In 2015, Clyfford Still Museum curator of collections Bailey Placzek was cataloging portraits the artist made of Colville Tribal members during the 1930s when a suggestion from Tribal artist and professor Michael Holloman caught her off guard. Holloman was in Denver to collaborate on Clyfford Still: The Colville Reservation and Beyond, 1934-1939, the museum’s first focused look at Still’s work from his summers in Washington.

“He planted the seed back in 2015 for us,” Placzek recalls. “He said, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if the museum could reach out to the community and get to know some of the ancestors of these people who Still met and drew nearly a century ago?’ It was like, ‘Oh my God, that would be incredible,’ and that idea stayed with me.”

Roughly a decade later, that idea has become reality. On September 19, the Clyfford Still Museum opened “Tell Clyfford I Said ‘Hi’”: An Exhibition Curated by Children of the Colville Confederated Tribes. The project brings together Still’s depictions of Colville ancestors and landscapes with the interpretations of young people who live on the same reservation today. Installed across all nine galleries, the exhibition places children ages three to fourteen and Colville teachers in the role of curators, shaping the selection, arrangement, gallery text and interpretation of more than 80 works.

“It’s really powerful that the children we’re working with for this exhibition have a connection to these artworks,” says director of learning and engagement Nicole Cromartie. “All children connect to artworks intuitively, but some of our co-curators were saying, ‘Oh my gosh, that’s my great-great-grandmother.’ They have an actual ancestral connection to some of the portraits, which was a really incredible way to learn more about our collection.”

The museum’s path toward this collaboration was shaped by an earlier experiment. In 2019, Placzek and Cromartie started working with local schoolchildren on a project called Clyfford Still, Art, and the Young Mind. In the show that debuted in 2022, local children from infancy to elementary school age in seven different partner schools across the Front Range helped select and interpret works.

“The youngest members of our community are often not considered important cultural participants, and surely not collaborators in museum practice,” Cromartie says. “But that was something that we were really interested in changing.”

While Young Mind was in development, Placzek also began deepening ties with Colville scholars. In 2021, she made her first visit to the reservation, sharing resources and beginning conversations about what a partnership with the museum could look like. A year later, the museum put on a big program about the visit with Holloman and John Sirois, traditional territories advisor for the Colville Confederated Tribes.

“That’s when we asked, what’s next?” Placzek explains. “Young Mind had just closed, so it was fresh in their mind, and John [Sirois] and Michael [Holloman] were like, ‘We want to do that in Colville. We want you to make an exhibition with the Colville youth.’ Nicole and I were sitting next to each other at dinner, and we were so excited to just do it all over again. We were like, ‘Let’s do it; that’s perfect.’”

