Joe Hickerson, folk musician and lead archivist of folk music at the Library of Congress, dies at 89

It was at a leftist summer camp in the Catskills that Joe Hickerson came up with the final two verses to Pete Seeger’s popular song “Where Have All the Flowers Gone.” The new verses turned the song into a cyclical ballad that drove home its anti-war message.

“He was so proud of that, it was actually on his business card,” said Stephen Winick, folklife specialist at the Library of Congress.

Hickerson enjoyed a long career as a folk musician and archivist of folk music at the Library of Congress. He died on August 17th at the age of 89. The cause of death was congestive heart failure.

He was born in Lake Forest, Illinois in 1935, and grew up in New Haven, Connecticut, the youngest of two boys. His father, James Allen Hickerson, was a professor of math education at New Haven State Teachers College. His mother, Elizabeth (née Hogg) worked in the student records office at Yale University.

Hickerson came by his love of music honestly. His maternal great grandfather, John R. Sweney, authored over 1,000 gospel hymn songs. His older brother became a professional pianist. “From the very beginning, his family played music at the piano and sang,” said his son, Michael Hickerson. “They would listen to the radio a lot. Music was part of the air they breathed.”

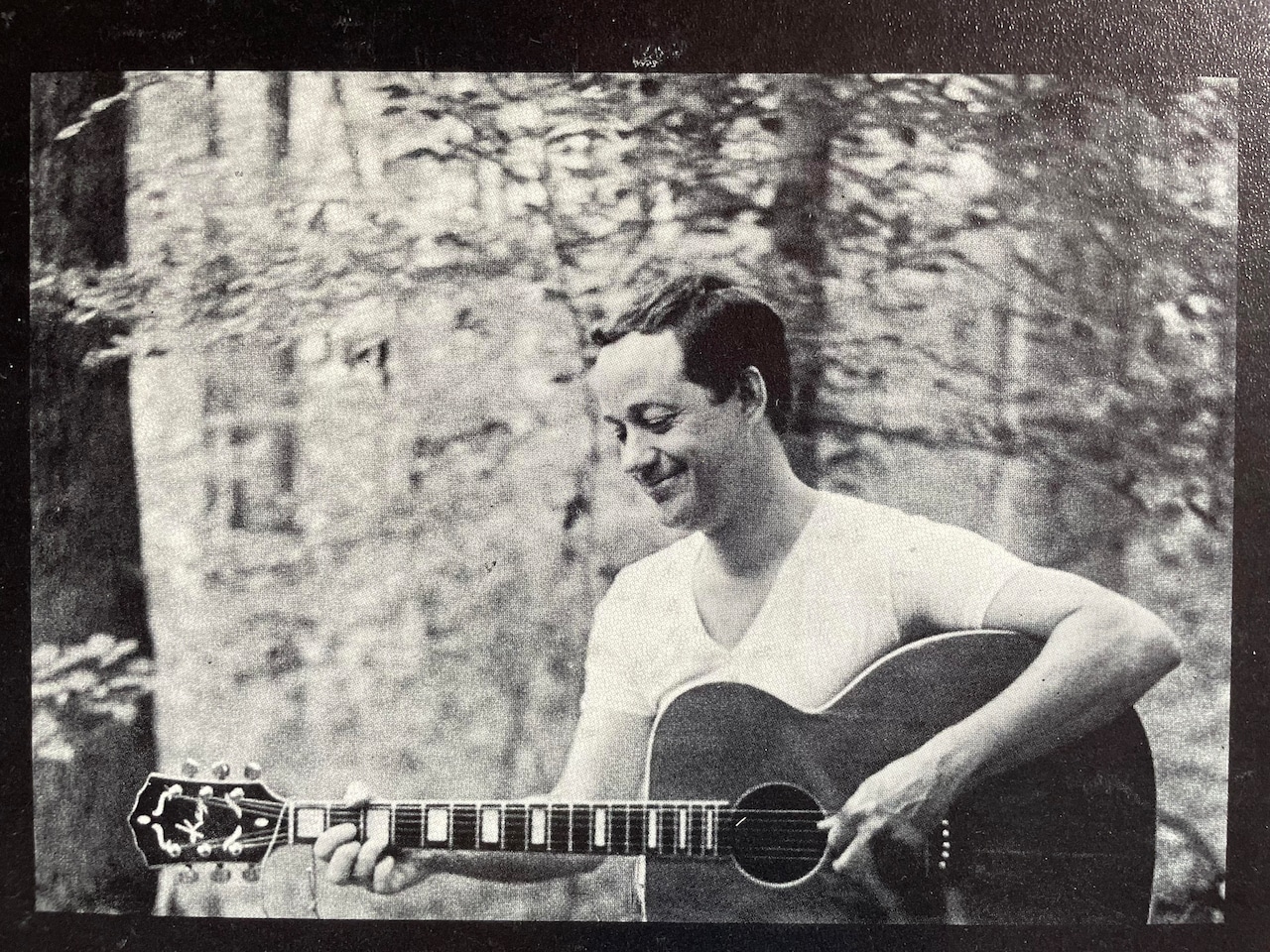

The first instrument Hickerson picked up was the ukelele, which he would practice in his home’s attic. Then he transitioned into the guitar, which he played left-handed.

As a boy, Hickerson fell in love with folk music. The first single he purchased was “(Ghost) Riders in the Sky: A Cowboy Legend,” sung by Vaugn Monroe.

Hickerson’s penchant for music archival work bloomed early in his life. On graph paper he borrowed from his father, he charted the top hits. “He plotted the data from week to week on a big scroll. Each line was a song that rose and fell with the ranking of the popularity,” Michael Hickerson said.

Hickerson attended Wilbur Cross High School and sold ice cream from a Good Humor bike as a teenager.

He dreamed of becoming an astronaut, so after enrolling at Oberlin College, he decided to study physics. “He was really into space science and astrophysics,” Michael Hickerson said.

While in college, Hickerson served as the first president of the Oberlin Folk Song Club. He formed a band called the Folksmiths, who released the first commercial recording of the song “Kumbaya.”

In 1957, he began pursuing a PhD at Indiana University. There was tension between him and his mentor, Professor Richard Dorson. “Dorson was a very well-regarded scholar in folklore,” Michael Hickerson said. “He did not believe that scholars should actually take a part in folklore. He frowned on my dad performing. My dad started out as a scholar, but always had his guitar in his hand. It may have been one of the reasons why he never did defend his PhD.”

