While the influx of tourists has brought economic opportunities, it has also raised tensions with local residents, who face disruptions to their daily lives. The challenge now lies in balancing the benefits of tourism with the preservation of community life.

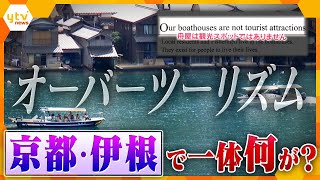

Located more than two hours by car from central Kyoto, Ine has a population of roughly 1,800. The town’s distinctive waterfront houses, known as funaya, have long been its symbol, with sightseeing boats offering views of the rows of homes from the sea. After the COVID-19 pandemic, these scenes went viral on social media, and the number of restaurants and shops increased. In fiscal 2024, Ine welcomed around 480,000 visitors, the highest figure on record.

Yet the narrow streets of Ine, some barely wide enough for pedestrians to extend their arms, have struggled to cope with the surge in traffic. Tourists’ cars frequently clog the roads, creating dangerous situations in cramped alleyways. Residents report that tourists often trespass onto private property, sometimes eating or drinking in their yards. For fishermen, who rise early and need rest during the day, the constant activity has made it difficult to relax. “I can’t live peacefully anymore,” one resident said, recalling how strangers rolled their suitcases to his front door and spoke loudly in front of his home.

While some locals lament the disruption, others see tourism as a lifeline. Ine’s population has halved over the past 35 years, and the town has faced economic decline. Residents note that tourism has spurred the reopening of shops, created jobs, and drawn back younger people to work in the community. “It has become livelier,” one resident said, noting the increase in young business owners.

Still, measures to handle the influx remain limited. Parking lots and traffic control staff have been introduced, but space and resources are constrained. About a decade ago, the town invested in a multipurpose facility to provide entertainment and workplaces for visitors and returning young people, in an effort to combine community needs with tourism. Yet local officials acknowledge that Ine was “never originally a tourist destination” and ask for residents’ patience.

The town’s tourism association has begun distributing leaflets to visitors, reminding them that “boat houses are not tourist attractions” and urging them not to enter private homes. The campaign stresses that Ine is a living community, not an open-air museum. “We want visitors to understand that people live here, and to enjoy Ine while respecting that,” said one organizer.

For Ine, tourism is both a blessing and a burden—vital for sustaining its shrinking community, yet disruptive to its fragile way of life. With nearly half a million people now arriving each year, the town’s future depends on finding ways for visitors and residents to coexist.

Source: YOMIURI