Some years ago, I was interviewing a Columbia neurologist for a potential article on imaging. After a tour of her laboratory and MRI scanner, dialogue about the frontal cortex and the mysteries of synapses, she offered a simple declarative sentence: “We are our brains.” I recalled her pithy comment throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, as clinical evidence emerged that the virus had targeted our brains, among other organs, leaving a biological marker on many (most?) of those infected by SARS-CoV-2 (the official name for the virus, distinguishing it from the disease). The evidence includes heightened risk for stroke, breaching of the blood-brain barrier and “brain fog,” which can linger for months.

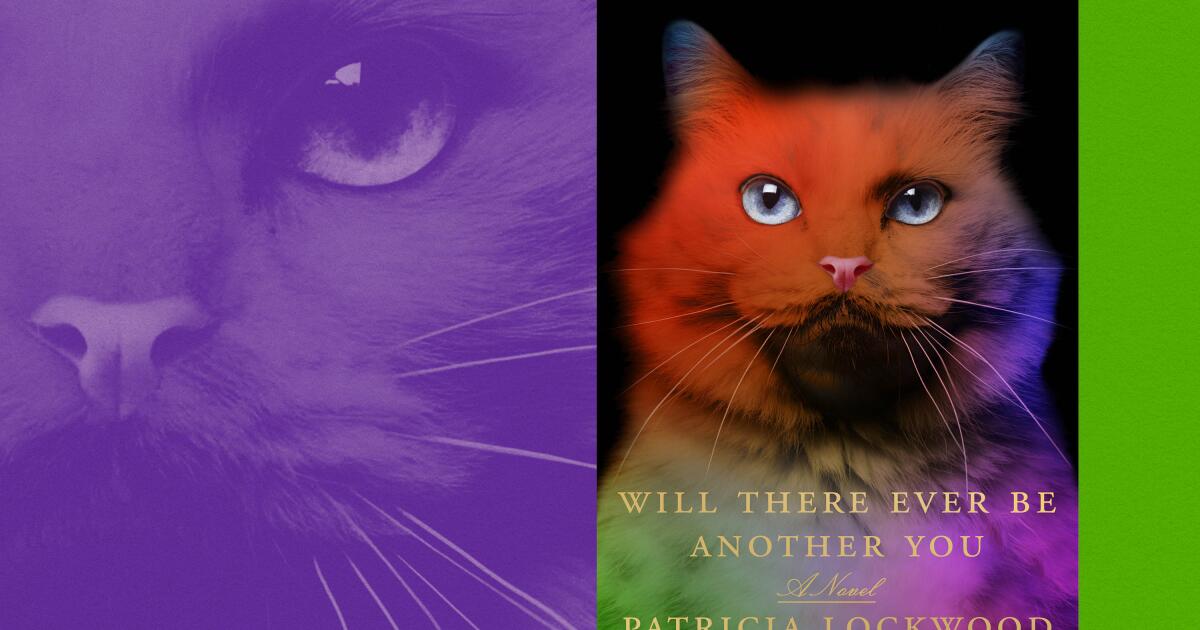

Patricia Lockwood, poet and author of the prizewinning memoir “Priestdaddy,” evokes the pandemic’s long tail in her expressionistic autofiction, “Will There Ever Be Another You,” recounting mind-altering effects on her protagonist, “Patricia,” as she and her husband quarantine in Savannah, Ga., during the initial 2020 outbreak and subsequent surges. A writer, Patricia published a confessional work about her family that she is adapting into a screenplay; as her extended illness kicks in, she finds it difficult to craft anything of merit. She writes snatches of description and dialogue in her journal, but when she reads them later, her words jumble like hieroglyphs. She’s distracted by intrusive thoughts, sentence fragments, out-of-the-blue hallucinations, even her own fraught relationships, placing the blame on SARS-CoV-2: “It has come all this way, she thought, cradling the thing in her chest; has passed through the hands of invention or chance, white lab coats, wet markets, the gates of the zoo … to land in her squarely, like love!” Like Sylvia Plath in her superb poem, “Fever 103,” Patricia struggles with fluctuating temperatures and a sluggishness she connects to her art: “In a story, fever was something that moved you along, sped up time, or made it different, parted the curtain for some ray of revelation — perhaps that’s why the world had decided to have one, so it could have a dream in which all the people were there.”

“Will There Ever Be Another You” drapes a veil over a throughline — occasionally it seems Lockwood has trashed the concept of narrative arc in a fit of pique, as she leaps from setting to setting (Scotland, Cincinnati, coastal Georgia), with uneven results. The action is blurred, her characters faceless as mannequins. Patricia’s husband intervenes valiantly to help her, lending color and wit to her predicament, but we suspect he can’t save her. There are fixed points, though: hospitals, religious anguish, scenes with her quirky family, a fierce desire to reclaim her writing life. They add up to an erasure of self, its meaning elusive: “This was a cardinal sin; you could not become interested in the illness. You could not lavish on it the love and solicitation you had previously lavished on the self, even though it was the thing the self was replaced by.”

From chapter to chapter, Lockwood deploys an associative strategy: anecdotes, memories and social commentary string together, rich and kinetic if confusing. Patricia is both invested in and disengaged from her own mental health and her husband’s medical challenges. Motifs of motherhood shift in and out of view; are the tragedies actual or fever-fantasy? Some jokes hit their marks; others fall flat. Lockwood piles on literary and popular culture references. William Carlos Williams, “Anna Karenina,” Katherine Anne Porter, “Mrs. Doubtfire,” “Cats,” Foghorn Leghorn: all get shoutouts here, a collective distress call that fails to move us. Patricia also bogs down in the details of translating her earlier book into a Hollywood screenplay, with Kurt Russell keen on the part of her father. Americans: We worship celebrity.

“Will There Ever Be Another You” is a portrait of one woman’s crisis, not unlike Plath’s “The Bell Jar,” but without her clarity and acerbic confidence. Lockwood depicts the trajectory of illness through the kind of surrealism that sparked Plath’s “Ariel”; so much depends on how well you absorb the loony-tune Lockwood croons. Patricia enrolls in a welding class as therapy, prompting a bit of internal monologue: “I melted. I could put a spleen back in a human body. Little bodies, drops of overflow. Something began to spin, the sun was coming out. Creatures and plants were raised upon the earth.” A reader’s patience may wear thin. And yet there are moments of startling beauty, such as Patricia’s observation during lockdown, when the natural world took back its turf from us: “We are the plague, people had said at the beginning, rejoicing over pictures of empty streets, of fish and animals shyly returning to natural habitats — and the further she was removed from the world, the more that she felt it was true, that Nature was healing.”

Experimental authors continue to push beyond the boundaries of American realism — Ed Park, Jane Alison and Mark Z. Danielewski come to mind — and at her best Lockwood plays with harmony and dissonance in unexpected, exhilarating ways. She illuminates long COVID, which has rattled the lives of so many. Her meditations on family and loss resonate. But it’s tough to shake the impression that the book’s grand quest, Patricia’s attempt to rescue a self, is self-indulgent and repetitious, spiraling to earth as it tries to soar. “Will There Ever Be Another You” is a mixed bag; readers must sift through “clods” of ornate prose to pluck nuggets of gold.