By Elisa Carollo

Copyright observer

Kim Tschang-yeul always approached art as a tool for lifelong existential and philosophical inquiry—one that sought to heal both individual and collective traumas and distill a new form of expression capable of capturing the universal flux of all things. As his 60-year practice unfolds period by period in the artist’s career survey currently at MMCA Seoul, a kind of personal phenology takes shape, with the suffering and scars of his beginnings gradually transforming into transparent, pure, yet inherently fragile and unstable drops—crystallized illusions of eternalized perfection.

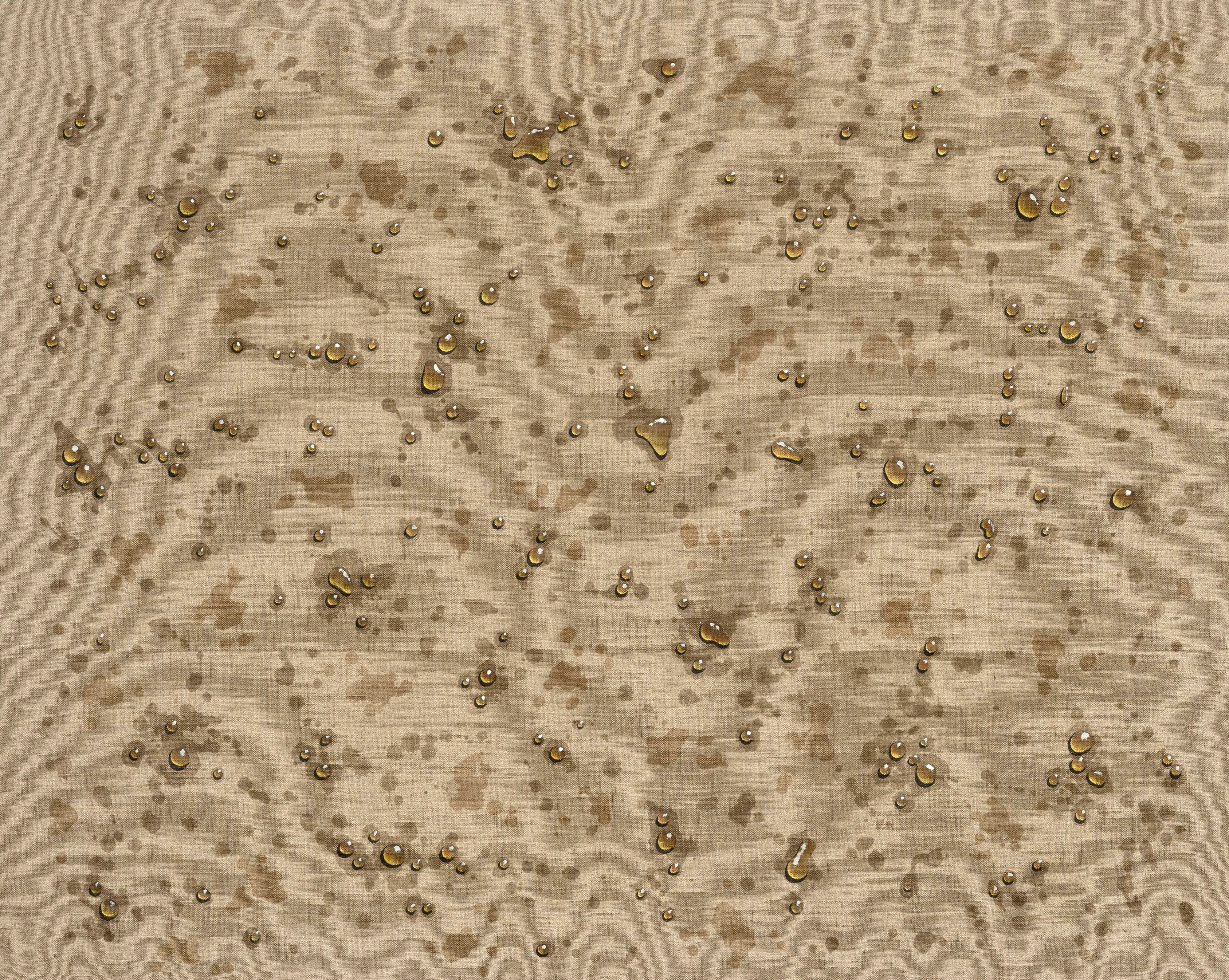

For Kim, the water droplet—a recurring motif that became his signature—always transcended any mere material or idealized depiction. It became instead a potent allegorical vessel for emotional and spiritual exploration, resonating deeply with East Asian philosophical traditions and the historical currents of South Korea itself.

Kim’s journey began in Maengsan, in what is now North Korea, which he left at sixteen as the peninsula fractured under the violence of liberation, division and war. This uprooting, and the conflict that followed, instilled in him an early awareness of rupture, survival and the precarity of existence. The turbulence of the Korean War, his interrupted studies at Seoul National University, and his military service on Jeju Island became the raw emotional and human substrate from which his art emerged—work forged in the tension between memory and erasure, flesh and spirit, transiency and transcendence, and always marked by a deep awareness of the fragility of every human moment and sensation.

By the end of the 1950s, Kim had developed his own version of what might have been described as Art Informel in Europe, pushing painting beyond sterile abstraction into a space where painterly matter could embody and process the traces and wounds of war and human suffering. His early works are haunted, wounded fields—surfaces scarred like battlefields.

