In a small south suburban school district in Illinois — Dolton School District 148 — a fifth of the students met state reading requirements in 2024. The predominantly Black community has faced economic challenges for years, including property tax hikes. Yet, the former superintendent of their district earned a total compensation of more than $537,000 last year, according to state records.

Kevin Nohelty, who was the district’s superintendent for seven years until his abrupt retirement in August, earned a base salary of $450,000, with an additional $87,000 in retirement benefits and other perks. This made him the highest-paid superintendent in the state in 2024, with a paycheck bigger than the president of the United States and the Illinois governor.

By comparison, former Chicago Public Schools CEO Pedro Martinez earned roughly $356,000 in total compensation in 2024 while overseeing more than 600 schools with 300,000 plus students. That is roughly $180,000 less for overseeing more than 100 times as many kids as Nohelty’s former district.

Given a superintendent’s role in shaping academic outcomes, managing budgets and leading district strategic planning, it is reasonable to expect compensation to be linked to the district’s size, wealth or student performance, experts say.

But the data tells a different story.

A Tribune analysis of 2024 salaries found that at least 18 suburban superintendents in Illinois received higher compensation than Martinez despite overseeing significantly smaller districts. Collectively, these 18 superintendents oversee 117 schools serving 76,000 students — roughly 600 fewer schools and 230,000 fewer students than Martinez.

Experts themselves even find difficulty in contextualizing superintendent salaries and definitively stating which factors weigh the most. However, the main concern for residents such as Toni Cusimano, who lived in the south suburbs for decades, is how these complex compensation systems and financial decisions affect the lives of children and families.

“I think it’s a shame that people make that much money in a community that is so poor,” she said, referring to the Dolton school district. “It’s a shame in general to get paid that much for any school district. … The kids are the ones who lose out.”

Overview of superintendent salaries

Rich Township High School District 227 is another example of the disconnect between school district size, student achievement and executive compensation. In 2024, Johnnie Thomas earned a total compensation of more than $423,000 — the fourth-highest in the state — to oversee a single school with about 2,300 students. Only a tenth of its predominantly Black student population met state reading standards.

By comparison, Adlai E Stevenson High School District 125’s superintendent Eric Twadell earned slightly less — more than $380,000 — while managing a single school nearly twice the size, with over 4,500 students. More than half of Stevenson’s students met the state’s reading requirements in 2024, when the superintendent ranked ninth in total compensation.

Neither Thomas nor Twadell responded to requests for comment.

Despite overseeing vastly different numbers of schools and student outcomes, the top 10 highest-paid superintendents received total compensation topping $4.2 million, with median base salaries of more than $400,000, according to the Tribune analysis. Statewide, the median superintendent salary is $155,000.

Harvard University professor Paul Reville, an expert in the practice of educational policy and administration, said above-market salaries are most often seen in more affluent communities.

“Where I’ve typically seen the kinds of situations you describe — where salaries are way above what the market average — tend to be in wealthy suburban communities where they have more resources at their disposal than other places,” Reville said. “So, they’re willing to bid for high talent that might go elsewhere.”

In Illinois, however, the top 10 highest-paid superintendents in 2024 represented a variety of communities. The list includes wealthy areas such as North Shore School District 112, where Superintendent Michael Lubelfeld ranks as the state’s secpnd highest-paid public school administrator last year with a total compensation around $480,000, and working-class towns such as Chicago Heights District 170, which is overseen by the state’s sixth highest-paid superintendent, Thomas Amadio, who was paid $411,000 in 2024.

Amadio did not respond to a request for comment.

In a statement to the Tribune, Lubelfeld said his compensation reflected the critical and difficult nature of his job.

“My compensation is set by the Board of Education through a multiyear contract that reflects the responsibilities of leading a large and diverse school district,” he wrote. “As I look ahead to retiring in June 2026 after 33 years in public education service, I’m confident the progress we’ve made puts the district and its children in a great, secure place for their future.”

The district’s school board wrote in a statement to the Tribune that they “stand by this decision as essential to retain him through these formative years.”

Several superintendents earned more than Gov. JB Pritzker, who forgoes the salary because of his personal wealth. Beyond the governor, the top five highest-paid superintendent salaries surpass those of other state officials, such as the secretary of state and attorney general.

Education expert Bruce Baker, a professor at the University of Miami, said that school district superintendent salaries take on a new meaning when compared across taxpayer-funded jobs.

“If you try to compare them across other kinds of public sectors and public intersecting sectors and try to do it on the basis of enterprises of similar magnitude, then the public school superintendent’s salary ends up not looking very hot,” Baker said.

Baker suggested that comparing superintendent salaries to private school headmaster salaries could provide more insight into the market value for a top administrator. For example, Francis W. Parker School’s headmaster made nearly $1 million in compensation in fiscal year 2024, nearly $400,000 more than Nohelty, according to tax records.

Beyond total compensation, knowing its share of the total budget can clarify how resources are distributed in a school district. Total operating expenditures include costs associated with daily operations, utilities and maintenance, instructional materials and salaries.

Among the districts with the 20 highest-paid superintendents, Ford Heights School District 169 spent 2% of its total operating expenditures on the superintendent’s salary — the largest share in the group. Martinez and CPS had the smallest share of the group.

Compensation packages for superintendents have long been reliant on performance-based metrics, such as the superintendent’s ability to meet the district’s goals outlined in their contract. These goals can include improving test scores or tackling chronic absenteeism. But education experts argue that these metrics are only partially helpful in determining whether a superintendent has been successful at their job.

“We know that test scores can be really hard to change in that the biggest indicator of performance on a test is often parent wealth or parents’ socioeconomic status,” said Rachel White, founder and lead researcher at The Superintendent Lab.

