When Nathaniel Schumann entered the clinical trial for children with autism, he was 8 years old and considered nonverbal. He communicated through gestures and sounds, which his parents were skilled at interpreting. But two weeks after receiving his first dose of the study pill, Nathaniel began to speak – not just words, but full sentences.

“The first thing we noticed is kind of funny: He had a laundry list of things that bothered him,” his mother, Kathleen Schnier, said.

Anecdotes such as Nathaniel’s have begun to circulate with increasing urgency through online parenting forums and autism support networks. At the center of these accounts is a decades-old drug, leucovorin, a form of vitamin B9, which is also known as folate. It has been traditionally used as an antidote to toxic effects of a certain cancer drug.

New clinical trials – small and carefully controlled – hint at something bigger: For a select group of autistic individuals, leucovorin may boost communication and cognition in ways once thought impossible. Researchers have found that some individuals with autism have difficulty transporting folate – a nutrient essential for neurodevelopment – to the brain and think the medication may help deliver it more effectively. Trump officials are expected to tout its potential Monday at an event about autism, and physicians involved in discussions with the administration say Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. may fast-track approving it for treatment.

Researchers say the hope is real – but fragile.

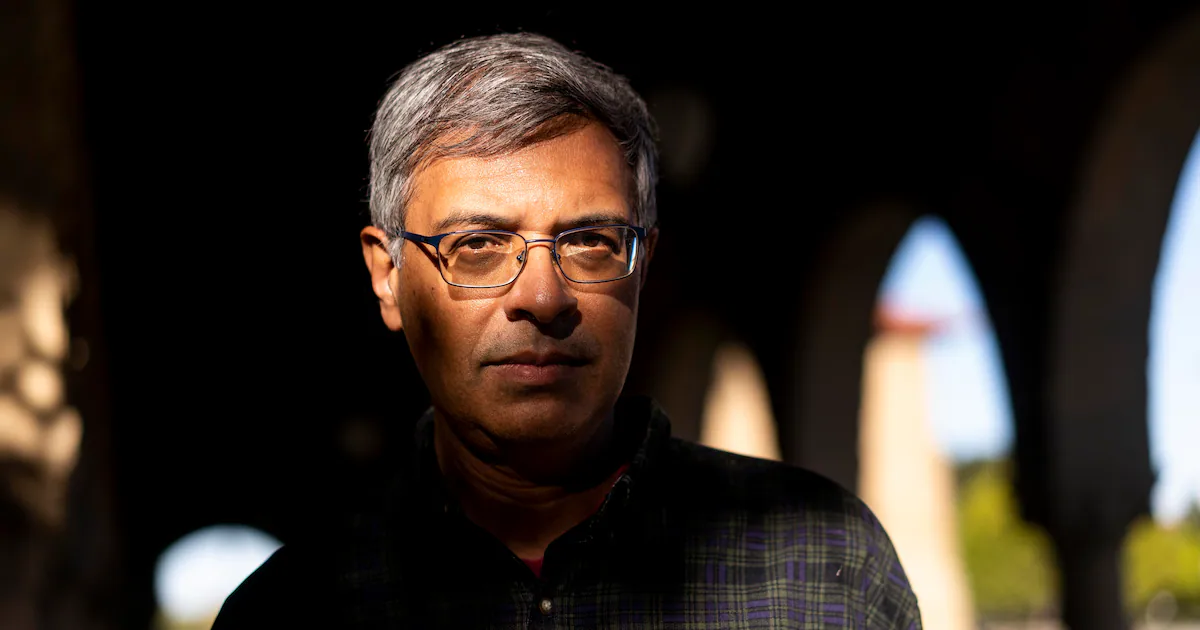

“We’re still on the 10-yard line,” said Richard Frye, a pediatric neurologist who is studying leucovorin, suggesting the research is still near the beginning of the process. “But it’s something that we think might be able to help a lot of children.”

Now, the debate is moving from laboratories to the national stage.

Kennedy’s involvement in setting autism policy has ignited significant controversy within the scientific community since he took office, in part because he has promoted discredited claims linking vaccines to autism – an assertion that has been debunked by decades of scientific research.

Kennedy’s office also has been looking into a possible connection between autism and acetaminophen – Tylenol’s active ingredient – after an Aug. 14 analysis presented compelling evidence linking prenatal use to an increased autism risk in children. While the study was well-received, the online response spun out of control, with some hailing it as definitive proof of autism’s cause and others dismissing it as outright misinformation. Researchers studying leucovorin are hoping to avoid a similar backlash.

The Autism Science Foundation said in a statement that “more studies are necessary before a conclusion can be reached” and that it does not recommend leucovorin as a treatment for autism. Most of the leucovorin studies involved only a few dozen participants each, and numerous compounds appear promising early on but fail when subjected to large-scale trials.