From these tormented surfaces, it becomes clear that painting for Kim was never about representation but about exorcism and catharsis: a confrontation with grief and a ritual of both mourning and purification, which could only proceed through the suffering of remembrance, elaboration and eventual acceptance. His writings from this period reveal a painful awareness of the weight of existence:

“Everyone seems so wise, but why do our bodies itch with unease? Even as we scrape away the flesh in pursuit of light and shadow, we return empty-handed. If there is any harvest, it is madness,” he wrote. “We console ourselves by calling this condition—a state neither new nor strange—a harvest, since it springs from the most basic instinct to judge and assign what we call new value.”

On view are the works exhibited at the São Paulo Biennial (1965), a turning point in his career that followed his earlier participation in the Paris Biennale (1961), as he helped pioneer the internationalization of Korean contemporary art. Within the dense and abyssal meanders of his early textures, Kim found a means to console the trauma left by death and loss and to rediscover the power of artistic creation to envision new worlds and futures.

Then came Paris and the new postwar energies of the ‘60s. Somehow, those deep scars turned into mucosal portals. In the exhibition’s second section, “Phenomenon,” Kim’s canvases become porous, psychedelic, psychological spaces that already seem to search for a realm beyond the physical fragility and suffering of the moment, tapping into alternative dimensions of eternity and the infinite creative potential of the mind.

While the exhibition does not explicitly draw this connection, these works align with the visionary spirit of the decade, when a burgeoning psychedelic culture offered younger generations a way to imagine a new world after the wars—a catalyst for new ways of seeing reality. Imagination, for Kim, had already become the path to overcoming trauma. It was during this period that Kim began to explore the notion of transparency as a means to challenge the boundary between vision and imagination. The cell-like constructions once tethered to fleshy reality gave way to a more fluid molecular state, eventually crystallizing—at least momentarily—into the water droplets that would become his defining signature, beginning with Event of Night (1972), long considered his first water droplet work.

Also on view in this section are eight previously unexhibited paintings from Kim’s New York period presented for the first time in Korea. He lived in the city for several years, encouraged by artist Kim Whanki and with support from the Rockefeller Foundation.

Oftentimes, Kim’s water droplets appear in clusters, as if about to merge, evoking processes of cellular coagulation. Yet they remain liminal, singular forms—suspended in precarious relation to one another and their surroundings—implying the potential for movement and transformation at any moment, sometimes erupting into shadowy water stains.

While the simplicity of Kim’s work could be mistaken for decoration, the MMCA survey makes it clear that behind these seemingly serene compositions lies a profound existential and philosophical meditation. What we see is not a stylistic flourish but a symbolic and archetypal representation of the universal nature of all things.

It took Kim a lifetime to complete this process of cleansing, purification and elaboration of trauma—transforming scars into water droplets. “I paint the Waterdrops for a long time as a mental illness of obsession. Annihilation of all my dreams, and pains, and anxieties. Hoping somehow watchable,” appears on the wall of the final room.

Even in their continuity, there is perpetual shifting—a mutability of being, where what we are is constantly redefined through what we feel. His Recurrence series became for him a way to elaborate memory, taking the weight of words and history and turning them into droplets destined to vanish, accepting that human existence, no matter how dramatic, is just a drop in the ocean of a universal continuum.

By 1989, Kim had begun incorporating text and traditional characters into his works. These compositions, dense with layered meanings and semantic interference, exist in a state of tension between the apparent stability and permanence of austere characters and the flux of liquid drops. This series deepens his exploration of the dialectic between permanence and transience: text as the architecture of civilization, the codex of history, the custodian of memory that outlives the individual. Water, conversely, is amnesiac, eternal, cyclical.

In these works, the artist pits permanence against dissolution, inviting viewers to reflect on the fragility of human systems of meaning. History, language and memory all eventually evaporate. Only the natural order remains, in its perpetual cycles of matter, forces and memories. Featured in the gallery is Recurrence SNM93001 (1991), an impressive 7.8-meter-wide painting from the MMCA collection shown for the first time, radiating a luminous, almost auratic presence. Accompanying it is a sculpture that embodies and manifests this tension between the weight of physical existence and the fragile purity of universal forces already encapsulated in the suspended space of a water drop.

The final section of the show, “Recurrence,” probes the source of Kim’s artistic creation through the interplay of language and image in his Thousand Character Classic painting. “Between two pages, Waterdrops is a comma—poetry sipping eternity,” wrote Alain Bosquet in Twenty Drops of Water, a poem for Kim Tschang-yeul. One of the last paintings in the exhibition shows the drop already transformed, now more like a flame, submerged in a smoky, red-tinged atmosphere. The perfection of eternity, once liquefied in a single drop, has already evaporated, returning to the cycle. For Kim, the process of catharsis seems complete. There’s a palpable acceptance of reality as an inescapable circle of birth, transformation, destruction, healing and rebirth—something his practice not only embraced but also translated into a powerfully human-readable, universal, symbolic and poetic form.

“Kim Tschang-yeul” is at Korea’s National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul through December 21, 2025.

More exhibition reviews

This Traveling Exhibition in the U.K. Recasts Gladiators as More Than Sacrificial Lambs

In Elizabeth Glaessner’s “Running Water,” Bodies Become Myths in Flux

‘Why Look at Animals?’ at the National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens

Where Ink Breathes With the Universe: Hung Hsien’s Cosmic Abstractions at Asia Society Texas

Yuan Fang’s Visceral Paintings at Skarstedt Confront the Body’s Fragility and Its Strength