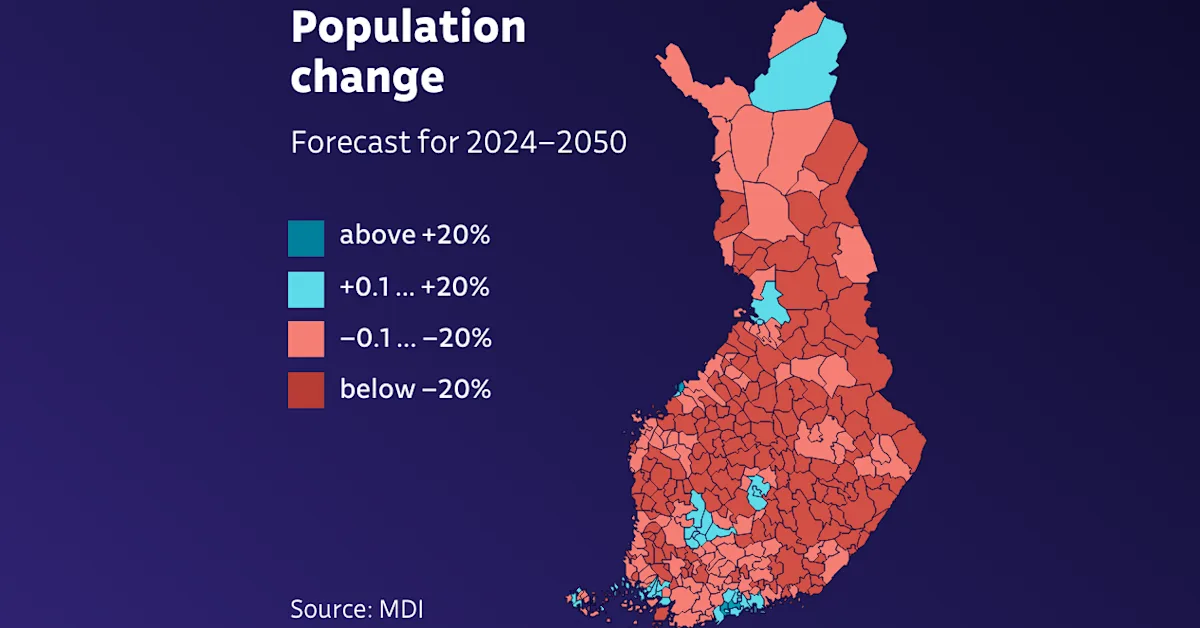

According to a new population forecast for Finland that was published on Tuesday, the vast majority of municipalities are set to shrink rapidly.

The consulting firm MDI’s forecast for the next quarter century paints a bleak image. Previously, forecasts have only been made until the year 2040, but the new outlook goes a decade further.

The overall picture can be seen in the interactive graphic below. Readers can check the situation across various areas by entering the municipality’s name.

Finland has struggled with how to deal with its ageing population for some time, as the number of births in the country has continued to fall.

But there is a new development in the trends, as population numbers threaten to head into negative territory in many smaller cities, including Kuopio, Joensuu, Vaasa and Rovaniemi. Until recently, those areas were still growing as people from even smaller municipalities moved in.

Those cities are now shrinking because more people are dying than being born, and the trend appears to be permanent — a shift that began in 2016.

Immigration helped, but will it last?

The number of people who move to Finland from abroad has largely filled the gap and prevented population decline. But soon, according to the firm’s forecast, immigration will not be enough to fill those gaps, especially if the number of Ukrainians seeking shelter in Finland comes to its presumably eventual end.

“Previously, higher mortality was always a temporary exception, such as during the civil war or years of famine. But in 2016, we moved into a state where Finland’s population is decreasing every year without immigration,” said Rasmus Aro, the leading expert at MDI who prepared the forecast.

Many people might think that the relatively high death rate is limited to small municipalities, but that is not the case. According to the forecast, Finland already appears to be a largely dying country.

Aro noted that only one in ten municipalities sees more births than deaths, saying that “even in many of those, the difference is very small”.

The very few exceptions to this trend are Finland’s largest cities and a few of their surrounding municipalities. Another regional exception can be seen in some parts of Western Finland — sometimes referred to as the country’s ‘Bible Belt’ where religion plays a comparatively major role in society.

According to the forecast, there will be 96,000 fewer children attending schools in Finland by the year 2032.

“A hundred thousand pupils’ school desks will be vacant within a very short time,” Aro said.

He said that the number of children in schools will decrease in almost all Finnish municipalities during this decade.

The bleakest development will hit around 100 municipalities, where the number of schoolchildren is expected to fall by one-third by the early 2030s. In contrast, only a handful of other municipalities will see an increase in pupils.

Aro said the development will be reflected in the closure of “a lot of schools”.

At the same time, according to the forecast, the number of people over the age of 84 will increase by 142,000 by the year 2040 and by 174,000 ten years later.

According to Aro, that is one of the key findings in its forecast. Finland’s ageing population — and related increases involved in their care — is not a temporary phenomenon, but rather one which will continue until the 2050s.

According to MDI’s forecast, Finland’s population will not be able to exceed six million as things currently stand. Instead, the population will begin to decline in the 2040s.

Success in Lapland, despite trend

However, there may be hope, according to Aro, who pointed to population changes in Finnish Lapland.

A tourism boom prompted a deluge of money and jobs in the region, and now its future does not look as bleak as in other areas, including Eastern and Central Finland.

Aro said that Lapland is a great example of how trends can be influenced and reversed, despite shrinking population projections.

During the Covid era, many people hoped that the burgeoning remote working culture would enable people to move to more remote areas, according to Aro.

But that trend has subsided considerably, and people are again turning to larger growth centres, he explained.

“Population concentrations have been quite rigid since the 1960s. I find it rather unlikely there will be any significant changes [to the broader trend], at least in the medium term,” Aro said.

According to Aro, if Finland wants to maintain a growing working-age population and economy, the only alternative appears to be immigration, which he acknowledged is a controversial idea to some.