We gathered in some forgettable parking lot, the six of us, and climbed into Lorenzo’s Ford. That beat-up, forest-green, 1990-something F-150 extended cab with its makeshift door handle — a metal bolt tied to a string. Four of us scrambled into the back, while Lorenzo sat shotgun and Richard drove, eager for a crack at the manual transmission.

I carried an orange-handled fillet knife on my belt, deputized as the only one who really liked fishing to lead us to a good spot. Truth be told, when we set out from Miami headed west on U.S. Highway 41, I didn’t know where we were going. All I knew was that out that way, there was plenty of water and not much supervision, so out that way we went.

We passed the Miccosukee tribal casino, marking the end of municipal sprawl and the beginning of the Florida Everglades, where the salty breeze gives way to the thick, heavy air of the swamp. We passed levies and dams and tourist traps hawking airboat rides. But mostly, we passed little at all — mile after uninterrupted mile of brown sawgrass, peppered by occasional street signs.

Those signs included one, unnoticed at the time, for the “Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport” — a space that would later host the immigration detention facility known to the nation as “Alligator Alcatraz.”

Announced in June 2025 by Florida Attorney General James Uthmeier — and enthusiastically backed by Gov. Ron DeSantis — Alligator Alcatraz became a summer-long political battleground. By fall, its future was uncertain.

A federal judge in Miami ordered it closed by late October for violating environmental laws. The state appealed, with backing from 21 other Republican-led states, to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta, where judges halted the injunction while they mull over the state’s argument. Meanwhile, state officials plan to “ramp up” the operation with the dispute stuck in court.

I of course couldn’t imagine the place we were headed would ever be national news, or a flashpoint in a heated argument over immigration policy. I couldn’t imagine it would ever even have a name. To me, it was just a fishing hole.

Our first spot, which I chose, was a dud. We caught a few small fish, which felt worse than catching nothing, given the day’s expectations. Piling back into Lorenzo’s Ford, we hit the road again and stopped at what looked to us like an abandoned campsite. At the campsite’s center was a rock pit lake — a big hole in the ground with shallow, uniform banks that dropped into a deep, black abyss.

Similar lakes dimple neighborhoods across South Florida because they allow for land development: The earth pulled from the lakes is used to elevate the surrounding swampland and make it habitable. But the left-behind lakes can themselves become ideal habitats, too. This one was full to the brim with dozens of alligators, their telltale eyes and noses jutting from the still water in every direction, and their deep, bellowing clicks echoing every now and then from hideaways seen and unseen. A few paddled along slowly with their mighty tails.

Lorenzo had brought raw chicken breasts to use as fish bait, warm and sticky, but being 18 (or close to it), curiosity nudged us toward a different application. I rummaged through my tacklebox and found the biggest hooks I had — some completely impractical monstrosities designed to catch sharks. I fastened one to the end of a six-inch steel leader, then sliced off a chunk of chicken with my knife.

It was swallowed immediately by a juvenile gator, maybe three feet long. We reeled until our line howled like a fast-closing zipper. The gator fought. It thrashed. And Oscar referenced Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea,” which we’d all read in eighth grade. We needed to respect our catch, Oscar said, just as Santiago, the novella’s protagonist, respected the marlin he’d battled.

Instead, when that gator got too close to shore, we cut the line and ran. I’ve often thought about how, at the bottom of that rock-pit lake, a young gator’s skeleton probably rests with that big hook still lodged in the bones of its throat.

A part of me doesn’t really want to stare down the contrast between this vision I built — this monument to an idealized future full of thrills and potential — and what’s really lurking out there.

We decided to go home, but we made one last stop at an isolated convenience store on the way. It stood beside a dusty ramp into a canal, and we could see fish in the amber-tinted water, so we decided to give this fishing thing one more try. What followed was the best fishing day of our lives.

We caught everything. Two, three at a time. Largemouth and peacock bass. Giant bowfin. Even a chain pickerel. That spot, starting right then, became my go-to honey hole. I went back again and again. I brought friends old and new. My uncle. My dad. Even my wife.

That day in 2014 also marked, for me, a taste of what felt like true freedom. We were just kids in a beat-up Ford with busted handles, chasing fish we barely knew how to catch, and gators too. We agonized over our future constantly, every one of us. We all wanted to be successful, whatever that might mean. We all worried about getting there. But for a few hours, it didn’t matter where we’d end up.

Eventually we headed home, once more traversing sun-bleached U.S. 41, where we’d passed that sign for the Dade-Collier Training and Transition Airport that, 12 years later, would be replaced by a new, more menacing one.

