By Lottie Twyford

Copyright abc

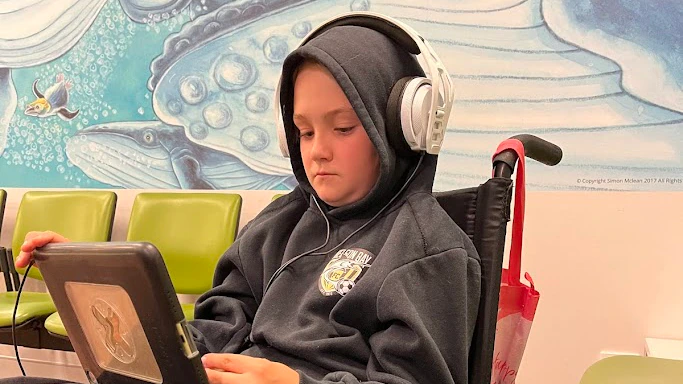

Six years ago, nine-year-old Cooper Smylie tripped and fell in the school playground.

As far as he can recall he did not draw blood or graze his knee, so he got up, dusted himself off and kept running.

Three days later, Cooper woke up with what his mum, Melinda Smylie, described as “screaming pain” in his foot.

“[It was] a burning pain … where you get real stabbing shocks,” Cooper, now 15, said.

“It just sort of doesn’t really go away ever.

It would take years of appointments and tests before Cooper, then living in Newcastle, was diagnosed with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

It was a chance meeting with an orthopaedic surgeon who walked into the wrong room that led to the diagnosis.

There has never been a clear explanation as to why Cooper developed the condition, which is caused by a malfunction in the nervous system.

“When your child’s in so much pain and there’s no clear answers, that’s really awful and heartbreaking as a parent,” Ms Smylie said.

Ms Smylie reduced her hours at work to be by Cooper’s side for many hours of occupational and speech therapy, physiotherapy and scans.

When managing appointments, homeschooling Cooper – who could no longer go to school – and caring for his younger brother got too much, she quit work and gave up her “career aspirations”.

Ms Smylie’s husband, Robert, extended his hours as a construction supervisor to make up the difference.

The family sold their home, downsizing substantially in order to be able to afford to keep up with the cost of a private paediatric pain specialist.

Ms Smylie said she would do it all again in a heartbeat, but acknowledged the financial and emotional toll.

‘A full-time job’

According to the latest survey from Chronic Pain Australia, which will publicly release its first report focused specifically on children on Monday, about 20 per cent of parents caring for a child with chronic pain resign from work entirely and 5 per cent lose their jobs.

The survey heard from 229 families across the country and found that nearly half of parents adjusted their working hours.

Thirty per cent reduced their working hours or took unpaid leave.

The advocacy group’s chair, Nicolette Ellis, said caring responsibilities disproportionately fell to women and cost, according to “conservative estimates”, as much as $15.8 billion a year in productivity.

That figure was based on an average annual wage of $50,000 and the findings of the survey.

Professor Fabrizio Carmignani from the University of Southern Queensland’s business school said other studies had shown chronic pain cost between 3 and 5 per cent of the gross domestic product per year.

“We are talking about, really, billions of dollars and a large share of these costs are effectively related to productivity loss,” he said.

Professor Carmignani said chronic pain impacted the economy at the macro and micro levels, with household budgets also under pressure from paying for medications and healthcare.

He said the cost was anticipated to grow because more people were expected to experience chronic pain over time.

Ms Ellis said finding out that 5 per cent of people reported losing their jobs due to their caring responsibilities was “really scary”.

“Many of the parents we’re talking to are saying [that] trying to navigate the healthcare system, the education system, is just completely overwhelming and becomes a full-time job,” she said.

Ms Ellis said that was particularly true given that it took three years on average to get a diagnosis, along with the difficulty of accessing services and support.

Driven to the brink

University student Eliza Lawrence, 19, has been managing chronic pain for about half a decade.

Her journey began with a knock during a soccer game and it took three years for the Brisbane teenager to be diagnosed with scoliosis and Scheurmann’s disease.

That led to her withdrawing almost entirely from school, losing friends and feeling she was not believed or understood, which severely impacted her mental health.

An admission to a complex pain program a few years ago helped enormously, but the pain has remained is something Eliza has to manage and speak up about.

“To this day there are some points in time where I can’t sit up and study,” she said.

“I’m angry and upset.”

Her mum, Kim Lawrence, said watching her daughter suffer and struggle for answers was “tedious and traumatic”.

After Eliza’s diagnosis, Kim switched to part-time work, taking a day off each week to take Eliza to her appointments.

“I had to be available to take her to those … she was so distressed,” Kim said.

“She was at a place where she was thinking about suicide and all sorts of terrible things at the age of 13 or 14.

Now studying business management and design at the University of Queensland and holding down a part-time job, Eliza is looking to the future, albeit with some trepidation about finding an inclusive workplace.

Working for the first time has proven “challenging” as the long hours on her feet can exacerbate her condition.

Eliza is also worried about being able hold down an office job because sitting for long periods can increase her pain.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that the only way I can do that is by working for myself and creating my own business,” she said.

Moving forward on the road

For the Smylies, life looks very different now than it did when they were spending all their time in hospitals looking for answers.

They have downsized even more and are in their third year of travelling the country in a caravan, seeking out warmer climates where Cooper’s pain is less severe.

“We needed to reconnect as a family, because the pain took such an emotional toll on all of us that we needed to find a way to move forward again,” Ms Smylie said.

She runs her own business from the road, which she says gives her her own sense of purpose while juggling family life and appointments.

Ms Smylie says her son’s “strength and willingness to never give up” are crucial for managing the pain he is in.

Pain medication has never helped Cooper, but he finds solace in his cat and fishing, which has also catapulted him to online fame.

“It’s kind of like my sport,” he said.

“It’s a therapeutic thing that I can just go out and [do] and relax.”