Incredible secret DNA weapon that nailed Bryan Kohberger… and how no criminal can hide again

By Editor,Rachel Sharp

Copyright dailymail

On Thanksgiving Day 2022, a DNA sample was flown 2,000 miles across the country under close guard from Idaho to Texas.

The DNA belonged to a mystery man and had been found on the clasp of a leather knife sheath inside an off-campus home in Moscow, Idaho, where four University of Idaho students had been stabbed to death. It was being hand-delivered to a lab for testing.

More than a week had passed since the November 13, 2022, murders and the killer was still at large.

Over 19,000 tips had flooded into law enforcement, but there was still no suspect on police radar. Despite the crucial piece of evidence found at the scene, the assailant’s DNA did not match anyone in existing police databases.

Just 48 hours after it landed at Othram’s forensic genetic genealogy lab, experts had determined the DNA belonged to a man whose ancestry went back multiple generations in the US, whose family derived from Pennsylvania, and who had a very specific Italian background.

Only two families in the whole of America fit that specific criteria. And among those families, there was only one man who could have been in Moscow on November 13, 2022.

Only one man who drove a white Hyundai Elantra. Only one man with bushy eyebrows who had curiously changed his car license plates from Pennsylvania to Washington five days after the murders.

That man was Bryan Kohberger.

Weeks later, Kohberger, a criminology PhD student at Washington State University, was arrested and charged with the murders of Ethan Chapin, Xana Kernodle, Madison Mogen and Kaylee Goncalves.

To the DNA experts who put a name to the damning evidence, this speed may have saved other lives, too.

‘I believe there are kids at Thanksgiving with their families this year that could have been Bryan Kohberger’s next victims,’ Kristen Mittelman, Othram’s chief development officer, told the Daily Mail.

‘And they’re not because this technology was used in real time to catch him quickly.’

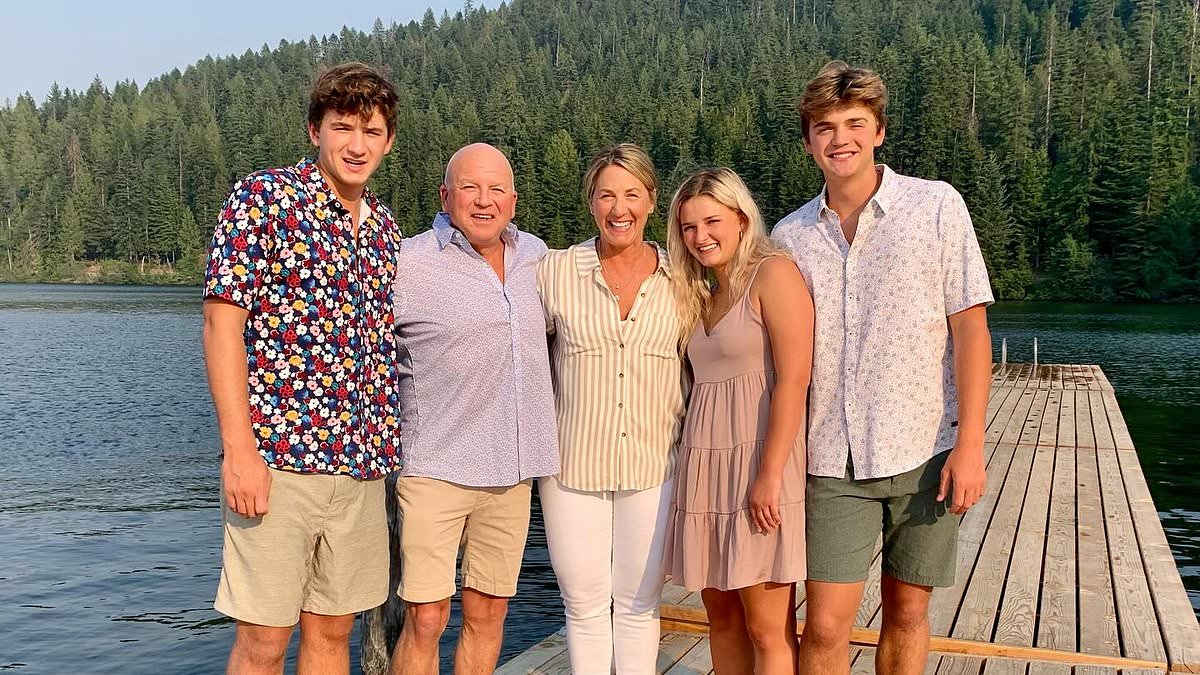

For Stacy Chapin, the 2022 holiday was bleak.

