By Bernard Chan

Copyright scmp

China’s recent high-profile diplomatic activity, including the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Tianjin and the Victory Day parade in Beijing in the same week, conveyed more than international headlines suggested.

Although much of the media spotlight focused on the optics of Russian President Vladimir Putin, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, I think the real story centres on pragmatic engagement, regional reassurance and the realignment of partnerships across Asia.

In a world defined by growing geopolitical tensions, these events also highlight how many countries in China’s vicinity seek to avoid taking sides while remaining engaged with Beijing.

The SCO summit, held over two days, brought together leading officials from over 20 nations across Asia, Europe and Africa. This year’s summit showed China’s ability to unite neighbours near and far for productive discussions on trade, security, technology and diplomatic cooperation.

The scope of the guest list was intriguing. Alongside the key members (China, Russia, India, Iran, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan), countries such as Mongolia, Turkey, Myanmar and other Southeast Asian states participated.

Notably, Modi’s attendance signalled renewed Sino-Indian engagement after years of border tensions. While old disputes persist, both powers have expressed a commitment to increased cooperation and engagement.

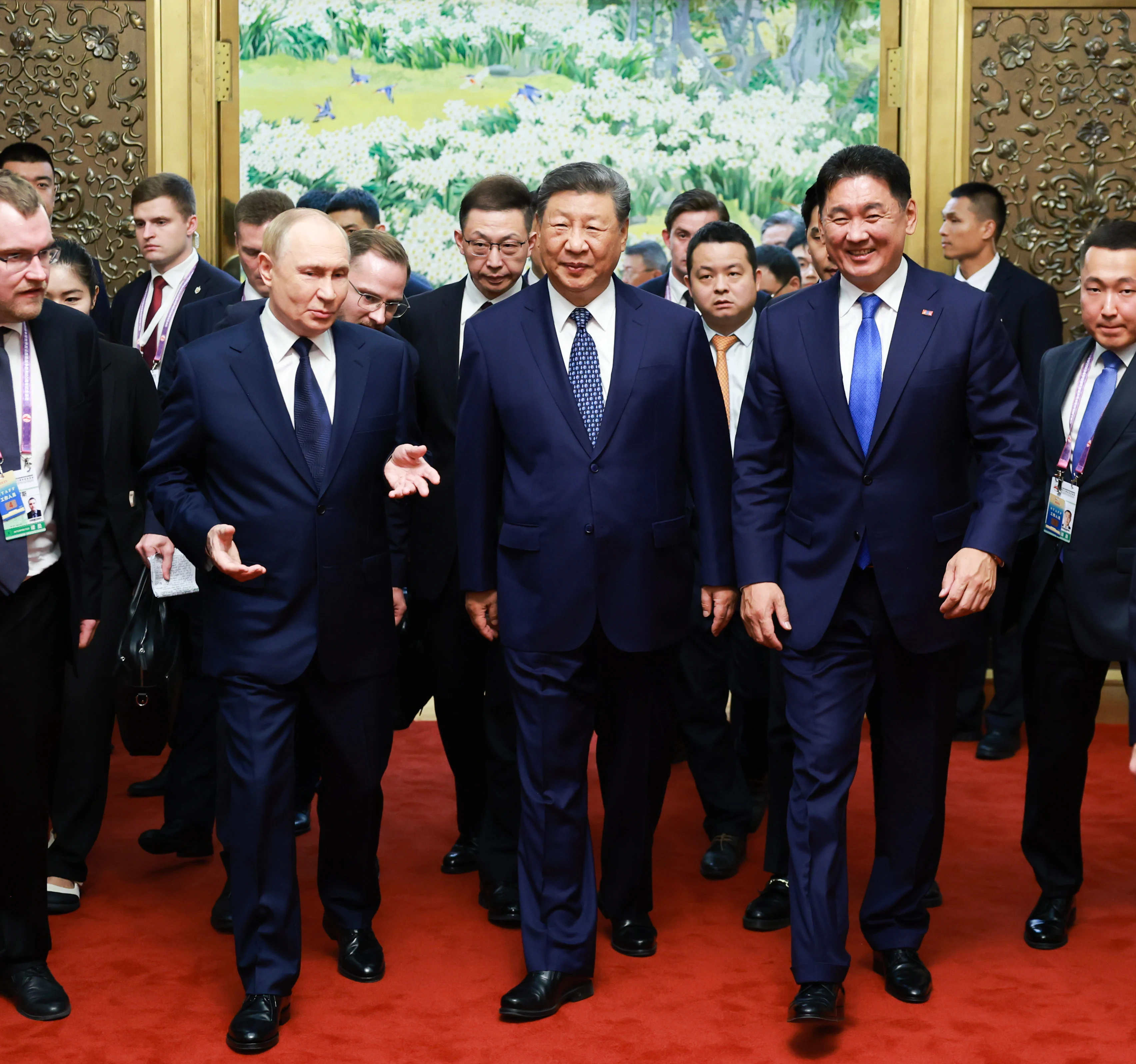

Just days later, Beijing held the Victory Day military parade to commemorate the end of the Second World War, with President Xi Jinping flanked by guests including Putin and Kim – a joint appearance widely seen as a symbolic counterbalance to US influence in the region.

The parade was attended by heads of state and government leaders from 26 countries. South Korea’s National Assembly Speaker Woo Won-shik also attended, reportedly engaging in a brief exchange with Kim that underscored the conciliatory tone of the occasion. Notably absent were Manila and Tokyo, although former political figures from Australia, Belgium, Greece, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Romania, Switzerland and Taiwan took part in the event.

Among these former leaders, Japan’s Yukio Hatoyama attracted particular attention. His presence at the 80th anniversary commemoration held symbolic significance. Despite domestic criticism, the former prime minister attended with a reflective attitude, recognising Japan’s wartime past and emphasising that honest engagement with history is essential for reconciliation and understanding.

Despite all the fanfare, the parade’s central message was deterrence rather than aggression. Xi’s speech balanced praise for China’s sacrifices with reassurances that the country’s military modernisation aims to secure, not to conquer.

