By Alex Knapp,Forbes Staff,Oriana Fenwick

Copyright forbes

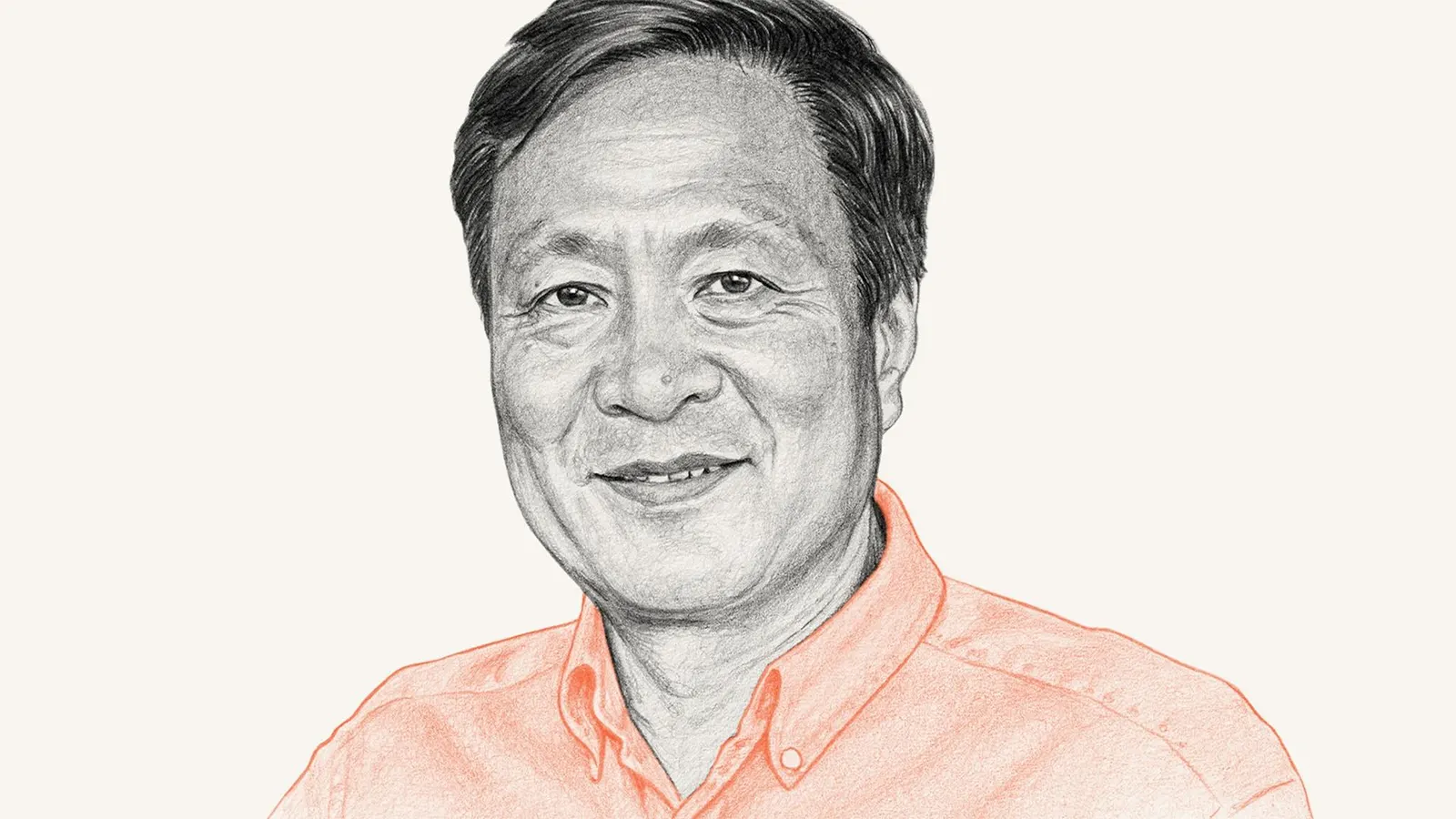

Kongjian Yu’s company is designing green spaces to absorb rainfall and mitigate natural disasters.

