‘Really angry’: Isabel is one of hundreds considering class action against this IVF provider

By Cameron Carr

Copyright sbs

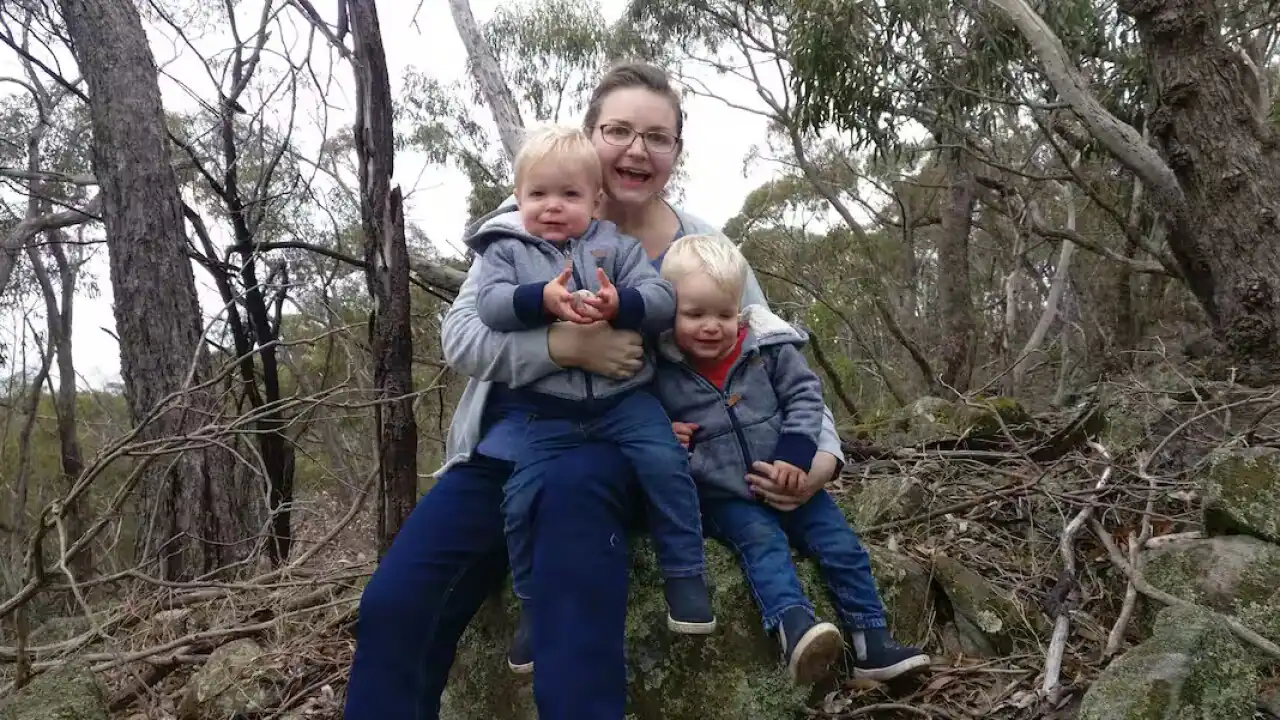

Isabel Lewis wanted to have children so badly that her friends nicknamed her “clucky”. She would write letters to the child she dreamed of having, but there was a stumbling block for Lewis. “I was 38 and single,” she tells SBS News. “It was hard to date when you are single, but you are desperate to have children.” It was then that Lewis made a big life decision: to pursue motherhood without a partner. After months of appointments and counselling, she had her first cycle of in vitro fertilisation — or IVF as it is commonly known — with a sperm donor. “In that process, I was like, 'Well, clearly then I'll be single forever. No-one will ever want to date somebody with children,'” she says. “But then I met Chris.” The pair clicked, and for her next cycle, Lewis put her initial donor on hold and used her new partner Chris Lewis's sperm instead. A few cycles later, they were trying for a fifth time, a cost that put the pair into debt. Lewis says this was going to be their last try, but to her amazement, not one but two of her embryos were successful. “We had twins, baby boys, and they're Chris's biological children,” she says. Eight years on, her boys are happy and healthy, and she and Chris are married. The now 46-year-old holds her journey to motherhood close to her chest, but since a data breach targeted the fertility clinic she used, she's become concerned it could be exploited for malicious purposes. In February, Genea Fertility informed clients, including Lewis, via email that personal data had been breached by cybercriminals and posted to the dark web. The exposed data includes the medical histories, diagnoses, treatments, and prescription medications of those clients, as well as pathology and diagnostic test results. In July, the clinic confirmed it had concluded its investigation and was “starting to communicate directly with individuals about the findings … relevant to them”. It's been hard for Lewis to come to terms with the data breach. “This is how I built my family. It's so deeply emotional and deeply personal. It's our family story. And to have it on the dark web? How do you even process that?” she says. Genea has created a page on its website to communicate updates with impacted clients. “We thank our community for their patience and understanding during our investigation into this cyber incident. We deeply regret that personal information was accessed and published and sincerely apologise for any concern this incident may have caused,” Genea's website reads. “The protection of our patients, staff and partners' information remains our utmost priority.” Lewis says the data breach has shaken her confidence in the industry, and some of Genea's other clients appear to feel the same way. SBS News has contacted dozens of people who claim to be victims of the Genea data breach. While a few agreed to speak anonymously, Lewis was happy to talk openly about her experience with the clinic. Her candour and good humour are striking. She recounts everything from the discomfort of invasive procedures to the financial toll of multiple rounds of IVF, each costing around $10,000. “The fertility treatment is probably the most invasive and emotional medical treatment you can have,” she says. “I've had treatment for mental health stuff, and I'd probably be less concerned about that being on the dark web.” “You have an internal ultrasound on the third day of your period, which is not something any woman wants to go through, let alone have a report about it on the dark web,” Lewis says. When asked if Genea's apologies for the breach go far enough to make amends, her voice takes on a new tone. “I'm rageful, which I laugh about because that's a protection mechanism,” she says. “I want new legislation and IT fines that are proportionate to the company's size and financial capacity and the size and impact of the breach,” Lewis says. Lewis has signed on to a class action investigation being conducted by specialist litigation law firm Phi Finney McDonald. She feels it's too late to reclaim her privacy, so seeking justice through a class action is “all she can do”. The firm's principal lawyer, Tania Noonan, confirmed the group is looking into “potential redress” for those impacted by the breach. “Patients at Genea are entitled to the highest levels of privacy and safety to ensure their personal details and medical histories remain secure,” Noonan says. SBS News