America, circa now. Things, most of which have been weird for a while, are getting distinctly weirder. The President of the United States is busy redecorating the White House and bent on buying Greenland. A new wonder drug is making people skinny. Domestic affairs are increasingly controlled by an upstart political entity whose official status is murky but whose powers are all but limitless: DOGE, or the Department of Government Efficiency, which was started by a multibillionaire with a sideline in unusual forms of transportation—rocket ships, Cybertrucks, Hyperloops—and named for an internet meme featuring the Comic Sans typeface and a Shiba Inu. Tens of millions of people, followers of a mysterious figure known only by the letter “Q,” believe that many of the nation’s leaders are involved in a global child-sex-trafficking ring that will one day be crushed in an all-encompassing, all-cleansing event called The Event.

Talking dogs, strange vehicles, conspiracy theories, stupid acronyms: life imitates cult fiction, apparently, and somewhere along the line our reality started to resemble, with uncanny specificity, the collected works of Thomas Pynchon. This is not a welcome development, as even his greatest fans would affirm. For sixty-two years—beginning in 1963, with the publication of “V.,” and picking up momentum ten years later, with “Gravity’s Rainbow”—the author has been offering up worlds that seem much like our own except weirder and more lawless, with respect to both criminal activity and physics. The ambient atmosphere in Pynchon’s fiction is one of secrecy and bamboozlement, the purported stakes are generally sky-high but silly, like an armed game of Go Fish, and the possibility of violence on an epic scale is often rocketing, sometimes in the Wernher von Braun sense, directly toward you. Opinions vary on the merits and pleasures of these books, but no one, it seems safe to say, has ever yearned to live in the worlds they depict.