What once is lost

The first group of detained migrants arrived at what used to be an abandoned airstrip on July 3, 2025. The facility, nicknamed “Alligator Alcatraz” by Florida’s branding-forward attorney general, boasted an initial capacity of 3,000 with room to expand.

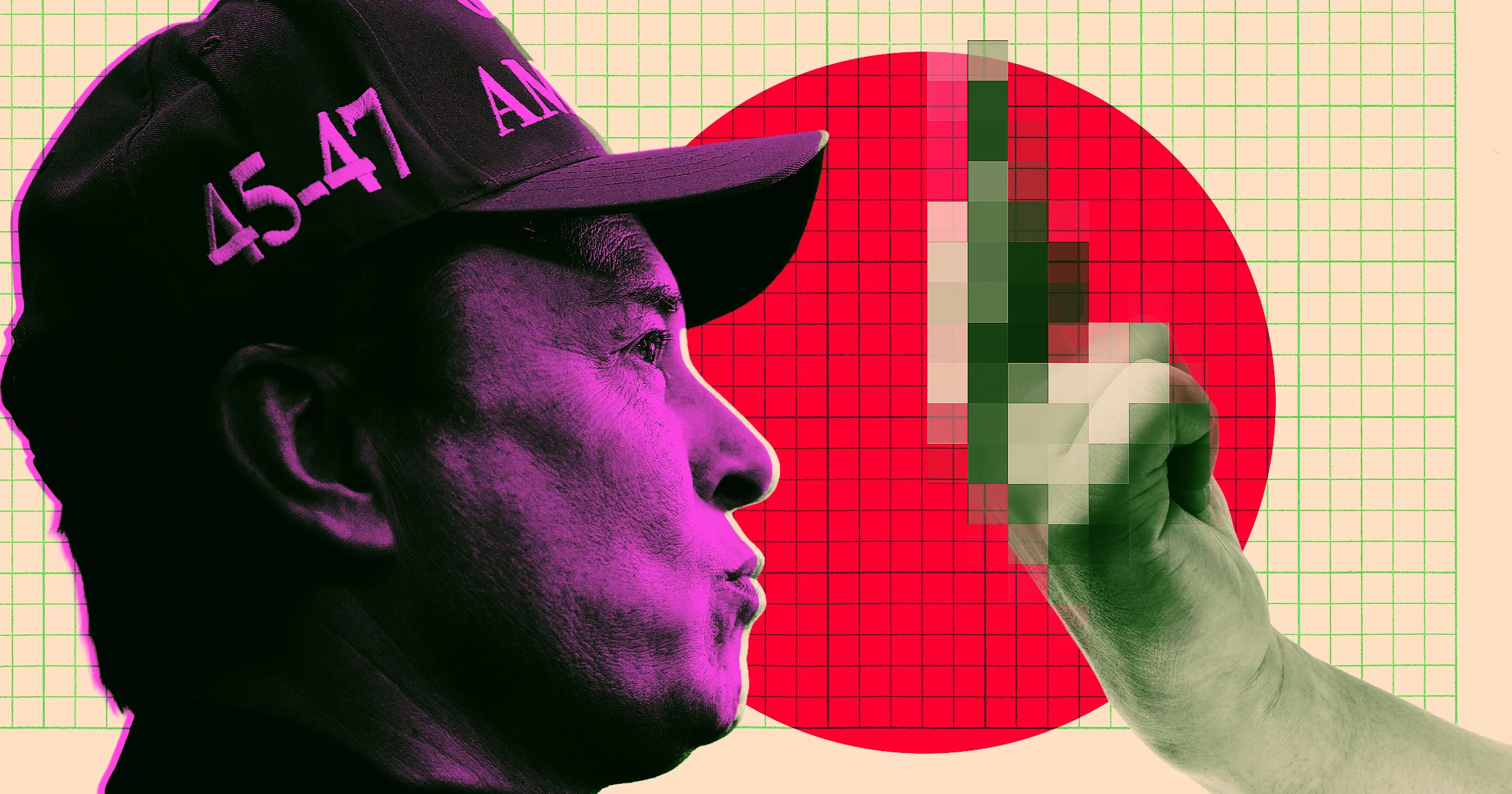

Its construction was spearheaded by DeSantis, who sees it as a crucial step in helping implement the mass deportations favored by President Donald Trump and Republican leaders. Trump himself toured the facility on July 1, saying “it might be as good as the real Alcatraz.” And Florida’s attorney general has touted the detention center’s natural perimeter — a landscape stalked by sharp-toothed, muscular beasts.