Several experts also told the Tribune that pay should reflect the magnitude and complexity of the job, which is why many were surprised to see Martinez, the former CPS CEO, ranked so far down the compensation list. In addition to overseeing the state’s largest district, Martinez also had to grapple with crippling debt, contract negotiations with a powerful teachers union and a mayor who wanted to oust him last year.

“Pedro should be 100% on top of the list,” said Mark Friedman, an education consultant and a retired Illinois school superintendent. “Pedro should have gotten half a million dollars to deal with what he had to deal with; That man’s life was miserable his last year.”

A deep dive into Nohelty’s contract

Superintendent salaries have long made headlines in the Chicago area, reflecting a public interest in how local tax dollars — school districts typically get the biggest cut of property tax bills — are spent.

Last month in Elgin, District U-46 Superintendent Suzanne Johnson signed a new five-year contract with a base salary of $300,000 per year, with raises between 3% and 5% annually. The contract states that Johnson, who oversees the state’s second-largest school system after Chicago, will work to improve students’ literacy and math skills, develop a plan to increase attendance to 90% and enhance the district’s culture.

In March, the Oak Park Elementary School District 97 school board voted to give Superintendent Ushma Shah a two-year contract extension that would give her a retroactive 3.4% raise and increase her salary to $238,117.28 as she oversaw a system with 10 schools and 5,600 students. Shah stunned the community in August when she abruptly resigned after alleging the board was about to impose a “punitive action.”

The move left the district scrambling to enact a leadership plan as the new school year began.

No contract, however, has sparked more controversy than Nohelty’s deal.

Nohelty, hired by the Dolton School District 148 in 2018, initially earned a base salary of $285,000. He was set to earn a base salary of $480,000 for the 2025-2026 school year, the outcome of a two-year contract extension approved by the school board in March. He would have earned a $30,000 raise each year as part of his deal — with an estimated total compensation of nearly $600,000 by 2027.

According to his contract, Nohelty was expected to meet three goals related to academic improvement and student performance, such as implementing improved methods to assess and evaluate student performance. Residents such as Kathy Cherry, a retired District 148 teacher and Dolton community member for more than 30 years, said that considering the district’s test scores, neither a contract extension nor a raise should have been considered.

In 2024, only 7% of students in the district met or excelled in math, as well as 17% in science. Statewide, nearly 28% of students were proficient in math and 40% in science in 2024, meaning District 148 is below the state average in reading, math and science.

“As a former teacher, I am pretty disappointed,” Cherry said. “I live in this community, and we hope for the best for our kids.”

Nohelty did not respond to requests for comment.

“His retirement is a blessing for the community,” said Susan Klumpner, executive director of The ACE Project, which worked with the district until last year. “I keep shaking my head about this situation because the people that are hurt the most are the kids within the school district. And if this is a bunch of adult political nonsense, shame on all the adults.”

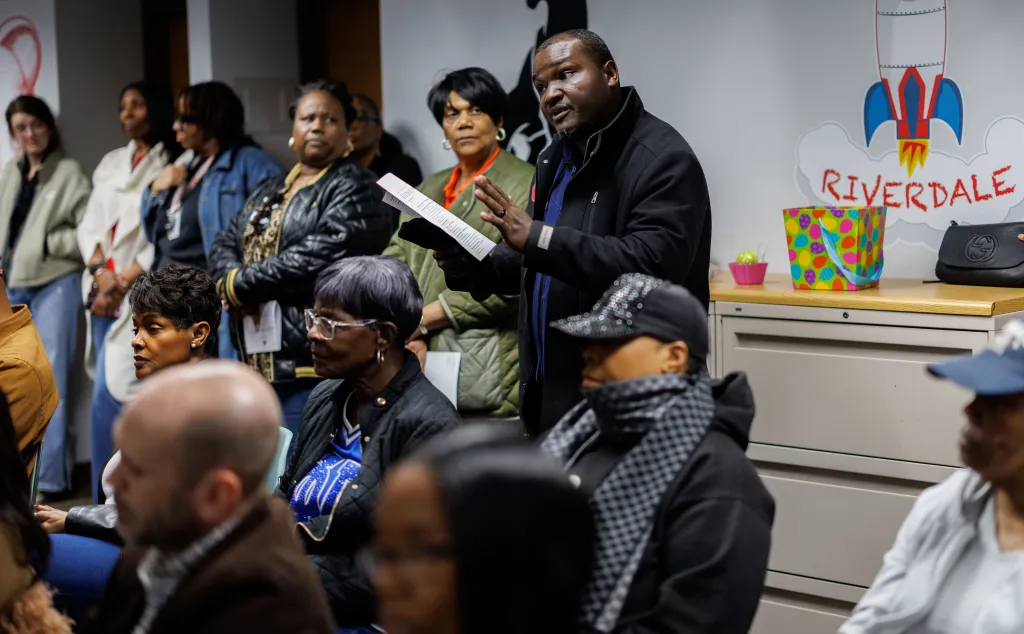

Riverdale resident Michael Smith said he’s frustrated that taxpayers will now be responsible for helping to pay Nohelty’s pension.

“Here we are, paying our taxes, and we’re thinking we are receiving the services that we should and our children should,” Smith said. “And they’re not.”

The school board confirmed that Nohelty will receive retirement benefits starting Oct. 1, although the amount is unknown at this time.

As the district searches for its next leader, the school board has hired Sheila Harrison-Williams, a retired superintendent from Hazel Crest School District 152 1/2, as its interim superintendent.

She is being paid $1,500 per day, according to her contract.