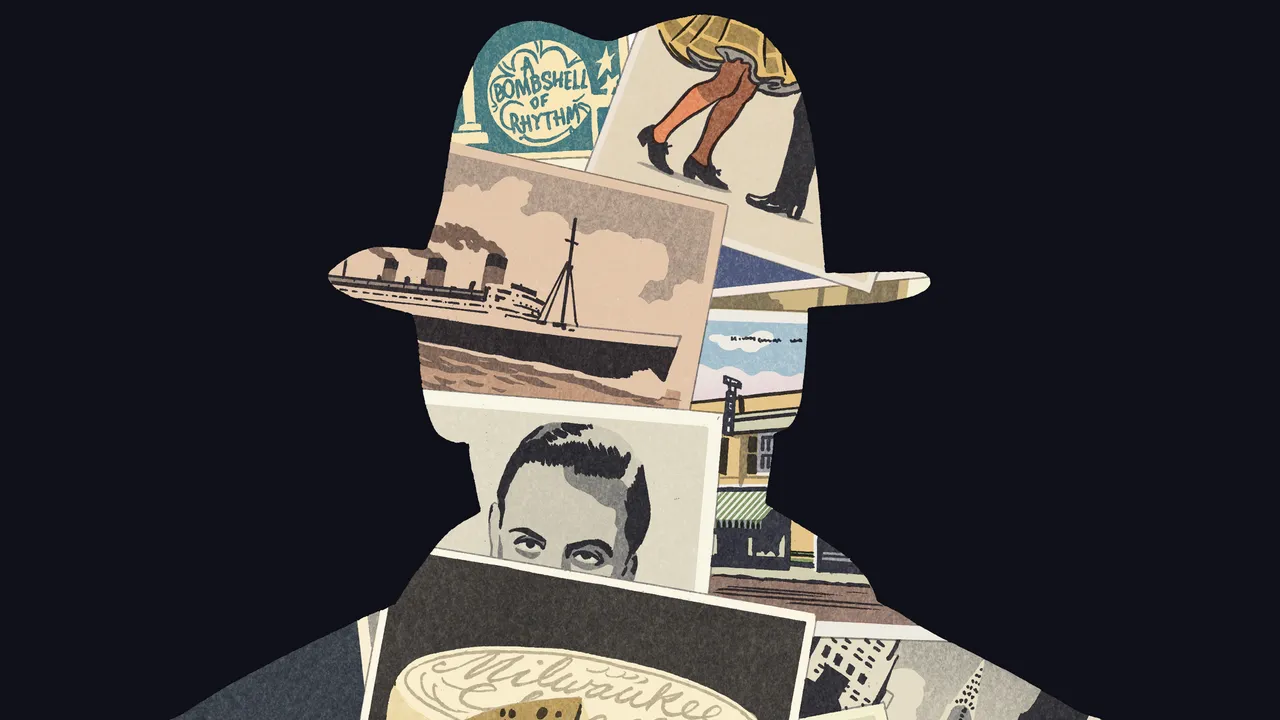

Yet here we are—and here comes “Shadow Ticket” (Penguin Press), the first new work by Pynchon in a dozen years. Although the author is eighty-eight years old, his intellect, at least on the evidence of this book, remains undiminished, which is to say, it is still panoptic, exciting, abstruse, distractible, and, for good or ill, unrestrained. But, if his powers are not dulled, neither are they pointed; even if you squint, it’s difficult to determine whether “Shadow Ticket” is a commentary on our current era—or, anyway, more of a commentary than, say, “Gravity’s Rainbow,” which was published half a century ago.

What We’re Reading

Discover notable new fiction, nonfiction, and poetry.

This will disappoint any fans who were hoping for a rousing Pynchon riposte to our depressingly Pynchonesque era, but it’s hardly a problem. Literature has no obligation to be responsive to the times; indeed, at its best it often isn’t, which is why “timeless” is such lofty, if hackneyed, praise. But it does raise a question. If our reigning artist of paranoid convictions, of high crimes and deep states, of the peculiar combination of depravity and absurdity found in those who lust for power—if that guy hasn’t made use of the present political moment to craft a satire or a survival manual or a swan song or even an “I told you so,” then what has he come here, after a long silence and in all likelihood for the last time, to tell us?

“Shadow Ticket” is set in 1932, in the middle of the Great Depression and during the waning days of Prohibition, though no one in the book seems particularly hard up for money or booze. The first half takes place in Milwaukee, where unofficial power is divided between the Italian Mafia, spilling over from nearby Chicago, and the city’s long-standing German population, large swaths of which are falling under the spell of that ascendant political figure back in the home country, Adolf Hitler.

Our hero, however, is loyal to neither group, a fact that might be inferred from his name, Hicks McTaggart. Like Doc Sportello, in “Inherent Vice,” and Lew Basnight in “Against the Day” (who, aging but unreconstructed, makes an appearance in this new book), Hicks is that classic staple of fiction, a hardboiled detective with a softer side. A former union buster who took the “busting” part literally enough to make a lot of labor activists bleed, he is so reformed by the time we meet him that he’s vaguely Buddhist, and practically a family man: he has a girlfriend of sorts, a lounge singer named April Randazzo—the two met because Hicks, despite his slab-of-beef self-presentation, is a first-class swing dancer—and a sidekick who doubles as a surrogate son, a sweet-tempered juvenile delinquent named Skeet Wheeler. He also has a steady job, working for a detective agency called Unamalgamated Ops, where—see again that soft spot—he generally takes on the kind of two-bit clients whose desperation is inversely proportional to their ability to pay for his services.

This is a source of annoyance to Hicks’s boss, who wants to assign him to a different kind of case—or, as it’s known in the business, a ticket, so called for the paperwork that comes with accepting a job. This one involves the disappearance of the semi-scandalous young heiress Daphne Airmont, who’s the daughter of Bruno Airmont, a dairy tycoon—we’re in Wisconsin, remember?—so ruthless and felonious that he is known as the Al Capone of Cheese. Bruno himself is preëxistingly missing, having vanished some years earlier, when things started getting uncomfortably hot in the cheese underworld. Now Daphne, unhappily affianced, has run off with one Hop Wingdale, a clarinet player for a band called the Klezmopolitans, and her mother and her would-be future husband have engaged Unamalgamated Ops to bring her home.

That’s plenty of lift to get a story off the ground—but this is a Pynchon novel, so why have one reason a hero must go on a journey when you could have four? Elsewhere in Milwaukee, someone has blown up a truck belonging to a small-time booze runner, and Hicks learns that the cops plan to pin the job on him. Not long after, he discovers that April is two-timing him with a local mafioso named Don Peppino Infernacci, who is not the type to deal honorably with a romantic rival. Meanwhile, some F.B.I. agents, having concluded that Hicks is neither a Bolshevik nor a Nazi, want to hire him to serve his country, by which they might mean fighting Hitler but might also mean sabotaging the political career of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, plus anyone else “to the left of Herbert Hoover.” Should he not want the job, they pleasantly inform him, the Bureau will happily make room for him at a federal penitentiary down in Georgia.