understands hundreds of people have contacted the firm in relation to the Genea data breach, along with Lewis. “I think change comes from remittance,” she says. “I'm not doing it for the money, although money is fine and all, but if there are damages that are significantly painful, hopefully — and maybe I'm deluded — the business will change their practices so that they don't have damages like that again.” Australia's IVF sector has been subject to intense scrutiny following a series of high-profile incidents and systemic failures that have prompted calls for reform. Earlier this year, Monash IVF disclosed it had transferred the wrong embryo to a patient, two months after a patient was mistakenly implanted with another client's embryo, prompting its CEO to step down. Family creation lawyer Sarah Jefford says it's time to look at how the fertility industry is regulated. “The fertility industry is in a place where there's a lack of community trust and particularly when we have had a tumultuous few years with fertility,” she says. Jefford explains that the fertility industry is essentially self-regulated, with “patchwork” laws in each state and territory around assisted reproductive treatment. “They don't really have clear legislation on regulating their day-to-day practices of fertility treatment,” she says. “That's worked really well up until a point, but I think now we need to look at a different framework to really bring it into line with community expectations about what we expect from the fertility industry.” She echoes Lewis's sentiment that a financial penalty could lead to a change in how fertility clinics operate. “I know that the fertility industry is worth over $700 million a year. I do think that money talks, so perhaps a financial incentive or penalty could make change in the industry that's otherwise not very well regulated,” Jefford says. “It may not be about getting financial compensation … but it should set that standard for fertility clinics to know that this is protected information, and they need to be very careful about what they do with it.” In Australia, the annual revenue from the fertility and IVF industry exceeds $800 million. David Vaile, former chair of the Australian Privacy Foundation, says Australia doesn't have a “vigorous privacy data protection litigation process”. Until recently, the Privacy Act didn't include provisions for Australians to sue to enforce their rights after a privacy breach. But in February, a landmark reform took effect, allowing individuals to pursue civil action for significant breaches of personal privacy. Vaile says a class action against Genea could be the first and perhaps soon-to-be-famous test of the new privacy tort. It may well be that it'll only be through something like a class action that would justify enough legal effort being put into that to actually test [the news laws] out,” he says. If successful, a class action of this kind could compel Genea to pay millions in damages to impacted clients of the data breach, and air allegations in court regarding the company's conduct. Class actions differ from other types of lawsuits, as they involve seven or more persons with claims against the same defendant. A class action against Genea could also fall under several types of law, such as consumer, human rights and health law, and its scope would be determined by the law firm working on the case in consultation with the plaintiffs. Previous consumer law class actions have addressed losses resulting from scams and unfair business practices. Human rights class actions have investigated alleged abuses and breaches of human rights, such as an individual's right to privacy. Medical class actions have typically addressed defective operations and treatments. Vaile says it will be interesting to see how a legal firm tackles a class action relating to IVF data. He suggests one approach could be to apply equity law to the medical sector. “Equity isn't about whether you have breached this law or that law, but [asking] 'is your relationship with these people [the patients] so special that you have a special obligation to them?'” he says. “When there's a vulnerable patient who doesn't really have much choice and a very powerful professional — whether a nurse or doctor in a position of power over them — that creates what's known as an equitable obligation. So, if there are confidential matters, like medical history, involved, that could be relevant.” After discovering she'd been affected by the data breach, Lewis has been troubled by a niggling question. Why, eight years