By Bhanuj Kappal,Ojas Kolvankar,Sarang Gupta

Copyright gqindia

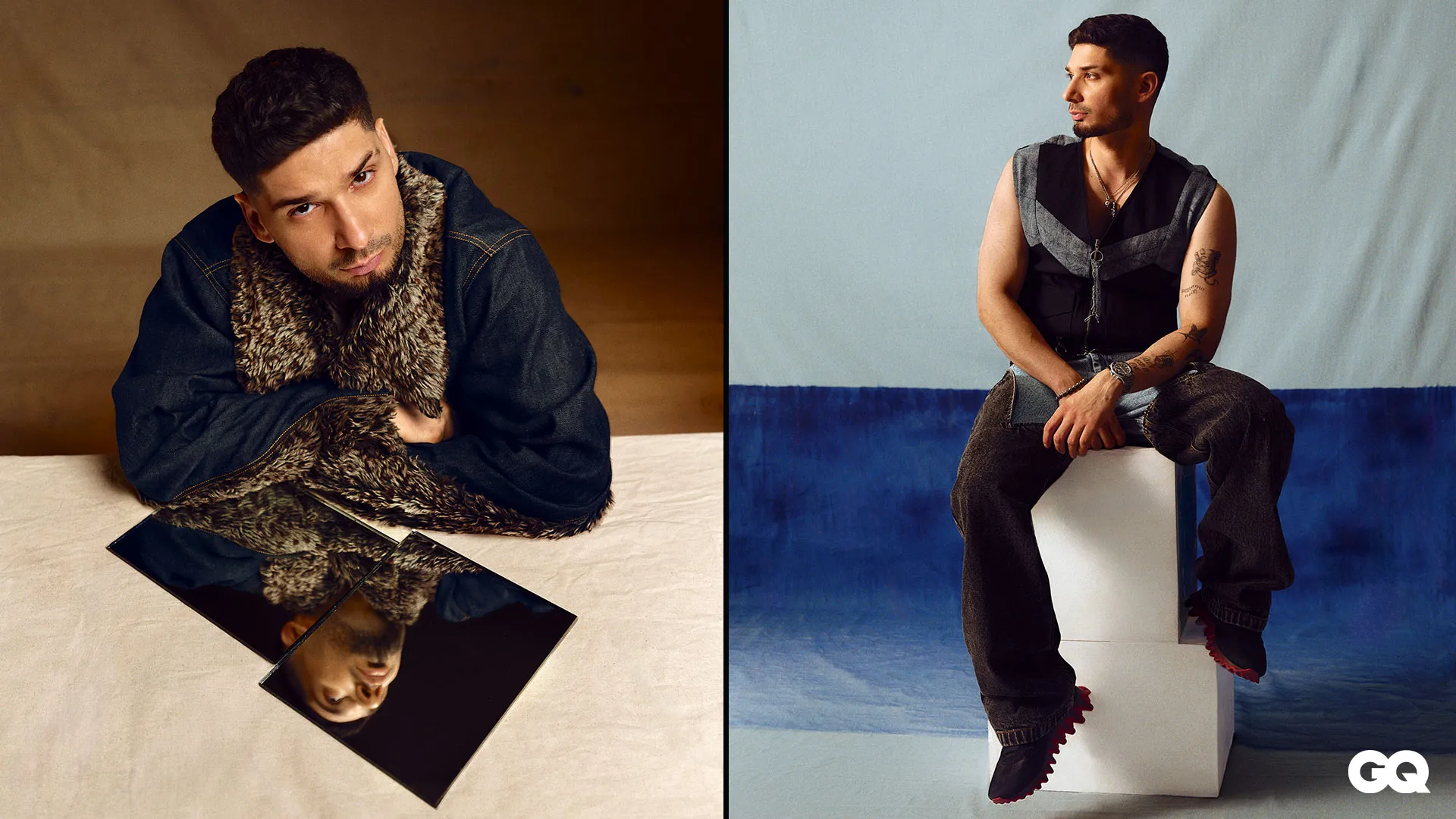

Most artists would have tapped out long ago. But Kr$na is still here—still writing, still rapping. He’s played the long game, soaking up each insult and betrayal, using it as fuel for the fire. And over the last few years, that persistence has finally started to pay off.

His latest mixtape, Yours Truly (released on his childhood icon Nas’s Mass Appeal label), hit #1 on Apple Music -within 12 hours of release and crossed over a million streams on Spotify within 24 hours. He’s collaborated with local heavyweights like Badshah and Raftaar, as well as global stars such as Awich, Jay Park and Tech N9ne. He’s been ranked #10 on Lifted Asia’s list of the hottest rappers in the region, and he’s rocking festival stages from Mumbai to Phnom Penh. It’s a -hard earned victory lap for the kid who never quite belonged, but never stopped showing up.

