Hardy says.

He likens radicalisation to when child soldiers are handed a firearm for the first time: a transforming moment where they experience power in a way they never felt before.

“There are all these psychological dynamics that go on that are not just about ideology,” he says.

‘You can imagine a 12-year-old looking at a meme that you know has some hidden message … they laugh at the superficial humour, and share it with their friends.’Keiran Hardy, Griffith University

Hardy says the ideological material police seized from Belter’s home was allegedly predominantly far right and neo-Nazi, but the ISIS video could have fulfilled an “instructional” role on how to kill. In far-right groups, those types of videos, Hardy says, play a role both as practical and instructional, but also act as psychological preparation.

Belter’s case is one of many Australian authorities are working to investigate. And the Australian Security Intelligence Operation says they’re noticing younger people radicalising earlier in life.

ASIO Director General of Security Mike Burgess claimed earlier this year that Australia had never faced so many different threats at scale at once, with the war in the Middle East exacerbating division, undermining social cohesion, and making acts of politically motivated violence more likely.

Distinctions between extremist motivations were also breaking down, with individuals cherry-picking antithetical ideologies to create hybrid beliefs.

He recalled one individual being motivated by Islamic State propaganda and neo-Nazi propaganda, and another allegedly described himself as a left-wing environmentalist aligned with Hitler.

The AFP urges parents to be aware of who their children are communicating with online.

Between 2020 and 2024, the AFP and state authorities investigated 37 children aged 17 or younger. The youngest was 12. More than half of those children were charged with a Commonwealth or state offence.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.