The historical reality that so many generations of Black people not only survived two of the nation’s greatest sins — slavery and Jim Crow — but have also gone on to thrive in spite of them is a distinctly American story of a community’s collective resilience.

The progress of so many African Americans despite an omnipresent backdrop of systemic resistance should be considered a point of pride — not something we should cover up and pretend never happened.

But President Donald Trump doesn’t see it that way. He wants references to slavery removed from many exhibits in the Smithsonian Institution and at multiple parks run by the National Park Service. The Washington Post reported on Monday that among the documentation being targeted is a famous photo of a formerly enslaved man named Peter, circa 1863.

In the image, Peter poses with his bare back exposed, displaying the horrific scars from a whipping he received at the hands of an overseer at a cotton plantation in Louisiana. “The Scourged Back,” as it was called, was used by abolitionists to help people visualize the horrors of slavery and served to galvanize support for the Civil War.

But that’s not the reality Trump wants showcased in America’s museums and parks. He’d much rather thump his chest about the story of America’s greatness and skip over its ugliest chapters. On Aug. 19, the president attempted to justify his position, writing on Truth Social that “The Museums throughout Washington, but all over the Country are, essentially, the last remaining segment of ‘WOKE.’”

He went on to accuse the Smithsonian Institution of being “out of control” and complained that it contains “nothing about success,” which is completely untrue. It makes me wonder how many exhibits in the 21 museums run by the Smithsonian the president has even bothered to visit before coming up with that false assertion.

After my 2016 visit to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., I walked away feeling as if it had taken me on an emotional roller coaster, but my prevailing feeling was pride. I felt proud to be part of the lineage of Africans who had survived the Middle Passage.

I felt proud to be a descendant of my great-grandfather, Robert Armstrong, who was born into slavery in South Carolina in the middle of the 19th century.

I felt proud that our people had been able to overcome Black Codes and poll taxes and just about every other roadblock placed in our way.

As I wrote back then, “the words of Maya Angelou reverberated through my soul: ‘Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave … I am the dream and the hope of the slave.’”

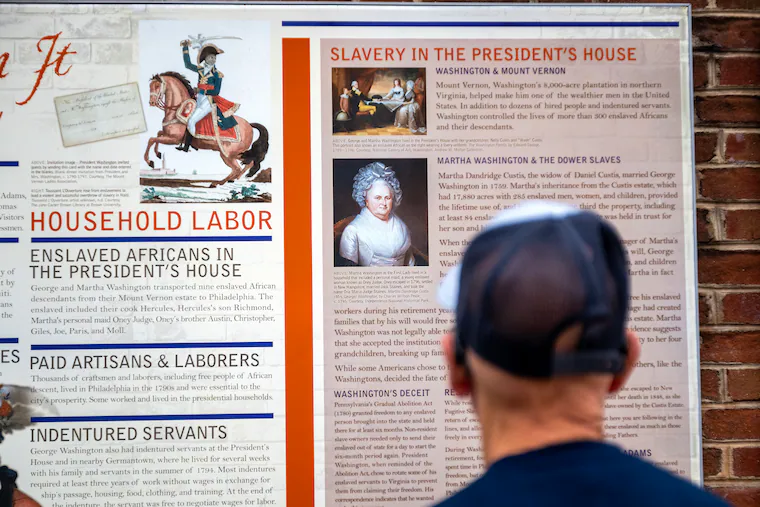

It’s galling that one man can have so much sway over exhibits around the country, including at Philadelphia’s own President’s House, which tells the story of the nine people George Washington enslaved as part of a more complete story about the daily life of the nation’s first president.

I’m grateful that Visit Philly — the city’s main tourism agency — has promised to find a new home for local displays that are removed. We need more nonprofits and organizations to step into the gap that will be left after Trump runs roughshod over exhibits at the Smithsonian and national parks.

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park in West Virginia is also reportedly in Trump’s crosshairs. Last year, my husband and I toured the site of John Brown’s anti-slavery raid in 1859. Exploring the historic reconstruction felt like a giant step back through time. I was amazed to be able to stick my head inside the actual fort where the abolitionist barricaded himself before the infamous raid on a federal arsenal that helped catapult the country into the Civil War.

We visited what was left of Storer College, a school created to teach the formerly enslaved that existed until 1955, and also learned that Harpers Ferry had been the site of the first gathering of the Niagara Movement, a forerunner of the NAACP. It was a lot to take in.

As we drove away, I marveled at the remarkable job the National Park Service had done, not once dreaming I might never again get a chance to experience it as it was.

Trump talks about looking forward, but at the same time, he’s turning back the clock, restoring the names of Confederate generals to Army bases and reinstalling statues of other treasonous losers.

But I have faith this, too, shall pass, and that Trump’s ability to dictate how Black America’s story is told will crumble under the weight of our nation’s historical reality — which is something that ultimately cannot be denied.