“Honestly, I just love what I do,” the 37-year-old shrugs when I ask him what kept him going through the lean years. “Even when I tried to quit rap, the universe kept pulling me back in. So I figured that I’m just meant to do this.”

Krishna Kaul grew up in a Kashmiri Pandit household in the national capital, the only child of parents who ran a small PR agency. Like many other single kids, he kept to himself, preferring the world of his imagination to the company of his peers. “I pretty much lived inside my head. I was an only child, and I was always a little quiet. I tended to observe more than speak. I think I’m still like that.”

Kr$na credits his love for language to his grandfather, a former ONGC -employee who published several short stories in Koshur. When his parents were busy at work, he’d hang out at his grandfather’s mezzanine office in Connaught Place, a tiny space that always smelled of fresh newsprint. That’s where Kr$na nurtured his love for reading, voraciously devouring everything he could get his hands on: newspapers, magazines, take-out menus—anything with type.

“A lot of people ask me now, how do you know all these things you put in your -music?” he says, referring to his penchant for hyper-referential wordplay and -esoteric puns. “It’s just absorbed through years of reading all kinds of rubbish.”

Kr$na was first introduced to hip-hop music by an uncle from Kashmir who would play songs by MC Hammer and Public Enemy whenever he visited. But he only really started paying serious attention after the family moved to London when he was 10 years old. As a stranger in a strange land, rap music became a means of survival, a way to navigate the complicated class and racial politics of a South London state school. “I felt like I was just thrown in the deep end. I suddenly had no friends, and I found myself in an environment that felt actively hostile,” he remembers.

His school was a battleground, with regular incidents of gang violence. Sometimes, kids would bring guns to school to intimidate or threaten their rivals; other times, kids would fight each other with fists and knives. He remembers watching one boy get stabbed on the school football ground, blood dripping all over his hands and jeans. “It was like kill or be killed. You either had some sort of persona that gave you cred, or you’re just getting bullied.”

Getting into rap, then, was a strategy for self-defence as much as an outlet for what he was feeling. Kr$na started writing rap lyrics when he was 14, uploading battle bars as text or audio clips in online communities. Eventually, a few of the other school kids, who were already rapping on local pirate radio, figured out who he was and invited him into the fold. He was a bit of a novelty, “the Indian kid who rapped”. But he had enough street cred for the -bullies to leave him alone.

He soon immersed himself in the music and culture, not just as a listener but also as a student. A scholar, even. “There was a time when you could ask me about any rapper and I’d know who they were, what albums they’d put out. I was obsessed,” he says. Kr$na may no longer be a walking rap encyclopedia, but that obsession still burns bright. And especially when it comes to younger Indian rappers, who, in his opinion, aren’t doing their homework. “I feel like a lot of them grew up listening to us, but they aren’t digging deeper,” he elaborates. “They might listen to me or Seedhe Maut or Divine, but they don’t ask where this music is coming from. What are the yeses and noes? What are the sensiti-vities of the culture?”

Having gotten his start in the battle rap scene, he naturally gravitated towards punchline-heavy MCs like Lloyd Banks, Big L, Fabolous and Jadakiss. Even more than the tongue-twisting wordplay, he was drawn to the aggression of it and the opportunity to plainly speak his mind, with no need for subtext or navel-gazing poetic allusion. “It’s a really liberating feeling to be able to say the craziest shit and have it be brushed off because it’s just a battle. It gave me the confidence to say exactly what I felt.”

By the time the family moved back to -Delhi after five years in the UK—“because life was just easier back home”—he was so deeply embedded in hip-hop culture that he was yet again the odd one out in his school. It was only during his undergrad years at Delhi’s Hansraj College that he found a couple of other friends who were into rap.

They quickly crewed up, calling themselves Illicit Cash Mob. The three would pool their pocket money to record in local studios, rapping over pre-selected beats and leaving with CD-R discs full of demo songs that they’d pass around college. He’d spend his nights at different hip-hop clubs across the city, where he made friends with all the DJs. They’d allow him to jump on the mic, and he’d freestyle like an old-school emcee.

