Once elected for the statutory six-year term, the longest term of any elected sheriffs in this nation, incumbents can usually count on staying as long as they please.

For most it is the last rung on their political ladder, as it was for Suffolk County Sheriff Thomas Eisenstadt, who had to end his quest for Boston mayor in 1975 after revelations he spent thousands of dollars on food and furnishings while living in the master’s house at the jail. (The service for eight of escargot servers was a real career killer.) He resigned two years later as a grand jury was considering new corruption charges.

Voters in Connecticut, which had a similar system rooted in the Colonial era, were so fed up with scandal, corruption, and patronage in their sheriff’s offices that they voted in 2000 to eliminate the posts of eight elected sheriffs and transferred their employees to a state Judicial Department. Deputy sheriffs, who serve legal papers, became state marshals.

Today in Massachusetts a Special Commission on Correctional Consolidation and Collaboration is charged with a top-to-bottom review of the county penal system and the sheriffs who run it — and it couldn’t come at a better time. Though abolishing sheriffs outright, à la Connecticut, might be too heavy a lift here, the commission seems to be eyeing an incremental approach that could impose more state control over the inefficient system of county correctional facilities.

The county correctional facilities run by those sheriffs are operating at about 50 percent of capacity, state Senator Will Brownsberger, cochair of that commission, told the editorial board.

“The mandate of the commission is to look at how we restore and reshape our facilities — state and county — and, yes, we’re allowed to consider consolidation,” he said. “It’s not foreordained. But everything’s on the table.”