China’s narrative seeks to reference its “century of humiliation” and the more than 35 million lives lost as the country waged resistance against fascist aggression that began in 1931. It depicts those sacrifices as part of a broader contribution to global peace and stability, emphasising the need for strength to deter aggressors.

This focus on resilience at home, combined with international outreach, reflects a pragmatic approach that connects national renewal with the development of constructive partnerships. Increasingly, that mix of defending core interests while engaging with others has become the hallmark of China’s foreign policy message.

A recurring theme, often overlooked, is the importance China places on maintaining working relationships with its immediate neighbours, even those with contentious border histories. That nearly all proximate Asian states were represented at the Beijing parade highlights a deliberate effort at regional inclusion despite adversity.

Experienced observers, including Chatham House and the Asia Society Policy Institute, have consistently recognised that the process of normalisation, dialogue and occasional compromise is essential in a region where historical grievances and contemporary disputes frequently threaten stability. For China, engagement with India, Vietnam and the rest of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations is both a sign of confidence and a practical step in managing conflict.

Western commentary might focus narrowly on the optics of strongmen sharing a stage, but for many of China’s neighbours, the more compelling image was one of inclusion. The presence of nearly all bordering states, despite long and complex histories, shows dialogue with Beijing remains not only possible but essential. That willingness to engage, even amid unresolved disputes, signals maturity and confidence.

Rather than view these gatherings simply as a grand spectacle, it is more insightful to interpret them as part of China’s broader diplomatic strategy: determined to protect its security, but also focused on building a network of partnerships that can stabilise the region. For many neighbouring countries, engaging with China offers practical benefits and allows them to navigate geopolitical tensions without clearly taking sides.

For Washington and its allies, the lesson is clear: in the emerging world, influence cannot be maintained by pressure alone. Nations that feel respected and listened to may hedge or balance, but they rarely turn away from a partner willing to engage in dialogue and inclusion. Recent events underscore this point: the real contest is not about pageantry, but about which power can create space for others to feel secure, dignified and heard.