Penn’s CAR-T pioneer Carl June won two awards in the last month. His work is far from finished.

Philadelphia’s pioneering cancer scientist, Carl June, has been honored with two awards in the last month for his seminal work engineering the body’s immune system to fight cancer.

June has spent decades researching CAR-T, an immunotherapy in which regular immune cells are genetically modified to become cancer-killing super soldiers. And he says his lab’s work is far from finished.

The University of Pennsylvania scientist was chosen last week for the inaugural Broermann Medical Innovation Award for his decades of research on chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy, known as CAR-T. Touted as “a living drug,” the therapy has revolutionized treatment for blood cancers, saving tens of thousands of lives since its first use in a 2010 clinical trial June co-led at Penn.

The treatment used in that trial, Kymriah, was developed in June’s lab and ultimately became the first CAR-T cell therapy to gain FDA approval in 2017.

He will share the award, worth more than $1 million, with Columbia University scientist Michel Sadelain, who worked on a similar technique at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Since June’s clinical success, several other CAR-T products have been approved, and more than 1,000 trials have been launched around the world. Interest in cell and gene therapies has also exploded throughout Philadelphia, turning the city into a biotech hub that some have nicknamed “Cellicon Valley.”

The Penn scientist has collected a number of prestigious honors over the years, including a 2023 Breakthrough Prize and, earlier this month, a 2025 Balzan Prize for Gene and Gene-Modified Cell Therapy. While most of these recognize June’s early successes in developing CAR-T, his lab has continued making advances in the lab and clinic.

Their recent efforts have involved optimizing the therapy and expanding its uses to other cancers and diseases. The Inquirer spoke with June, who has been at Penn since 1999, to learn more about his lab’s latest research and the future of CAR-T.

The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What has your lab been up to recently?

What we’re focusing on in my lab is figuring out what it will take to cure solid cancers. There’s still a lot of work needed in blood cancers, but I think that’s more of an engineering problem. It’s getting the right targets.

I’m confident that T cells can kill every blood cancer if they’re properly targeted. We may need to combine it with other things, but we’re not anywhere close to that for solid cancers like pancreatic cancer. We know in principle what we can do to tackle solid cancers, but we still need a lot of science to be uncovered to make it reproducible.

We just had a paper published a few weeks ago where we used CAR-T cells for pancreatic cancer, and we found out that the CAR-T cells in the patients were completely exhausted within two weeks. They just stopped working. That doesn’t happen in blood cancer, so we’re studying the mechanisms of what makes that happen and what we can do to overcome that. That involves things like either genetic editing the T cells to knock out the molecules that allow exhaustion to happen, or overexpressing other molecules. That’s a very large area of research in my lab.

You found that these cells were only active for two weeks. How long are they usually active in blood cancers?

