By Nasratullah Taban

Copyright thediplomat

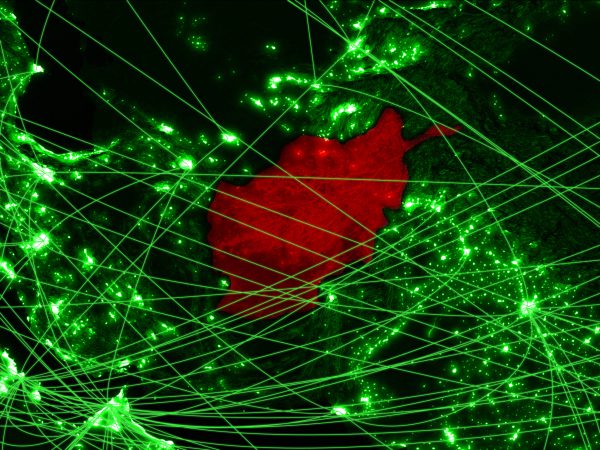

On September 15, 2025, Taliban leader Hibatullah Akhundzada announced the shutdown of fiber-optic internet across Afghanistan. The ban was implemented the next day in northern Afghanistan’s Balkh province. Taliban officials told the media that the order came directly from their leaders and justified the restrictions as means to curb “immorality.” Many Afghans fear this could be the start of permanent internet cuts across the country. Two decades ago, Afghanistan boasted one of the region’s most vibrant media landscapes. In the years after the Taliban’s fall in 2001, more than 600 media outlets operated nationwide, employing both men and women as journalists and media professionals. However, journalists remained targets for the Taliban and other extremist groups; in 2016, a car bomb attack by the Taliban killed seven Tolo TV staff in Kabul. Social media and internet services became popular, reaching around 9.2 million Afghans as of 2022. Despite high costs and slow connections, young people in major cities used the internet to publish articles critical of the government and openly criticize local authorities. Afghanistan’s Constitution protected the freedoms of speech and media. Article 34 stated: “Freedom of expression shall be inviolable. Every Afghan shall have the right to express thoughts through speech, writing, illustrations as well as other means in accordance with provisions of this constitution.” All these gains were dismantled after the Taliban regained power in mid-August 2021. Many media professionals fled, more than 400 media outlets shut down, and women were banned from working, including in media. From day one, the Taliban prohibited women’s faces and voices on television and radio. Media outlets now require approval from Taliban authorities to air any news, reports, articles, or documentaries. The recent internet blockage, starting with the north, adds to previous restrictions, which included blocking TikTok, the video game PUBG, and pornography websites. These measures also extend beyond media and entertainment, targeting women and girls in daily life. Secondary schools and universities have remained closed to female students for four years; women are barred from employment. For a woman, even leaving the house without a male guardian is forbidden. International support has attempted to fill the gap. Many universities and colleges abroad offer online classes for Afghan girls, and members of the Afghan diaspora have launched online platforms to continue education. Recently Indian government announced 1,000 online scholarships for Afghanistan students. Afghan girls now fear that a complete internet shutdown will cut off these essential opportunities. Afghan female journalists and media workers have also been hit hard by the ban. Restricted from travel and work, they rely on the internet for education and income, including selling handmade crafts, clothes, or homemade food online. The internet ban threatens both their livelihoods and their education, undermining a critical avenue for independence and empowerment. Meanwhile, the Taliban continue to arrest social media activists who challenge their ideology. The U.N. has documented 256 instances of arbitrary arrest and detention of journalists and media workers since the Taliban’s return. On one hand, the regime shuts down local media; on the other hand, its officials actively post on platforms like Facebook and X, maintaining verified accounts and a global audience. The Taliban have also invited foreign social media influencers, including YouTubers, to Afghanistan to travel freely and promote a positive narrative abroad. Soldiers have been photographed with female foreign social media influencers and shared these images online, while simultaneously restricting Afghan women’s voices in local media. This raises a crucial question: Why restrict local media while leveraging the same platforms for international propaganda? Experiences from the Taliban’s first regime (1996-2001) show their longstanding hostility toward independent media. Today, they use digital platforms to recruit, spread propaganda, and build legitimacy, amplifying their influence far beyond Afghanistan borders. These tools are used to reinforce the regime and its narratives, while the Taliban in turn restrict the use of the same platforms by Afghan women, blocking their stories from being told.