By Ben Lewis

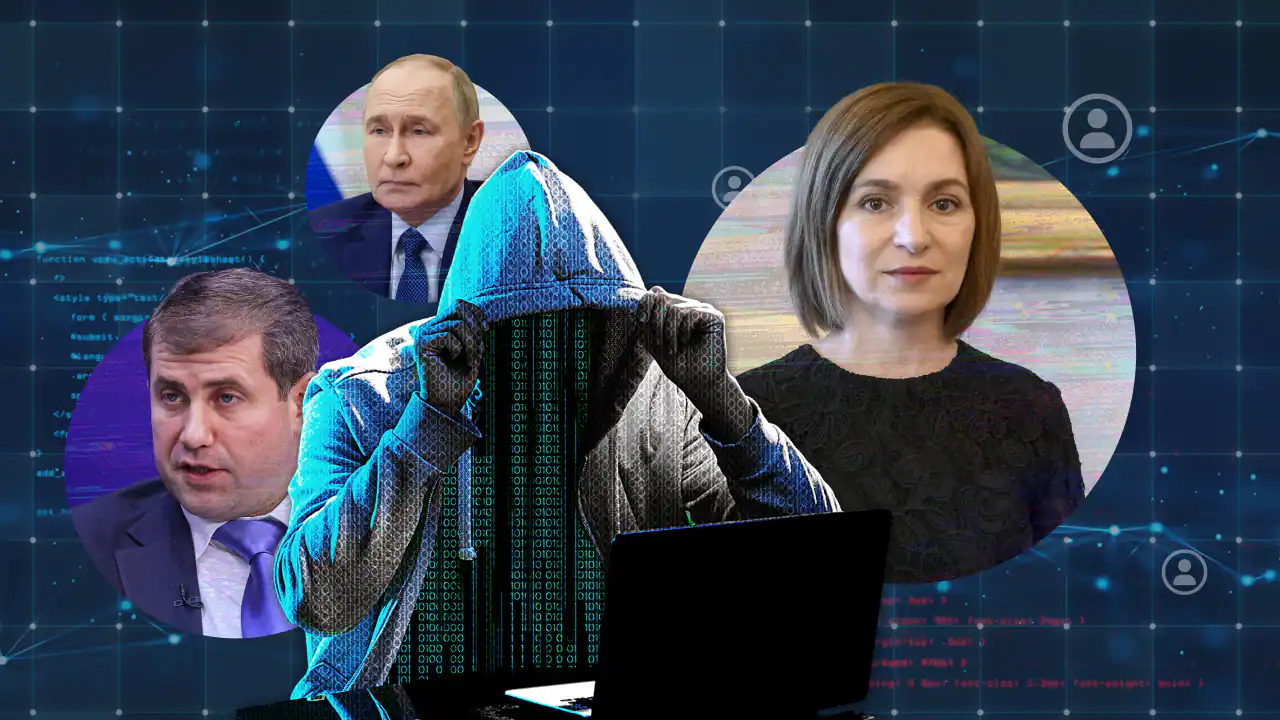

Copyright sbs

It has Romania and the European Union (EU) to the west, Russia to the east and the war in Ukraine on its border. Like many former Soviet states, it has gravitated towards Europe in recent years. President Maia Sandu , re-elected last year, is a firm supporter of plans to join the European Union. “The cruel war waged by Russia against Ukraine shows us daily, Europe means liberty and peace,” she declared recently. “Putin's Russia means war and death.” But her Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) could lose its majority in upcoming parliamentary elections, with polls suggesting the Russia-friendly Patriotic Bloc is on the rise. That's, in part, thanks to a disinformation and propaganda campaign backed by the Kremlin . In an unremarkable apartment building just outside the centre of the Moldovan capital Chișinău, staff at Watchdog, an NGO which tracks voter fraud and misinformation, are analysing their latest find. It's a widely shared TikTok video of a young man discussing the EU. But the man is not real — he's AI-generated. And what he's saying is untrue. Watchdog has uncovered a vast network of social media profiles, some run by real people under false identities, others a mix of automated and human activity. They spread lies about Moldova's government, European diplomats and the war in Ukraine. Anything that benefits Russia. Investigators have identified 900 accounts in this network, but they believe the true figure is potentially in the tens of thousands. “Anything you can imagine and multiply it 10 times, it's something which has never happened in any other place,” Watchdog's executive director Valeriu Paşa said. “The intensity, the quantity, the spread, the formats, channels, topics, everything from AI-generated content to top political parties repeating and amplifying Russian narratives here.” It's not just about the digital space. Moldovan oligarch and Kremlin-aligned fugitive Ilan Shor recently promised to pay protesters US$3,000 ($A4,500) a month to join anti-government demonstrations. During last year's presidential election and a referendum on EU integration (which narrowly passed), Moldovan authorities reported thousands of cases of voters receiving money from Russian bank accounts. The Kremlin denied any involvement, but investigators think otherwise. “Our estimation is that last year Russia spent here at least 150 million euros ($265 million) for this interference,” Paşa said. “Authorities are talking about 200 million ($354 million). To give you a sense, this is more than 1 per cent of our GDP. That's crazy in any country, but we are small and poor.” Watchdog accuses the pro-Russian Patriotic Bloc of benefiting from Russia's disinformation onslaught. At the headquarters of the Socialist Party, the bloc's biggest member, its star candidate denied the claims. “You ask about finances, we have a central electoral commission. I cannot imagine how Russia could send us money,” Olga Cebotari said. “It's impossible. I want to see the proof.” The Socialists insist they're not anti-West, favouring good relations with both Europe and Moscow. But they refuse to blame Russian President Vladimir Putin for his war next door, citing Moldova's neutrality, which is written into its constitution. It's a view shared widely in Gagauzia, an autonomous region of Moldova, where Russian is the predominant spoken language. Despite the area having received significant EU funds, pro-Russian parties dominate the vote in the region. Larissa is tidying her market stall as she tells me she has no problem with Europe but still has fondness for the Soviet Union. Putin's war in