In 2008, he moved to Mumbai to study public relations at the Xavier Institute of Communications and started to wonder if he could turn this rap thing into a -legit career. The songs he was putting out—under the Young Prozpekt moniker—had begun to generate a little bit of buzz in the very-nascent Indian rap scene, being passed around on MySpace and via Bluetooth like some secret talisman. A hip-hop producer friend from Delhi had also moved to the city, and he’d spend hours at this friend’s home studio, writing and recording. He’d also started reaching out to underground rappers in other countries, scoring some of Indian rap’s earliest international collabs—including a 2007 -feature from Bay Area rapper Soldier Hard, a member of Baby Bash’s crew, for “I Go Go”.

One day in 2009, Kr$na worked up the courage to go to the Universal Music India offices and hand a four-track demo to one of the A&R guys, who promptly ghosted him. He kept following up until the guy finally responded. “He told me that my music sounds too international for India, it won’t work out,” Kr$na remembers, still seeming -a little dumbfounded by the response. “That was really bizarre. What do you mean it sounds too international? That’s a fucking compliment, but you’re saying it like an insult.”

Instead of being dejected, Kr$na deci-ded that he needed to understand how the music label ecosystem worked. He started applying for internships, eventually getting offered one by—you guessed it—Universal Music. “Once I started working there, I understood that there was no criteria. There was no method, there was no merit. There was nothing. It was just some nonsense about who knew who,” he says.

RAP AS RESISTANCE

In 2010, Kr$na had his first real viral -moment with Kaisa Mera Desh, a protest song that took aim at the corruption scandals plaguing the Commonwealth Games in Delhi. This turn in his sound was -inspired by hip-hop’s politically conscious roots, but also by the then-bubbling Iranian rap underground, whose artists were risking the death penalty by critiq-uing the regime. (Not much has changed on that front, as shown by the recent case of Iranian rapper Tataloo, sentenced to death for blasphemy this May.)

Kaisa Mera Desh became an unlikely sensation, ranking alongside MC Kash’s “I Protest (Remembrance)” as one of the biggest protest songs of the early desi rap years. He was interviewed by every major newspaper, and his song was on the news. “That really gave me a lot of confidence and motivation,” he says. “Suddenly, it wasn’t so crazy to imagine that one day I could make a living rapping, you know?”

Kr$na spent three to four years focusing on politically conscious rap, releasing another anti-corruption anthem (The Lokpal Freestyle) and a track about child labour (Vijay). But he was a little too -early. Protest rap didn’t have a real consti-tuency in India yet, and once the -headlines moved on from the CWG scam, so did the press’s attention from the genre. More imp-ortantly, it just wasn’t going to pay the bills, especially once he quit his job with Universal to focus on music full-time.

He gave up on his rap dream, moved back to Delhi and accepted an offer for a digital marketing job for a Singapore firm. But just before he was due to leave the country, he got a call from an old colleague at Universal Music. They were launching a new property called Contrabands, in collaboration with VH1 and Hard Rock Cafe, and wanted to know if he would like to record an album for them. The catch? He only had a month to put it together. “It’s probably the release I’m least satisfied with in my life,” he says. “But I needed something at that point, so I had to do it. I had no choice.”

He changed his name to Krsna (the -dollar sign came later) because he felt like the more pop-oriented songs he was doing didn’t do justice to his work as Young Prozpekt. He called the album Sellout, ostensibly to deflect criticism from his underground peers for signing with a major label. But maybe, subconsciously, because of a little bit of discomfort with the project. The first single Last Night—–a frothy, unremarkable piece of club-rap—did well, hitting #5 on the VH1 music charts in India, and he got to do his first multi-city tour to support the project. Things were looking good. And then it all fell apart. Again.

Universal refused to sanction a music video for a follow-up single, so he used his advance to pay for it himself. When he delivered the video to the label, they came back with a ₹10,000 marketing plan. “That was all they were willing to spend. I felt like a fool. And then I was just so jaded by that whole experience that I quit.”

He was at his lowest. He was depressed and even had suicidal thoughts. (Kr$na references these thoughts on the heartwrenching title track of his recent -mixtape Yours Truly, which takes the form of a searingly honest letter to his younger selves.) He didn’t write any new music for two years; then serendipity struck again. A school friend who had just returned from the US, flush with capital, convinced him to start a record label together. He drew on his experience at Universal to come up with a business plan—the label would act as a funnel, finding talented artists, building them up, and eventually striking -distribution deals with -bigger labels.

“But I couldn’t convince anyone to sign with me, so we needed to put out a track as a demonstration. We needed to show that the business model worked; we needed a guinea pig. And since there was nobody else, I figured I’d be the guinea pig.”

Kr$na spent a month writing his comeback song Vyanjan, a stunning display of linguistic and alliterative virtuosity, each bar consisting of words from a different letter of the Hindi alphabet. The song popped and caught the attention of Ankit Khanna, who signed him on for his new label Kalamkaar (cofounded with rapper and music producer Raftaar) in 2017. “I made that [business] plan work so well that there was nobody to run the model anymore. So it was kind of funny,” he laughs.