The alligators, snakes and isolation make escape unthinkable — not to mention terrifying, which is the point. He and fellow Republicans have used that fact to market Alligator Alcatraz merchandise online, including hats, T-shirts, bumper stickers, buttons and more. According to one official, it’s “selling like hotcakes.”

A few more miles down U.S. 41 is a roadside stop called the Big Cypress Gallery. Founded by fine art photographer Clyde Butcher, the compound, built right into a dense cypress stand, hosts art exhibits, vacation rentals and “swamp walks.” Back in December 2023, the latter brought me to the gallery, and to Scott Randolph.

He lives nearby and leads paying visitors like me on wet, waist-deep slogs through the slow-moving murk. Out there, in the deep middle of the Big Cypress National Preserve and the larger Everglades ecosystem, the sloshing of our pants through the still water was by far the loudest noise within earshot. Every bird could be heard. I wondered whether any of that had changed since Alligator Alcatraz opened, so I reached out to Scott. “The impacts here,” he wrote via email, “are impossible to ignore.”

As Everglades conservationists know all too well, once something is lost, it can be nearly impossible to restore what was.

On July 13, he participated in a protest at the gallery, along with hundreds of others. The protesters focused almost entirely on the facility’s environmental impact. “This ecosystem has already been crippled by human interference, reduced to less than half of its original size,” Scott wrote. “To now propose cramming 3,000 to 5,000 people into its fragile core is not only reckless — it is an outright assault on one of the world’s most vital and vanishing landscapes.” His thinking reflects a decades-long tension, brought explosively back into the spotlight.

What is now Alligator Alcatraz was built atop an airstrip first constructed in 1968, intended as the beginning of a new jetport. But by the mid-1970s, the project had been abandoned. “It was established in 1975 that you can’t have anything like that,” Butcher told me recently. “There were all these environmental studies back in the ’60s and ’70s that said this was not acceptable.”

Advocates have since convinced the state to earmark billions toward Everglades restoration projects. But Alligator Alcatraz is a major setback. “The first thing that really got me mad was they said this is a disgusting, horrible place with alligators and snakes. That it’s no good for anything,” Butcher said. “I’ve spent 40 years trying to convince everybody it’s a beautiful place. It’s probably the most beautiful place in the United States.”

It’s striking indeed to contrast Butcher’s work, defined by arresting black-and-white landscapes of the Everglades that invite viewers into the distinctive space, against Alligator Alcatraz merch that uses bold lettering and glowing red eyes to convey fear and brand the Everglades as a space of inescapable suffering. Butcher’s portraits decorated the walls of my childhood home, and still hang in my parents’ hallway. Yet I haven’t really noticed them in a long time.

What I do see driving around Florida are Alligator Alcatraz bumper stickers, embodying the aggressive, cartoonish encouragement from state leaders to “keep Florida tough on crime and tougher on borders,” per a fundraising email from the Republican Party of Florida; to paint the Everglades as “gator guarded” and “python-patrolled.”

Republicans argue that failed Biden-era immigration policies need to be corrected quickly, hence the need for a place like Alligator Alcatraz; that it’s a moral duty to facilitate the will of voters, and deport immigrants in the country illegally as quickly as possible. Opponents, meanwhile, largely view this approach as undignified and inhumane.

“The cruelty is the point,” said Democratic Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz during a July press conference. “This is a stunt. I mean, dropping flimsy infrastructure in the middle of the Everglades, in a swamp where they bragged about it being surrounded by alligators and pythons, I mean, the whole point is to look tough.”

And to many, it does. To many, this is what immigration enforcement, and the country more broadly, should look like. But not to Scott Randolph. “When we strip others of that dignity, we strip it from ourselves,” he told me. “The decision to place this facility in the heart of the Everglades only compounds the injustice.”

As Trump’s cultural revolution continues, big change is undeniably here. But however you feel about the changes, it’s also worth remembering — as Everglades conservationists know all too well — that once something is lost, it can be nearly impossible to restore what was.

A paradise all its own

Within view of the entrance to Alligator Alcatraz, U.S. 41 curves at a diagonal angle. It continues at that angle for about 10 miles before curving back toward its original, straight-across-the-state trajectory. There, at that second curve, lies the convenience store that offered refuge to my young self all those years ago and in all the years since.

Named Tippy’s Outpost after a Miccosukee alligator wrestler, it serves hot food, including fried gator nuggets, alongside baked goods, cold drinks, air fresheners, potato chips and a modest stock of fishing hooks, bobbers and monofilament. I’ve rarely been inside. Over the years, Tippy’s became, for me, more a point of orientation than a place to shop. A dot on the map that told me I had arrived where I needed to be. Unlike back in high school, once I found Tippy’s, I always knew where I was going when I set off down U.S. 41.