Instead, Hickerson left Indiana University with a master’s degree, in which he focused on an annotated bibliography of North American indigenous songs.

In 1963, he got a job as a reference assistant with the Archive of American Folk Song at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. “The job was too good to turn down.”

“As a reference librarian, people would call or come and visit and ask questions about what we had in the archive, and he would answer them,” Winick said.

He eventually became the head archivist of the American Folklife Center. “He became a nationally known figure in the folk world as our expert on traditional folk songs,” Winick said. “He could give authoritative answers about traditional folk songs, where they came from, who was best known for singing individual songs, and how they changed over time, all of those kinds of questions that people have.”

He had a side gig writing rock concert reviews for the Washington Star, covering bands like The Who and the Dave Clark Five. He wrote a column for Sing Out! Magazine. “People would write in for help with questions about folk songs, and he would answer them there,” Winick said.

He recorded two albums: “Folk Songs and Ballads Sung by Joe Hickerson with a Gathering of Friends” in 1970 and “Drive Dull Care Away” in 1976.

Hickerson worked at the Library of Congress for over 25 years. Although he retired in 1998, he continued to lecture and perform near his home in southern Maryland. “There’s a folk scene in this little town in Maryland where we lived. We were constantly visited by a huge variety of interesting people involved in folk music. Pete Seeger knew me by name,” Michael Hickerson said.

“His concerts were hybrid lectures. At any given concert, there would likely be as much time taken for a song’s preamble/prologue as for the song itself,” Michael Hickerson said.

Hickerson’s passion for archiving bled into other areas of his life. “He printed out every single email he received and organized them chronologically and alphabetically. He would go out to eat in D.C.’s east and southeast Asian restaurants and took every menu home to add to his menu archive.”

In 2013, Hickerson moved to Portland to be near his partner, Ruth Bolliger. He attended folk music events in Portland and he wrote a column for the Portland Folklore Society Newsletter.

“He had a memory like a steel trap,” Michael Hickerson said. “People say’s he a legend; that’s one of the things he’s legendary for—his memory.”

Hickerson had a robust sense of humor. “He was a jokester, a prankster,” Michael Hickerson said. “He had a knack for turning absolutely anything into a pun.”

Hickerson is survived by his partner, Ruth Bolliger, his son, Michael Hickerson, and a grandson.