after the birth of her children, did Genea keep her data? “I understand that my medical information and success rate can be useful for the clinic and other women, but why do my name and personal details need to be attached to it? They could have de-identified me,” she says. SBS News put this question to the fertility group, and a Genea spokesperson said maintaining patient records is mandated by law. “The regulations that govern healthcare operations in Australia and other legal requirements mandate that we maintain patient records for certain time frames,” the spokesperson said. “There are also additional record retention requirements that depend on variables such as type of treatment, the outcome of the treatment and the state or territory in which the services were provided.” While data retention policies vary state by state, Vaile says groups that retain data have a responsibility to protect it. However, it can be nearly impossible to totally prevent malicious actors from hacking data, so the best thing to do is to decrease what can be stolen. One way can be through data minimisation, where companies reduce the amount of data they store. Vaile says a common school of thought is that data is a “toxic asset”. “The more you have of it, the higher the risk. The longer you hold it, the longer the data retention period; the higher the risk. The more intensively you use it and enable access to it, the higher the risk,” he says. Vaile says if a class action found that health workers have a “special equitable obligation” to patients, it could make the entire medical profession “go nuts”, adding that the way Genea stores clients' data could be a key factor in potential future litigation. Advocates have been calling for reform in the IVF sector and for the establishment of a national regulator or watchdog. “It's time that we had an Australian Assisted Reproductive Commission that could actually regulate the entire fertility industry, including donor conception and surrogacy,” Jefford says. “Their job could be setting standards for fertility treatments, fertility clinics and licencing and making sure that there is accountability for fertility treatment in Australia, as well as keeping records for donor treatment and surrogacy to make sure that people have access to information about their conception and birth heritage.” Evie Kendal, a bioethicist and public health scientist at Swinburne University of Technology, says the checks and balances for the IVF industry aren't up to standard. “If we are in a situation where people are having the incorrect embryo transferred, then something has clearly gone wrong,” she tells SBS News. “And because the stakes are so high when it comes to making families, we really can't afford to have any errors, or we need to make sure we have as few as humanly possible.” Not only could regulatory reform lead to better health outcomes and data security, but it could also rebuild trust in the IVF sector, Kendal says. “We are seeing mistakes and human errors that are actually having massive ramifications for families. An independent watchdog or a federal regulatory body would actually bring back a lot of trust with the community,” she says. “The fact that we have inconsistent state legislation when it comes to assisted reproduction and the fact that the rules are different depending on where you are in the country really does undermine that public trust.” A federal watchdog could also regulate how much profit an IVF clinic is allowed to make for its services, Kendal says. Earlier this month, federal Health Minister Mark Butler announced the establishment of an independent accreditation system for fertility providers. Accreditation for services will be provided by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care and will be in place by January 2027. The body would develop nationwide guidelines, performance monitoring metrics, workforce and staffing guidance and clearer complaint pathways. However, the government has not committed to legal reform or national laws regulating the industry. Lewis is hopeful the class action could lead to changes in the “lucrative” IVF space and make it a better and more secure process for Australians wanting to start a family. “For some people wanting to have kids, the level of desperation and the money that has gone into it is staggering. “There needs to be something in place to protect people, and there have to be some serious consequences for commercial organisations not taking that responsibility seriously.” download our app subscribe to our newsletter