Ukraine is seemingly not an issue. “As far as I know, Russians are good, kind people. They would never start a war. When did Russia start a war? When did they bomb someone? Tell me,” she said. Our interpreter points out that Russia started the war in Ukraine after launching its full-scale invasion in 2022. “Because the Russians within Ukraine were oppressed,” she quickly responds. That's a Kremlin talking point and one heard a lot here. Many believe Russia has a right to its former territory. “Lots of people believe that Russia should own this land,” Gagauzian journalist Mihail Sirkeli said. “The Soviet Union collapsed, but people continued to watch Russian television. We were too dumb to understand that this is a weapon and Russia will weaponise it. We understood it very late, and before we understood it, they already weaponised the people.” Closer to the Romanian border, views are vastly different. Memories of the Soviet Union are not so rosy. It's harvest season and hundreds of people are picking grapes, which have grown in the region for 5,000 years. “We think during these 5,000 years we learned a little bit how to do a good wine,” winemaker Ion Luca joked. “Now our task is to promote it as well because everyone knows about [Australian wines] Yellow Tail or Penfolds, but nobody knows yet about a good Moldovan wine.” Russia and former Soviet states were once the biggest buyers, but that has changed over the past decade and accelerated once the war began. The idea of Moldova turning its back on the West worries Ion, who not only fears losing access to the critical European market but also a return to an era he thought was long over. “Concerned is not the right word,” he said. I'm terrified. I cannot imagine Moldova again getting closer to a criminal state. Russia is a criminal terrorist state. I'm born in USSR. I lived the last 10 years of USSR and I don't want it anymore.” Ion will vote for PAS, hoping Moldova's march towards European integration continues. The government claims pro-Russian parties would seek to slow or even stop the EU application process, as has happened in Georgia. Even worse, they fear Moldova could get dragged into a conflict it has sought to avoid. “They are trying to install a pro-Russian government in Moldova to use our country in their war aims to try to pressure [Ukrainian sea port] Odesa, to use our airport, our infrastructure,” claims Radu Marian, a PAS politician running for re-election. “They're not 'investing' hundreds of millions of dollars in these elections just because [they support] the pro-Russian politicians, they do it to try to take over Moldova and to destabilise the whole European continent.” But some opposition parties, like those in the Alternativa Bloc, accuse the government of using the Russian threat for its own benefit. “They're trying to show this battle as a battle, you know, good and evil, us against everybody else, PAS against all the Kremlin forces,” Gaik Vartanean, a candidate for Alternativa, said. “Basically, whoever is against PAS politically, they are considering a Kremlin force, which is not true.” Yet the leader of his party, Chișinău's mayor Ion Ceban, was recently banned from Europe's Schengen travel zone for what Romanian authorities described as 'national security reasons'. Investigators say the proof of Russian election meddling is undeniable and authorities are struggling to keep up. “At least 40 per cent of votes are the result of all this nasty phenomena,” Watchdog's executive director Paşa said. “If Russian proxies take control of the parliament, Moldova can simply lose its sovereignty.” Moldova will go to the polls on 28 September. download our app subscribe to our newsletter