What Hicks longs to do, in the face of these multidirectional threats to life and liberty, is persuade April to run away with him, hitchhiking from Wisconsin to who knows where, like a pair of Depression-era hoboes, out of range of anyone who wishes them ill. Instead, he reluctantly agrees to go to New York to look for Daphne, figuring a short spell out of town will cool things off. Alas, by then the cheese heiress has skipped the country, and one Mickey Finn later our gumshoe comes to consciousness aboard an eastbound ship on the Atlantic. Soon, we have swapped Milwaukee for the shattered fragments of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, from Budapest clear out to the Carpathians, as Hicks’s pursuit of Daphne slowly turns into something else: the shadow ticket of the title, a search for other things and people, one of them, two of them, six million of them, who have gone missing, or soon will.

It goes without saying that I am leaving out almost everything. As anyone who has ever written about Pynchon knows, his books are all but impossible to summarize, partly because plot, per se, seldom seems like the point and partly because of the sheer quantity of stuff going on, even in a relatively compact book like “Shadow Ticket,” which is considerably shorter than its predecessors except “The Crying of Lot 49.” Pynchon is sometimes compared to Melville, for his ambition and maximalism, and to Nabokov, for his love of wordplay and artifice, but his closest artistic kin is Hieronymus Bosch, and each of his novels is a kind of “Garden of Earthly Delights”: crammed full of figures both realistic and fantastical, many of them engaged in morally compromising behavior, all of them presumably serving some overarching but endlessly debatable organizing principle. For readers, much of the aesthetic experience of engaging with either artist involves simply attending to this profusion of details, the infinitely diverse offspring of technical excellence and an inexhaustible imagination.

Consider the character of Thessalie Wayward, a successful stage mentalist until the Depression and the talkies killed off vaudeville. Now she’s working as a secretary at Unamalgamated Ops and, off the books, for the Milwaukee police, whose officers turn to her when they fail to solve their cases by more conventional means. Her area of expertise is “ass and app”—that is, asporting and apporting, the sudden disappearance or appearance of objects seemingly from thin air, as she explains to Hicks at a lunch meeting during which she never cedes the upper hand. Although Thessalie herself basically vanishes after this four-page scene, it would be churlish to suggest that she’s superfluous, not because she paves a few linear feet of plot (Budapest turns out to be ass-and-app central) but because, like Bosch’s ice-skating platypus, she’s one of a kind and wonderfully drawn.

These lavishly created miniatures take every possible form: characters, plot devices, props, settings, scenes. There is a bar in Budapest whose variously bizarre and thuggish clientele calls to mind the “Star Wars” cantina. There is a First World War U-boat that somehow glides from underneath Lake Michigan all the way to Croatia, commandeered by its captain, post-Armistice, for new and clandestine uses. I could go on; Pynchon does, with unstoppable and quasi-manic energy. At one point, inside the diner where Hicks and Thessalie meet up, we see “lunch dramas passing like storm fronts, pies in glass cases slowly losing their a.m. allure, grill artists taking care of various counterside chores while whatever they’re flipping is in midair rotating end over end”—that’s the author, of course, staging a sly cameo for himself, confident that he can do ten things at once and still catch the omelette on its way down.

And, sometimes, he can. The first page of “Shadow Ticket” is a master class in skills many writers won’t master in a lifetime: tone, rhythm, pacing, how to establish a character, how to prime a narrative engine, how to convince your reader in six paragraphs or fewer that you know what you’re doing. Much of the rest of the book is propelled forward, or whichever direction it’s going, by long stretches of fast-paced dialogue, and Pynchon’s ear for the way people actually speak is unerring. (“Whole different tax bracket up there in Shorewood, you people, ain’t it.”) His comedic sense is considerably more fallible—“Shadow Ticket” is not the first of his novels with a sophomoric smegma joke—but, when it lands, it lands. One character has a pig for a spirit animal. Another describes the port city now known as Rijeka as “the Milwaukee of the Adriatic.” The Al Capone of Cheese, meeting the real Al Capone, asks, “And what is it you’re the Al Capone of again?”