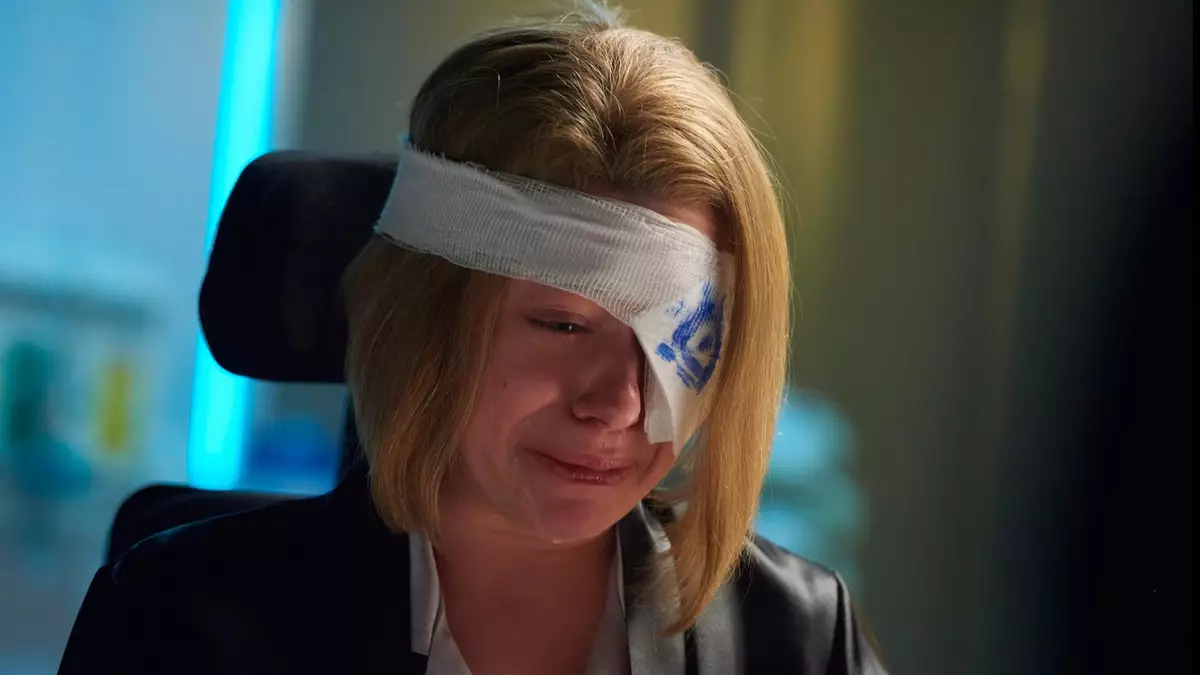

The first patient that we treated still has active CAR-T cells 10 years later. So we call them a living drug. And then Emily Whitehead, who’s a junior now at Penn, was seven years old basically when we treated her, and she still has CAR T cells. With blood cancer, a subset of patients have them pretty much indefinitely, and we haven’t seen that in solid cancer.

» READ MORE: Emily Whitehead, the first child cured of cancer with therapy from Penn, returns as a student.

In 2017, we made in mice CAR-T cells that we called “armored.” They secreted the cytokine interleukin 18 (IL18), which we showed, in mouse tumor models, made it much more potent. So then we started the trial in humans, and our first patients had complete responses. It was shocking. The T cells were basically 100 times more potent than what is currently FDA-approved.

How does IL18 boost the fighting abilities of these CAR-T cells?

One of the answers, for sure, is it activates the innate immune system, so things like natural killer cells and monocytes. We also think it can act as a growth factor for the CAR-T cells themselves. So it may have more than one mechanism of action. We still have ongoing trials looking at that here at Penn.

Are there other ways your lab is enhancing CAR-T cells?

We’re using screening strategies like CRISPR and base editing to screen for targets. We’ve identified many that right now are being tested in mice as ways to enhance the function of the T cells in a solid tumor.

We have one postdoc who could knock out 20 genes at one time. It’s amazing. That’s going to be an ongoing project, identifying ways to either prevent or slow down this exhaustion in solid tumors.

Autoimmunity was a huge surprise. Everyone was afraid that maybe there would be too many side effects with CAR cells in patients with autoimmunity. But two German professors, George Schett and Andreas Mackensen, did very careful studies in Germany over several years. They treated 15 patients with three different autoimmune diseases, and found a 100% response rate. It was extraordinary. They published it initially on one patient, a Vietnamese woman who has now been in remission for three years. She had lupus and got a single infusion of the CARs. They also treated scleroderma and myositis, these horrible autoimmune diseases.

I just taught a course two days ago at Penn where we looked on the government data website clinicaltrials.gov and there were 140 trials now in the world treating autoimmune disease with CAR cells. There are many more patients with autoimmune disease than there are cancer. And this is something we are looking at through both academic trials here at Penn and in the biotech/pharma industry.

Are there any applications of CAR-T from other groups that you really admire or that you find most promising?

Probably the most disappointing thing is how long it takes to go from preclinical experiments in animals to human results. It just takes too long. It’s a general problem we have.

But there’s exciting work with natural killer cells. And people at MD Anderson [in Texas] have been using umbilical cord blood, that would normally be thrown away when babies are born, to grow CAR cells. That’s exciting. It’s another approach rather than starting with peripheral blood from a cancer patient. And the advances with lipid nanoparticles and in vivo viral delivery have happened much faster than I thought it would.

I’m just astonished at how fast the field is moving forward.