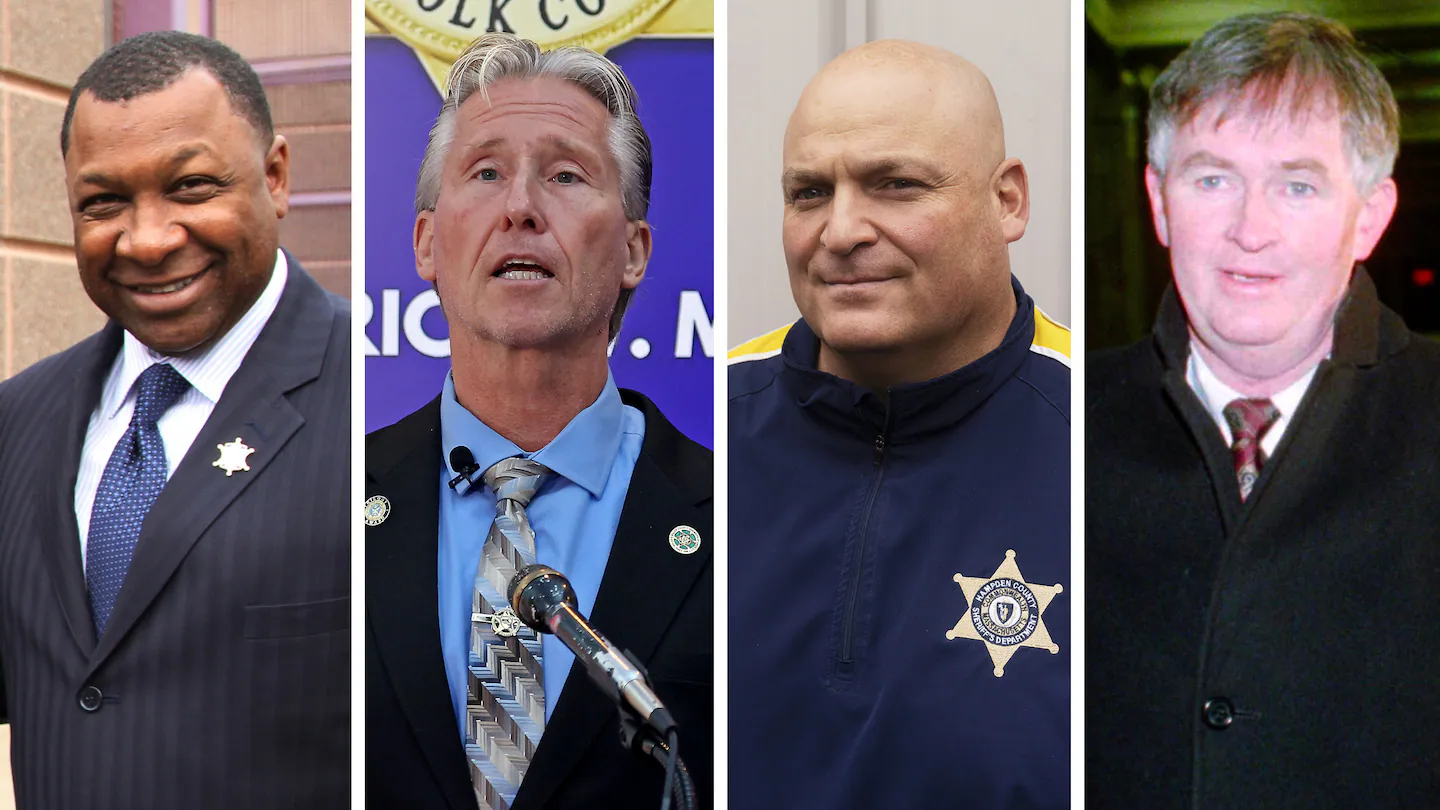

And while sheriffs have long been a politically powerful force on Beacon Hill, a string of recent scandals has left them more politically vulnerable than usual.

The Tompkins indictment on charges of abusing his office to extort a cannabis company followed several previous state ethics violations — for flashing his badge at shop owners to get them to remove his opponent’s campaign signs from their windows and later for creating a job in the department for his niece and having her and other employees do personal errands.

A recent Globe report also found that Tompkins was rarely seen at either the Suffolk County Jail or the House of Correction, both overseen by the sheriff, and that he had not swiped his access card at the jail for at least the past five months, according to records provided by the department. But he had made good use of the taxpayer-funded office credit card, including attending the annual conference of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives in Hollywood, Fla., this August, where he was arrested on the federal charges.

Hampden County Sheriff Nick Cocchi was arrested on drunken driving charges near the MGM casino in Springfield. He has been sheriff since 2017.

Middlesex County sheriffs have had their problems too. John McGonigle was sentenced to five years in federal prison in 1995 for accepting thousands of dollars in payoffs from his deputy sheriffs. He was followed shortly thereafter by James DiPaola, who resigned and subsequently died by suicide in 2010 while facing an investigation into campaign finance violations and “corrupt hiring practices.”

Breaking that unfortunate chain, Sheriff Peter Koutoujian, who was initially appointed to the job in 2011, has had a long history of being ahead of the curve on corrections trends, including using specialty units with programming for youthful offenders and military veterans. He also partnered with the Massachusetts Association for Mental Health on a Restoration Center due to open this spring, aimed at helping with from behavioral health and addiction issues.

Sorting through the good, the bad, and the ugly of county sheriffs and the facilities they run now falls to Brownsberger and his colleagues on the state commission. Others have tried and failed to reform the ancient system. A 2013 effort to consolidate several counties and eliminate sheriff’s offices (if not the actual sheriffs, which would require a constitutional amendment) failed.

Brownsberger pointed to the fact that the state Department of Correction has already closed two of its larger facilities — Cedar Junction and Concord — in response to lower incarceration rates and falling prison populations.

“The challenge at the county level is that the facilities are in different silos so that downsizing is much harder,” he said.

So many counties — using state tax dollars — continue to operate half-empty facilities.

“Now we have the opportunity to do things differently,” Brownsberger said. “Part of the trend in corrections is to try to meet the needs of different kinds of inmates” — such as youthful offenders, veterans, and those with mental health or addiction problems.

A system that really was a system instead of a collection of sheriff-dominated fiefdoms could offer those specialized services.

What is clear is that county government (which was abolished in seven of the state’s 14 counties in 1997) is an artifact of a bygone era. So too is a system of elected sheriffs, who in too many areas of the state are standing in the way of progress — that is, when they’re not standing in front of a judge.