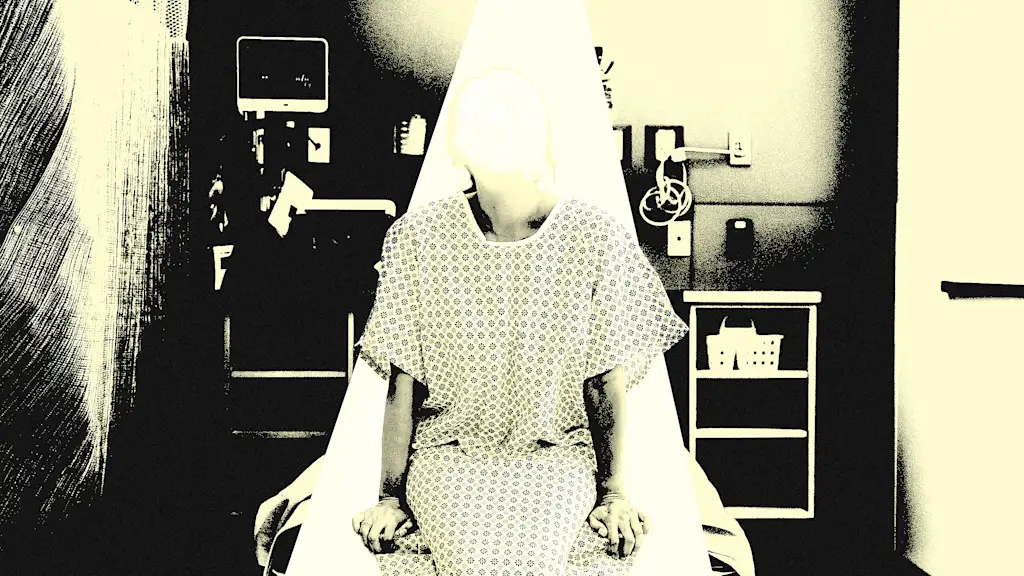

Women’s healthcare is under unprecedented attack. Women across the U.S. are being denied access to basic reproductive healthcare and funding for research into diseases that affect women is being cut.

There’s an urgent need for healthcare providers and, arguably, any brand that plays a role in women’s daily lives, to step up and transform women’s health services and spaces through feminist design.

Feminist design taps into women’s and under-represented group’s needs in order to create tools, services, and environments that combat systemic oppression. Propelled by the inequalities that surfaced over the COVID-19 pandemic, the current feminist movement is more intersectional and self-critical, shifting focus from the individual to large-scale change making. Feminist design champions equity for all.

Feminist design goes beyond adapting things to make them more accessible or friendly to women and girls. The goal with this approach is to make transformational change by questioning design as an entire system, by considering the systemic biases embedded in the design processes and asking ourselves what might be possible if these are challenged.

Subscribe to the Design newsletter.The latest innovations in design brought to you every weekday

Privacy Policy

|

Fast Company Newsletters

Design’s inherent gender bias

Like almost every industry, design has historically been shaped by patriarchal structures. With everything from smart phones to crash test dummies based on the requirements of the average male, women have been neglected by normative design. The Women in Global Health report found that during the pandemic only 14% of female healthcare workers had properly fitted PPE.

The industry continues to be male dominated; A survey by the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) in 2019 showed that women make up 61% of the design workforce but only 24% are in leadership roles.

The design of healthcare facilities is often rooted in hierarchical, paternalistic doctor–patient dynamics with environmental conditions that disfavor and often endanger women. For example, bright fluorescent lighting typical in hospitals has been found to increase stress levels and hinder the release of birthing hormones in laboring women.

By contrast, feminist design explores how sensorial design can reduce stress and improve overall well-being, and shifts the emphasis to care, listening, and shared decision-making. For example, well-being is integral to the design of the Pearl Tourville Women’s Pavilion in Charleston, South Carolina. The space was designed based on feedback from patients and staff, and features calming acoustics and aims to create a more welcoming, homelike atmosphere.

Likewise, the design of the Barlo MS Centre in Toronto, responds to the specific challenges experienced by the people it serves—patients with multiple sclerosis—and includes a customized gymnasium, high-tech lecture spaces, and an Activities of Daily Living Lab, where patients can learn how to modify their homes.

Women drive healthcare spending yet their needs are unmet

As well as the obvious health and societal benefits, there is a major economic case for feminist design. An investment of $350 million in women-focused research could generate an estimated $14 billion in economic returns by increasing productivity, reducing healthcare costs, and lessening the burden of disease, according to areport from Women’s Health Access Matters (WHAM).

Women make 80% of healthcare spending decisions, according to McKinsey & Company research, yet solutions tailored to their specific health needs remain underfunded. This provides a huge opportunity for brands, start-ups, and healthcare providers to deliver new value by transforming women’s health services, tech, and spaces.

advertisement

Principles of feminist design

Feminist design promotes reciprocal practices in which communities act as consultants, shaping decisions from the outset. There is no one-size-fits-all design solution: Every environment and its community is different. Problem-solving needs to be experimental and, above all, participatory. Ultimately the vision comes from within the community, and designers make the reality happen.

Here are some key ways to embed feminist design into products, services, platforms, buildings, and spaces:

1. Enable people to take ownership of their health and information

Empower women with knowledge and equip them with tools to improve their health at their own convenience. FOLX Health has done this for the LGBTQ+ community, as the first ever digital healthcare provider designed to meet the medical needs of this community, offering online consultations with medical experts and deliveries of treatments direct to people’s homes.

2. Provide comfortable and safe spaces

Understand the needs of diverse audiences and design flexible spaces to accommodate them, from family-centric areas with play spaces for children to intimate spaces for those breastfeeding or experiencing loss or trauma. Ensure basic facilities can be adjusted to accommodate different body types and abilities. Bring psychological comfort with soothing colour palettes, natural textures, and adjustable lighting.

Nature is vital—biophilic design principles can aid healing. Prioritize natural light, curved forms, and sensory stimuli. With its beautiful, yet functional, design, the Tokyo Toilet project is an example of how design can transform the most commonplace aspects of everyday life.

3. Build education programs and resources

Help women monitor their health, track symptoms, and make informed decisions through user-friendly interfaces and experiences. Inspire curiosity and exploration so people build a connected ecosystem of partners and information that’s expansive and accessible. This is showcased by Midi, a health platform for women over 40, where women can access virtual consultations with medical specialists trained in treating menopause symptoms.

4. Provide platforms for community voices

Inclusive language, accessibility, and privacy matter. From healthcare workers to patients and architects to policy makers, create a safe space for diverse groups to share their experiences, showing trust in their expertise. Foster a sense of belonging and establish a reciprocal feedback loop to drive strong relationships and open dialogue.

This approach informs women’s health research platform the Lowdown, which aims to enable women to review and research their health conditions, symptoms, and medications.

Designers as activists

Designers have the power to make real social impact by centering their work around empathy, care, and collaboration. The most transformative waves will come from those who dare to interrogate internal design processes and challenge convention.

Feminist practitioners, like pioneering architect Phyllis Birkby, have long resisted dominant power structures and imagined alternative futures. Their activism feels ever more urgent against today’s political backdrop.

Practices like experimental storytelling, community-building, education, and radical testing offer ways to reimagine how we live, care, and design. When mindsets shift, so too can policy.