“I don’t think you should go out and use it right now based on the body of evidence that exists, but it’s certainly worthy of further exploration,” Scott Gottlieb, a former FDA commissioner, said in an interview on CNBC’s “Squawk Box” on Monday.

One in 31 8-year-olds had autism in U.S. communities examined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, yet despite decades of research, no approved treatments exist to address its underlying causes.

The idea of using leucovorin as a treatment is challenging the long-standing belief that autism is solely a fixed neurological difference. It touches a nerve in the politics of neurodiversity, where efforts to treat core symptoms are sometimes seen as attempts to “fix” what many consider a natural and valuable variation of the human mind.

The role of folate in supporting brain development is well established, and deficiencies have long been linked to birth defects. A growing number of doctors are starting to prescribe leucovorin – a special type of folate found in green leaves that can enter healthy cells – off label, but scientists urge caution. They say the treatment is still experimental, it appears effective only for individuals with a specific genetic or metabolic profile, and its long-term impacts are unknown.

The concern among researchers is not simply about the drug itself, but also about the perceptions and messaging taking shape around it. Irva Hertz-Picciotto, an epidemiologist at the University of California at Davis who specializes in autism, said scientific progress depends not just on discovery, she said, but on trust. And trust, once lost, is difficult to restore.

“I worry,” she said, “that it feels like everything is now tainted that comes out of the current administration.”

While the research on folate is early and evolving, it’s not fringe science, she added, urging the public to keep an open mind and noting that many significant scientific breakthroughs began with questions that initially challenged conventional thinking.

‘A win’

Research into folate’s role in autism goes back to the early 2000s, when scientists started exploring whether folic acid supplements taken during pregnancy – recommended since 1992 – could affect a child’s brain development.

A key breakthrough in 2004 was the discovery that some children with autism-like symptoms had a condition that blocks folate transport into the brain – even if their blood folate levels are normal. Frye estimates that up to 70 percent of those with autism may have a gene variation that would make them susceptible to this problem.

Frye, director of research at the Rossignol Medical Center in Phoenix, hypothesized that leucovorin might be able to help, and he and his colleagues launched double-blind placebo-controlled trials that were funded in part by the National Institutes of Health and Defense Department. They involved children who took a twice-daily pill version of leucovorin.

The extent of the effects surprised even Frye. In his first study of 44 children with 12 weeks of treatment, 67 percent of those who took the drug saw improvements in receptive and expressive language. Similar successes have been replicated in recent months by researchers from at least four different countries – France, China, India and Iran.

None reported serious adverse events, and side effects such as irritability typically resolved quickly, Frye said.

In late August, Frye and several other scientists met with NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya to talk about autism interventions that they felt were not getting the attention they deserved. Attendees said Bhattacharya zeroed in on leucovorin, and within two weeks his staff put the group in touch with officials from the Food and Drug Administration to discuss how to speed up its approval.

Larger trials of the drug have been slow to launch because of funding challenges, Frye said, as its original patents-dating back to its 1952 approval-have expired, leaving pharmaceutical companies with little financial incentive to support further research.

“There are many people who think autism is not treatable,” Frye said. “It’s a ‘win’ to show that’s not the case.”

Not a magic pill

Although the science is still in its early stages, leucovorin has taken on an almost mythical status among some parents of children with autism, who frequently exchange stories and advice about which providers will prescribe it, optimal dosages and helpful tips. Around $100 per month without insurance – and as little as $10 with coverage – leucovorin is seen as a relatively affordable option compared with the high cost and time commitment of speech, behavioral and other therapies.

The initial step to obtain the pills typically requires a blood test that detects autoantibodies – proteins created by the immune system that attack healthy tissue – blocking a receptor essential for transporting folate into the brain. Those who test positive are significantly more likely to respond to treatment, and those who have positive outcomes tend to follow similar patterns.

Kimberly Baldridge’s son, Ryan Jr., was 6 when he began the medication after several other unsuccessful efforts. At the time, his only form of communication was echolalia – repeating what others said. “They’d say ‘hi buddy,’ and he’d repeat ‘hi buddy,’” said Baldridge, who is from St. Louis. But after starting the drug, “he was pinpointing a conversation back and forth.”

“It seemed like before he was lost in outer space, and this medication I feel like brought him into fully being present,” she recalled.

Now 8, Ryan has started second grade in a mainstream school. His parents say he still has autism – he can become dysregulated, struggles with eye contact at times and remains fixated on airplanes – but they are confident in his future.

Nathaniel is now 12. He is on a swim team, plays trumpet, sings in a children’s chorus and is preparing to get certified in scuba diving – all things his parents never thought possible given his early lack of speech.

“I don’t think it’s a magic pill,” his mother said. “I don’t think a child who couldn’t talk is suddenly going to recite Shakespeare and talk politics, but what we’ve seen is a more gradual change, and for our son, that change has changed his whole life.”

– – –