By then, Divine, Naezy and the Mumbai rap scene had exploded into the mainstream. How did it feel watching rappers who started much later than him -strutting in the spotlight? “I was very happy for them. The only thing I felt bad about was putting in so much work and getting nothing out of it. I had come close so many times since 2010, but I was still so far.”

He knew this was his last time on the merry-go-round; he didn’t have it in him to rebuild one more time. But he was -older, wiser and more patient. And in Khanna and Raftaar, he had people who really believed in him. By 2019, he’d found his stride, and his sound—dense referen-ces, razor-sharp lyricism and ice-cold flows.

When rapper Emiway Bantai put out a song claiming to be the only rapper representing India, Kr$na felt like he was ready to stand up and be counted. His song Freeverse Feast (Langar)—-a diss aimed at Emiway—ignited a red-hot beef that lit up the desi hip-hop scene. When New Delhi rapper Muhfaad took shots at -Raftaar and Kalamkaar a year later, -Kr$na hit back. The two traded diss after diss, and Kr$na walked away the clear winner. His track Makasam, a brutal-yet–virtuosic evisceration of Muhfaad, is widely -considered one of the best disses to come out of India.

It also established Kr$na as among the most -accomplished lyrical rappers in the country. “I started out in battle rap, this is what I trained for,” he says, before adding that he’s over rap beef now. “I got into it because I feel competition is a very integral part of who we are as MCs; it’s an integral part of hip-hop. But I moved away from it because that’s not entirely who I am.”

The beefs also supercharged his fandom, who started calling themselves “awaam”, taken from “Teri Praja Nahin, Yeh Meri Awaam Hai”—lyrics from his 2020 single Maharani—and developed a cult-ish devotion for their favourite rapper. Kr$na remembers fans erupting in tears on meeting him, an experience which -always leaves him feeling humbled and a little bemused. He’s wary of letting the attention get to his head, but the awaam train has only gathered more steam in the years since, with the fans rocking “Awaam till the end” T-shirts at his gigs, and still fighting running battles on social media with fans of rappers he’s beefed with.

CRACKING THE CODE

His sophomore album, 2021’s Still Here, was a triumphant return-to-form, proving that he could rack up numbers just as fast as he could rack up double and triple entendres. But Kr$na is never one to rest on his laurels, so he followed it up with a run of three very different EPs and a bunch more singles, experimenting with trap and drill sounds, and collaborating with artists from around the world and across the musical landscape. All these forays into new sounds and styles bear fruit on Yours Truly. The tracks on the mixtape veer all over the place, -ranging from classic flex bars (Knock Knock) and socio-politically conscious rap (Sensitive featuring Seedhe Maut) to the hauntingly pensive and introspective title track. What unites them into a cohe-rent work is a bunch of skits samp-led from a 2015 episode of the erstwhile rap -podcast Voice Of Tha People, in which hosts and rappers Enkore and Bobkat -dissect -Kr$na’s career and wonder why he hasn’t yet received his flowers.

“They were voicing things I couldn’t say about myself—my grievances with the industry, how people had treated me,” he recalls. “I was in this weird purgatory. The underground didn’t want to give me my props because I was not at the cyphers anymore. I’d already done that before these guys even started. And I was never an all-out commercial rapper, so I didn’t fit in there either. I really felt alienated, and those skits validated how I felt.”

Yours Truly, then, feels like a culmination: Kr$na clearing the board and putting old ghosts to rest before launching into a new phase of his career—one where he’s not an outsider looking in, but an acknowledged master of his craft. He feels ready to try new things, write about new ideas and experiences, maybe start work on a new album (though maybe he’ll put out some singles first, he says). He’s even taken up golf, vlogging about his journey with Scarface’s favourite sport on a new YouTube channel called Dollar Sign Golfing.

As we wrap things up, I ask him if he still sometimes feels like he’s stuck in purgatory. “Not anymore. That changed when my music started popping, because it was such a fresh start. There were so many new fans who had no idea about this background or history. And at that point, your little eight–person underground scene cartel doesn’t matter. You know, they’re not going to influence anything anymore,” Kr$na says.

Head of Editorial Content: Che Kurrien

Hair & Make-up: Anuradha Raman

Art Director: Mihir Shah

Entertainment Director: Megha Mehta

Senior Entertainment Editor: Rebecca Gonsalves

Visuals Editor: Shubhra Shukla

Production: Nafromax Productions

Fashion assistant: Vedica Vora