Tippy’s itself is modest: One small room, with some outdoor seating running parallel to a canal out back that meets a boat ramp and, past some colossal cell towers rusting in the sun, opens up into a much larger body of water that brushes up against a human-made levy. The boat ramp and levy alike attract fish, giving Tippy’s an angling turbocharge.

In South Florida, freshwater fishing is already paradise. From native largemouth to Amazon-imported peacock bass, the climate breeds abundance. So much so that people release their overgrown pets, leading to certain aquarium fish thriving across the Everglades. But there are also less common catches — red-bellied pacu, tiger shovelnose catfish or, God help you, Burmese python, which I’ve seen dead on the road not far from Tippy’s. With vultures perched on the rusted cell towers, insects rattling away in the sawgrass, and the slimy stink of fish assaulting both nostrils and hands, Tippy’s is a subset of paradise all its own.

It’s where I brought my dad and uncle for days spent together, just the three of us. Where I came alone during winter break in grad school, desperate to reconnect with the landscape I loved. And it’s where I’ve encountered the Everglades’ apex predator countless times — alligators that have chased me, attracted by the slapping sound of my catches breaking the water’s surface.

I’ve watched them slither across the glassy canal, then rise up on their awkward wiener dog legs to growl and attempt thievery. Once, when I tried to retreat, my line snapped. My catch splatted onto the ground, and a hungry gator lumbered over, snatching it in toothy jaws.

The poor fish could only release the involuntary, desperate sound of a deflating tire as the gator punctured its swim bladder before slurping it down whole. That sound — the sound of death — echoes still in my memory. In the Everglades, the strong chase the easiest prey, and the prey disappears with a whimper.

We didn’t know about such dangers during that first trip. When someone’s fishing line snagged on a rock, Lorenzo was willing — hesitantly — to dive into the murk and free it. He shed his sleeveless shirt and the thick, black eyeglasses he’d worn as long as I’d known him and walked his short, lean frame into the muddy trench, kicking up a trail of fine sediment. For just a second, he disappeared beneath the haze, then emerged, hook in hand — and without any bite marks.

I returned throughout young adulthood because the canal behind Tippy’s gave shape to the life I wanted. Here, I felt most American, and most human — most grateful to be alive. Here was a refuge where I could escape hardship and complexity, either alone or with friends brave enough to swim with alligators.

While the Tippy’s of my memory still exists out there in the Everglades, so does this new, competing vision of what the Everglades could become.

Now a part of me dreads heading out that way again. A part of me doesn’t really want to stare down the contrast between this vision I built — this monument to an idealized future full of thrills and potential — and what’s really lurking out there.

Long shadows

Was I always just happy to ignore difficult things? As a teenager and beyond, were my visits to Tippy’s just a way to tune out the less approachable, more uncomfortable parts of the world? That very day we first drove out there, after all, we passed something else unknown to us at the time: Krome Detention Center, a facility that’s likewise located right off U.S. 41, directly across from the Miccosukee casino — and has existed since the Cuban Missile Crisis.

I put this question recently to Domingo, one friend among the six who were there that day. “You know,” he told me, “it’s funny you mention that.” His memory of the Everglades, it turned out, was colored less by that day, and more by snapshots of correctional facility vehicles he’d sometimes see in the area. “I mean, obviously, I thought it was kind of a gimmick when I first heard about ‘Alligator Alcatraz,’ he adds, “but it was interesting because I always kind of associated (that area) with a prison.”

Nowadays, Domingo’s an EMT. Richard, so eager to drive Lorenzo’s stick shift back then, is a lawyer who drives a Corvette — with, he adds proudly, a manual transmission. Lorenzo himself has a doctorate in materials science engineering. Our sixth friend, John, is about to become a doctor. Oscar leads a tech startup. We’ve all grown into those futures that seemed limitless when we romped up and down U.S. 41.

In a different part of “The Old Man and the Sea,” Hemingway writes that “a man can be destroyed but not defeated.” Oscar didn’t quote that passage back then, but it applies to the area’s transformation. That day in 2014, we surrendered when that hooked gator got too close. Yet that day also told its own story of resilience. Of learning from mistakes. Of determination — to find fish later on, and to never purposely hook a gator again.

Just as that water surrounding Tippy’s revealed its treasures — the bass, the bowfin, the pickerel — it now reveals something else: that places, and people, can harbor conflicting visions at once. Paradise and prison can coexist in disturbing proximity. And while the Tippy’s of my memory still exists out there in the Everglades, so does this new, competing vision of what the Everglades could become.