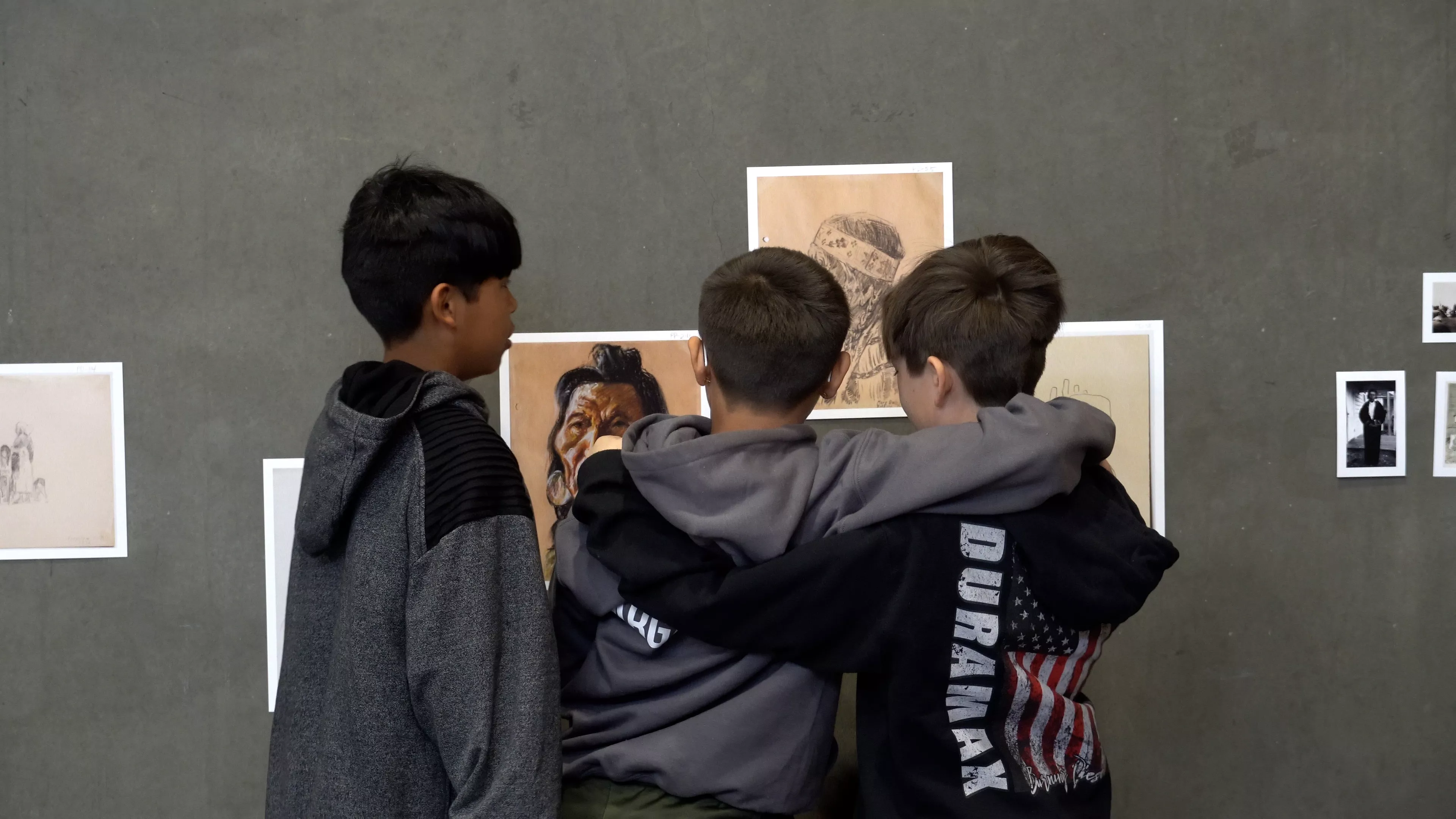

The process took place over the last three years during visits to the reservation, where museum staff brought reproductions of Still’s work for the children to explore. The young curators came from classrooms at Nespelem School, Colville Head Start and Gathered Hearts Montessori. Some recognized their ancestors in portraits, while others responded to his bold abstractions.

“The kids jumped right into it,” Cromartie says. “They were so confident and ready to share their perspectives about works from the 1930s on the reservation, also still really abstract works that intimidate a lot of adults.”

As the conversations unfolded, the children began identifying the themes that would anchor the show – Family & Culture, Connection, Imagination, the Outside, Love and Paint & Color. They also made it clear they wanted to create art themselves, not just talk about Still’s.

“Across all ages, they wanted to make art, so we did that,” Cromartie recalls. “We created a full art day where local Tribal artists engaged with the students in different forms of art making. It was just the most joyful, beautiful experience, and it convinced us that the exhibition needed to honor that impulse with something hands-on.”

That instinct echoed what Placzek and Cromartie had learned from Young Mind, where an interactive component had been one of the most popular aspects. For “Tell Clyfford,” they worked with artist Carly Feddersen to develop a Weaving Wall inspired by Still’s painting PH-796, which one student compared to a blanket. Visitors will be able to contribute to the wall themselves, extending the spirit of creation that guided the young curators.

By the end of the process, the children had chosen dozens of works for the final exhibition, including several pieces that had never before been on view. Placzek said watching the choices unfold shifted her own relationship with Still’s art.

“It made the works come alive in a completely different way,” she says. “When you come to a museum, you’re used to seeing work that feels removed from your present. But when you’re up there and you’re seeing the hills that are in the works, you feel like this could have been done yesterday. When you’re talking with people, it’s like, ‘Oh, that’s my great aunt,’ or ‘That’s my grandpa; I remember watching Superman with him.’ Looking at these artworks evoked memories for co-curators, which brought the work to life in ways I hadn’t considered before.”

At the same time, Placzek acknowledged the fraught history behind Still’s time on the reservation. As a young professor, he painted Colville community members for small sums before leaving, and the works eventually entered the museum’s collection without input from their descendants.

“There’s so much problematic history, obviously, with Still’s own experiences there, and going and painting these people for nominal sums, and then leaving,” Placzek says. “His daughter talks all about how excited she was for us to work on this show, because she remembers him talking about how impressed he was by the people, and how it did have a profound impact on him. So I think that our ability to carry on or reactivate that legacy has been really exciting.”

For Cromartie, the significance lies in what this shift represents for both museums and the communities they serve.

“It’s such an incredible honor to be able to play a role in realizing children’s rights to culture, to true participation in culture, not just being present or allowed into a space, but to really be able to make decisions and share their perspectives,” she says. “We’re also thinking about Indigenous people’s right to control their own narrative, which museums have historically struggled with. I mean, both of these things, so I believe the fact that we can play a small role in recognizing the rights of these Native children is extremely powerful.”