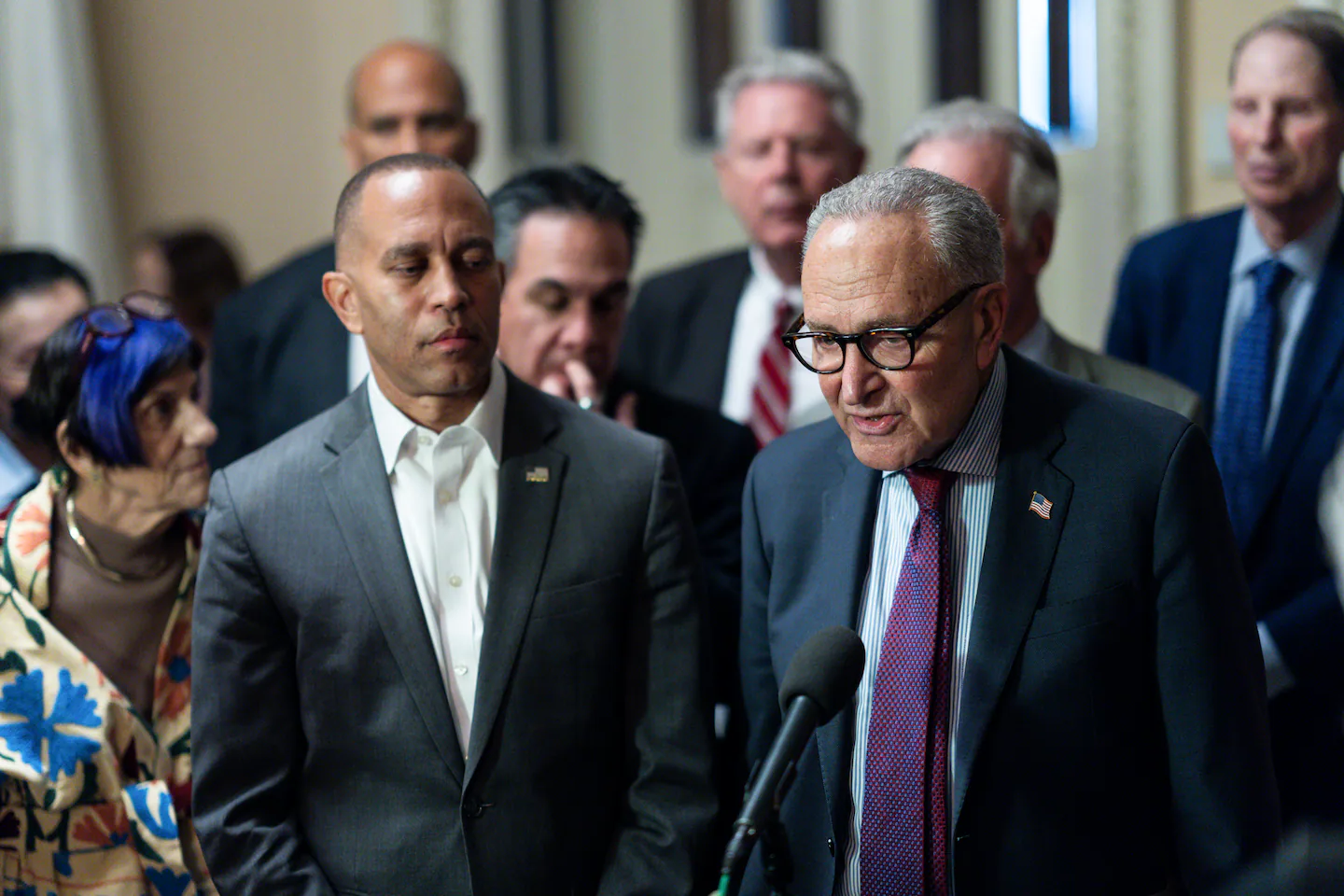

The political dynamic is predictable. Democrats do not control the House, but in the Senate, Republicans need at least 60 votes to pass any spending bill. Given that there are only 53 Senate Republicans, they need Democratic support. Democrats have little incentive to provide it without concessions. As Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer put it, “If one side refuses to negotiate, they are the ones causing the shutdown.”

House Democratic Leader Hakeem Jeffries echoed the point, saying, “House Democrats will not support a partisan Republican spending bill that continues to gut the healthcare of the American people. That’s what this shutdown fight is all about, Mr. President”.

The subsidies were created during the pandemic to make coverage cheaper for low- and middle-income Americans, expanding eligibility and lowering monthly premiums. Millions of families have benefited, in some cases paying little or nothing for insurance. But unless Congress acts, those subsidies are set to expire at the end of 2025.

Because open enrollment begins this fall, insurers and consumers need clarity now. If the subsidies disappear, premiums could spike by hundreds of dollars a month. Democrats see extending them as essential. Republicans see the move as costly and unrelated to the immediate task of keeping the government open.

Republicans, by contrast, are emphasizing restraint. Senate GOP Leader John Thune warned that Democrats “have a choice to make” as the deadline approaches: “They can work with Republicans, or they can shut down the government with all that will mean for the American people.”

House Speaker Mike Johnson has been more blunt. “That’s a December policy issue, not a September funding issue,” he said when asked whether the ACA subsidies would be included in the continuing resolution.

Since its passage in 2010, the ACA has been the most frequent fault line in shutdown brinkmanship. In 2013, Republicans shut the government down over demands to defund or delay Obamacare. (Yes, a Supreme Court ruling it Constitutional saved the law, as did a failed effort in the first Trump administration to scrap it.) In later years, smaller skirmishes over cost-sharing subsidies and repeal votes threatened to derail funding. If you had to pick one policy most likely to derail government funding in the modern era, Obamacare would be it.

The debate today is not the same as it was a decade ago. Then, the law was still new and polarizing. Today, polling suggests it is popular, and millions depend on it. Most Republicans are no longer actively trying to repeal it. Yet the mechanics of legislating mean the ACA still provides fertile ground for conflict. Democrats see defending and expanding it as core to their political identity. Republicans, wary of costs and opposed to attaching policy changes to budget bills, resist those expansions. The result is familiar: the ACA becomes the bargaining chip where broader fights about fiscal responsibility, party branding, and electoral positioning play out.

If the subsidies lapse, the effects will be felt in household budgets as much as in political talking points. Families already pressed by inflation could see health insurance rates rise, even those not buying insurance in the marketplace. Then again, the extra subsidies that will sunset at the end of the year were passed during COVID, and the government long ago announced the pandemic is over.

Shutdown politics is theater as much as governance, but here are two separate items that have actual consequences. Democrats want something, Republicans will have to give something to clear the filibuster, and health care remains the obvious fault line. Whether the government shuts down or not, the fight over Obamacare’s subsidies is one more reminder that in the budget battles of the 21st century, health care is never far from the spotlight.

James Pindell is a Globe political reporter who reports and analyzes American politics, especially in New England.