As for pace, “Shadow Ticket” reads like one of its subplots, about the Trans-Trianon 2000, a two-thousand-kilometre motorcycle circuit through the disputed territories of Central Europe, all speed and vroom. Uncharacteristically for Pynchon, the book never eddies off to explore some branch of science or mathematics or philosophy, and the moments when it slows down enough to let the reader actually look around are few and far between—a pity, because, when he wants to, Pynchon is wonderful at showing us the world. Here is a Nazi front disguised as a bowling alley, in the outer reaches of Milwaukee, the wintry Wisconsin night lit up for miles by the sign outside: “four or five different colors from deep violet to blood orange, bowling balls flickering left to right, pins scattering, reassembling, again and again, silently except for an electrical drone fading up slowly louder the closer you get to it.”

For the duration of that sentence, Pynchon is less Bosch than Edward Hopper, making us feel this scene by making us see it: the night and the neon, the gust of loneliness, the dangerous electric edge. On the whole, though, the author is not in the business of making anyone feel things. (The shining exception to this rule is “Mason & Dixon,” the only one of his novels that is not merely brilliant but also character-driven, thematically lucid, and profoundly moving.) His customary genre is farce—the rest of his characters are subordinate to the absurd situations they find themselves in—and his customary mode is that of the comic book, full color but two-dimensional. At one point, someone hands Hicks a live bomb on the streets of Milwaukee, which he barely manages to chuck into a fishing hole on iced-over Lake Michigan before it goes kaboom; later, a pair of spies escape a near-assassination in Transylvania by climbing the mooring lines of a departing zeppelin. In both cases, you can practically see the Benday dots and speech balloons. And the emotional register of the book stays mostly within the realm of the comic book, too: the good guys are good-guy-proofed against mortal danger; the bad guys are sinister but not frightening. Even the literal Nazis are never chilling, though they are sometimes chillin’. (Over beer and bratwurst: “We’re National Socialists, ain’t it? So—we’re socializing. Try it, you might have fun.”)

For a while, all this is perfectly enjoyable—Elmore Leonard meets Stan Lee, a kind of Technicolor noir. But, the further into “Shadow Ticket” you get, the more it starts to suffer, as many of Pynchon’s later novels do, from the presence of its predecessors. Consider the cheese underworld, a sphere of criminality so consummately Pynchonesque that it reads like self-parody. In who else’s fiction would you find price-fixing on the Wisconsin Cheese Exchange, bandits invading creameries up and down America’s Cheese Corridor, innumerable nefarious purveyors of counterfeit Emmental and Gruyère?

More important: What is all this doing in this work of fiction? From the beginning, Pynchon has put his readers in the position of his characters, encouraging us to see hidden significance and obscure connections within (and, later, among) his books, and as a result to grow steadily more paranoid with each passing page. Surely, we’re supposed to think, this cheese business must mean something—maybe even, as Pynchon teases, “something more geopolitical, some grand face-off between the cheese-based or colonialist powers, basically northwest Europe, and the vast teeming cheeselessness of Asia.” Or maybe Pynchon, who nearly killed off one of the title characters of “Mason & Dixon” with a giant wheel of Gloucester, is what you might call lactose intolerant. Or maybe he just thought it would be funny to write about the big cheese of Big Cheese.