She, her husband, Jim, and Ethan’s triplet siblings, Maizie and Hunter – who were also students at the University of Idaho – had just held a memorial service in Mount Vernon, Washington, for her 20-year-old son.

‘I felt like I had nothing to give thanks for that Thanksgiving,’ she told the Daily Mail.

‘It was terrible. I was just trying to handle all of this. I didn’t want to celebrate that year.’

Stacy’s best friends rallied around, and the family stayed at home and had tacos.

She said it is touching to now know that, in that same moment, the team at Othram had given up their own Thanksgiving plans to try to catch her son’s killer.

‘It was a moment where our paths crossed,’ she said.

‘They were there crime solving… they were doing everything they could to help us, and we didn’t know that. And that’s everything to give thanks for, right?’

It was earlier that week when Idaho State Police reached out to Othram.

During the killer’s attack, he had mistakenly left his brown leather Ka-Bar knife sheath with a military seal next to Mogen’s body in her bed on the third story of 1122 King Road.

A single source male DNA was found on the button snap and had been entered into CODIS – the law enforcement database of known offenders – but there was no match.

Whoever had killed the four students in a shockingly violent stabbing spree did not appear to have committed any past crimes. Neither had any of his immediate family members.

It was a race against time to get the killer responsible for such a heinous crime off the streets.

The Othram team promised to build a DNA profile of the killer in 48 hours or less.

Othram uses a technique called forensic grade genome sequencing to take DNA from a crime scene and build a DNA profile that has hundreds of thousands of markers.

This unique, detailed profile can then be uploaded to genetic genealogical databases to search for matches to very distant relatives.

Whereas CODIS will only find a complete match to an individual, a parent or sibling, genetic genealogy can find matches stretching far back along distant branches of family trees, to narrow down the identity of the individual.

In the case of the knife sheath, there was a large amount of DNA and it was very high quality – a far better sample than the lab is often used to dealing with in cold cases.

Mittelman said the team managed to build the unique DNA profile overnight.

It was then uploaded to the databases the next morning and matches quickly emerged.

‘Very quickly, the person’s ancestry helped us narrow down who they could be,’ she said.

After figuring out the family’s location and heritage, they narrowed it down to two – one of which was the Kohberger family.

Police then used this information to contextualize the other evidence from the crime and then determined the killer.

Security footage had picked up a white Hyundai Elantra with Pennsylvania plates circling the students’ home at the time of the murders – and then speeding away moments later.

This narrowed down a suspect pool to a small number of drivers of white Hyundai Elantras with Pennsylvania plates in the state of Idaho at the time.

One of those drivers had changed his plates days after the murders.

That man’s driver’s license photo showed a then-27-year-old with bushy eyebrows – matching a description given by a surviving roommate who saw the killer leaving the home that night.

‘We’re able to be very precise. So instead of having everyone in Idaho with a white car as your suspect, you have now narrowed it down to a family, and then you can contextualize it.

‘So does anyone in this family own a white Elantra that was in Idaho that day that might have Pennsylvania plates? It’s putting all the pieces in the puzzle together,’ Mittelman said.

With the prime suspect now on the radar, Kohberger was tracked to his parents’ home in the Poconos region of Pennsylvania where he had gone that year for the holidays.

Law enforcement officers posed as garbage collectors to do a trash pull from the home.

A Q-tip in the garbage was then found to contain DNA from the father of the person whose DNA was on the sheath.

It was late at night on December 29, 2022, when the phone rang at the Chapin household in Washington.

On the other end of the line, the Moscow police officer told Stacy they had caught the man who murdered her son.

‘We had just been chasing our tails from November 13 forward. The mama bear in me was just trying to figure out how to keep my family from derailing. That had been my sole purpose,’ she said.

‘This closed a chapter. It brought us some closure. It meant we knew. We didn’t have an unknown.

‘That would have been terrible. It’s terrible to lose your kid. But it’d be terrible to lose your kid and not know who, what or why it happened to him.’

Knowing that the killer was in custody helped the Chapins move forward with their lives.

‘We had been starting to talk about putting the kids back in school but it was always: ‘What happens if that person is still out there?”

With Kohberger off the streets, Maizie and Hunter returned to Moscow for their spring semester.

But as Kohberger’s case headed to trial, his defense fought to get the genetic genealogy evidence thrown out, claiming its use was unconstitutional.

They also wanted to dismiss David Mittelman, Mittelman’s husband and Othram’s founder and CEO, from the case so he couldn’t testify as an expert witness for the state.

‘They tried everything to throw out the technology,’ Mittelman recalled. ‘But it was rock solid.’

Ada County Judge Steven Hippler dismissed the defense’s requests.

The defense also fought against the DNA evidence in other ways.

In other court filings, Kohberger’s attorneys pointed to DNA found under Mogen’s fingernails which came from three unknown individuals. They also argued that blood from two unidentified men was found at the crime scene – one on a handrail between the first and second floor and one on a glove found outside.

While Othram did not work on those profiles, as an expert in the field, Mittelman said there is a big difference between DNA being transferred between people living and spending time together, and it being on part of the murder weapon found at the crime scene.

‘DNA is very easy to transfer. There’s DNA under all of our fingernails because we all shook hands today,’ she said.

‘But what you look for as a scientist is probative DNA. We worked on DNA found on the murder weapon found at the crime scene. That’s probative.

‘The person that touched that murder weapon had something to do with that crime in that room at that time, and that is where the profile Othram built to help identify Bryan Kohberger came from. That brings certainty. That is as good as it gets for probative DNA.’

It seems the defense knew it as well.

With Kohberger’s efforts to strike the most critical evidence from his trial failing – and several other legal blows including unsuccessful attempts to take the death penalty off the table – his team sought a plea deal weeks before the trial was set to begin.

This July, Kohberger, now 30, pleaded guilty to the murders and was sentenced to life in prison with no possibility of parole.

Stacy believes her family owes a big part of this outcome to the experts at Othram.

‘It also takes all of law enforcement, too. We now have relationships within the Moscow Police Department, Idaho State Police and so on. There’s so many people we are forever indebted to.’

Without the genetic genealogy technology, Stacy believes her son’s murderer would still have been caught because of the wealth of other evidence pointing at Kohberger.

‘I want to say the case still would have been solved. It just would have taken longer.’

Though, she added, ‘I can’t speak to what [Kohberger] would have done’ in the meantime.

Mittelman believes if Kohberger hadn’t been arrested, he would likely have gone on to kill again.

‘In many cases we work, offenders are serial. You look in CODIS, and there are 50 unmatched profiles but it is the same DNA, because the same person has committed 50 crimes.

‘We need to catch people the first time, not the 50th time. If we could stop people the first time they commit a crime, we would all live in a safer world.’

Several recent cases and cold cases have finally been solved and perpetrators held to account using Othram’s advanced technology.

Murder victim Rachel Morin’s killer was identified and captured using the lab’s forensic genetic genealogy.

Gilgo Beach victim Karen Vergata was identified in 2023 – almost three decades after some of her remains were discovered.

JonBenet Ramsey’s father is now also calling for DNA from her case to be released to the lab so her killer can finally be caught.

But as it stands, Othram is not widely used by all law enforcement agencies across the country.

Mittelman said this genetic genealogy is not funded by the federal government, so police departments have limited budgets to access it for cases.

As a result, she regularly meets families whose loved one’s cases haven’t been able to benefit.

‘That’s devastating, and that’s what needs to change,’ Mittelman said.

In the Idaho four case, had Kohberger committed his crime just over the state line in Washington, law enforcement might not have enlisted the help of lab.

‘So it potentially would not have had the same outcome,’ Mittelman said.

‘I just wish we could clone what we did in this case for others.’

That’s why the Chapin family is now working with Othram to try to advocate for all law enforcement agencies to get access to this advanced technology.

When the gag order was lifted in the case, Stacy and Mittelman connected. The Chapin parents flew out to Othram’s lab to meet the team and see their work.

‘We stopped in the cafeteria and [Mittelman] said, ‘This is where we spent Thanksgiving.’ I was so incredibly touched by that story because Thanksgiving 2022 is something I’d like to just scratch out. It was our first holiday [without Ethan] – there was a void in the room.’

Stacy has since returned to the lab with her daughter Maizie.

‘We want to advocate for future victims’ families who are unfortunately going to be put in the same situation as our family,’ Stacy said.

She and Mittelman believe their paths crossed so they could work together on this.

‘Life brought us together in circumstances that are not ideal, but I believe she’s given this technology a voice and a face it needs. I hate that Stacy had to go through what she had to go through for that to happen.’

And for the Chapin family, with Ethan’s killer now behind bars and the legal proceedings finally over, Thanksgiving is something they can celebrate again this year.

‘I remember Hunter saying on that Thanksgiving, ‘We’re not having turkey!?” Chapin said with a laugh.

‘We’re back. It’s good. It’s always going to be different, but it’s okay. We’re up to a point where we have to celebrate what we have.

‘And there’s nothing of those 20 years with Ethan that I would go back and change. He was that great of a kid. He was amazing. I’m thankful to have had him for those 20 years.