Your appetite might differ, but for me, nine novels in, all this code-cracking and jigsaw-puzzling is no longer thrilling. The same goes for the other bells and whistles of Pynchon’s style; even a seventy-million-trick pony is still a trick pony, and much of what once seemed clever in his canon now seems tiresome. You will find, in “Shadow Ticket,” countless texts within the text, including the usual LP’s worth of songs—“Midnight in Milwaukee,” “Bye-Bye to Budapest.” (“Boo, hoo, hooo-dapest,” the singer croons.) You will find golems. You will find ghosts. You will find, if you bother to investigate, real-life oddities poached from the past because they come across like pure Pynchon invention—among them Clara Rockmore, a famous theremin player (Pynchon presumably appreciates her name), and a shoe-store X-ray machine for superior fittings, which not only really existed but really was produced by a Milwaukee company. You will find the aforementioned weird forms of transportation: that appropriated U-boat, an autogiro, an enormous motorcycle built to accommodate three German sleight-of-hand artists—Schnucki, Dieter, and Heinz, who collectively sound like a Minnesota personal-injury firm. And you will find, inevitably, characters with stranger names: Dr. Swampscott Vobe, Assistant Special Agent in Charge T. P. O’Grizbee, the noted illusionist or possibly genuine article Zoltán von Kiss. (As for our nomenclaturally modest hero, Hicks McTaggart, he is presumably named for J. M. E. McTaggart, an influential British philosopher who espoused the quasi-Pynchonesque beliefs that time is an illusion and that the human soul, connected to others of its kind by love, is the fundamental unit of reality.)

This one-man-band blare never quiets, but the music darkens considerably toward the end of “Shadow Ticket.” Jew hatred spreads and intensifies, Europe becomes a place to flee, and unrest over the price of milk in the United States results in a coup in which F.D.R. is toppled and General Douglas MacArthur seizes power. Stuck in exile, Hicks takes up with a motorcycle-riding Hungarian hottie but longs for Milwaukee, where the air smells like grilled bratwurst and sounds like accordion lessons and life “seldom gets more serious than somebody stole somebody’s fish.”

By then, I longed for Milwaukee, too—for the antic early pages of “Shadow Ticket,” when something coherent seemed to be forming beneath the fun. Instead, we get a darkness that is not just moral but epistemological. A suicide in a Budapest bathroom, a secret community of people sexually attracted to tasteless lamps, a movie plot entirely about violence and overeating: this stuff isn’t Bosch; it’s bosh—absurdity for absurdity’s sake, with no discernible aesthetic or intellectual purpose.

Patches of unintelligibility are nothing new in Pynchon, but usually a coherent world view gleams upward from the murk. Modern life, in his grim estimation, is entirely controlled by capitalism and technology, forces relentlessly destructive to the human soul. Those who perceive this total control are prone to paranoia, leaving them mistrustful and lonely, while those who seek to profit from it are dragged into depravity. You can’t beat this system and you shouldn’t join it, so the only option is to somehow duck out of its range. That’s why Pynchon is drawn to drifters and dropouts, to borderlands and hidden worlds, like the Zone in “Gravity’s Rainbow,” and the interior of the hollow earth in “Mason & Dixon” and “Against the Day.”

You can see the outlines of this world view in “Shadow Ticket,” where capitalism Got Milk, the cheese is radioactive (really), and fugitives retreat to strange pockets of freedom, including a secret Indian reservation (“mentioned only once in a rider in a phantom treaty”) and that rogue U-boat (“an encapsulated volume of pre-Fascist space-time”). But the grab bag of parts—cheese barons, Nazis—never comes together, and the old obsessions never acquire new force. In Pynchon’s best works, his bleakness is brightened, in both senses—illuminated and made lighter—by the sweep of his vision and his affection for his fallible, foolhardy, well-meaning, wildly outmatched main characters. One finishes those books unclear on the particulars but certain that this whole wild world was built to teach us something, which is pretty much the human condition.

No such experience attends the completion of “Shadow Ticket.” The book ends with a letter from Skeet Wheeler, that bit player last seen a hundred and seventy-five pages ago, who writes to his former mentor to say that he’s setting off to ride the rails westward with his sweetheart, as Hicks had once longed to leave town with April. The revolt that reconfigured America goes unmentioned. If Skeet cares, he doesn’t let on; he’s just looking forward to catching the next train.

Is this act of riding off into the sunset ironic, a comment, as with “Mason & Dixon,” on the evils committed in America by the allure of westward expansion? Or is it what Hicks should have done many plot twists ago—escape the forces scheming to control him by running away with the woman he loves? Or is it just Pynchon turning around in the saddle to wave farewell? Who knows. The ticket, the shadow ticket, “Shadow Ticket”: all these remain unresolved, leaving us with the enduring hope of the Pynchon universe, that everything in it means something. At some point, though, meaning that is sufficiently cryptic becomes indistinguishable from no meaning at all. ♦