In July 2012, a massive flash flood struck Beijing as rainfall in the Chinese capital caused the nearby Juma River to overflow its banks. In less than 24 hours, nearly 60,000 people were forced to evacuate their homes and 79 people died. Damages to the city were estimated at around $1.6 billion.

That flood and others like it the same year spurred the Chinese government to pursue new flood control strategies, among them the so-called “sponge city” which uses greenspaces to absorb and retain rainwater. It’s a dramatically different approach than building large-scale water diversion infrastructure like levees and concrete, and was pioneered by Kongjian Yu, 62, the founder of landscape architecture firm Turenscape.

Conventional flood strategies, Yu said, “accumulate water, speed up water and fight against water.” By contrast, he designs landscapes that “capture water, slow down water and embrace water.” These same green spaces also help to cool down cities, which see higher temperatures than their surrounding regions because of the prevalence of asphalt and concrete, and to recycle rainwater for local uses.

In 2015, China made sponge cities a national policy–in large part at the urging of Yu, who made hundreds of presentations to Chinese officials over the years. His firm had already proved the concept in cities like Jinhua, where his firm replaced a flood wall with its own landscaping, resulting in improved stormwater control. It launched a series of small-scale pilot projects in dozens of cities, and set standards for local regions to adopt. The goal is for 80% of cities to recycle 70% of their rainwater by 2030. According to the Chinese government, around 40,000 sponge city projects were completed by 2020, and that year saw an amount of rainwater recycled equivalent to about 20% of its total urban water supply. More than 70 cities in China have now begun sponge city initiatives, though issues with implementation and funding have hindered some and in most cities they have not scaled to the point where they can yet prevent extreme flooding events.

Yu, who’s being honored this year as a Forbes Sustainability Leader, has played a major role in China’s plans. His company, Turenscape, has designed over 1,000 sponge city projects, including parks, development districts and other infrastructure across more than 250 cities since he founded it in 1998. It’s a lucrative business bringing in around $30 million a year for the design and consulting services it provides, he said.

The climate crisis has intensified rainfall in many regions, making the need for flood control more urgent. In the past 25 years alone there’s been a 134% increase in catastrophic floods. According to a report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, what used to be once a century coastal flooding events could become annual by 2100. Since 2000, global economic damages from flooding have exceeded $730 billion.

The inspiration for sponge cities came from a trip home to China in 1996 while Yu was studying design at Harvard. China’s government was pushing urbanization, but Yu was appalled by what he saw–particularly huge concrete infrastructure aping Western designs, which were intended for a different climate than China’s monsoon seasons. “It was totally wrong and the opposite of what I had learned at Harvard about modern science and ecology,” he said. It also ran counter to his own memories of growing up in a small village, where ponds and wetlands captured water that was then used during the dry season. He decided to return to China permanently in 1997, where he established the College of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at Peking University.

Yu founded Turenscape the following year. The name, he said, comes from “tu”, which means “Earth” and “ren” which means “humanity,” which symbolizes “a new relationship between land and people.”

Capturing water involves building urban elements that can safely retain it — permeable sidewalks, rain gardens and retention ponds. These features prevent runoff–which can carry pollutants–while recharging local groundwater supplies which in many places is being used up faster than it’s being replenished. A recent study from a team of international researchers found that this decline is accelerating in about 30% of the world’s aquifers.

The company’s designs are also intended to reduce the fast water flows in flash floods; they often use long serpentine creeks, vast new wetlands and terraced landscapes to slow and contain surges of stormwater The designs naturally accommodate fluctuations from tides and seasonal changes, reducing peak flooding and improving local water quality by limiting topsoil erosion and filtering pollutants.

Yu first put his sponge city principles into practice in the city of Zhongshan, turning an old shipyard into a park. Completed in 2002, Turenscape’s design reintroduced native biodiversity in the forms of plants and trees, and even incorporated some of the skeletons of the old infrastructure, such as rails and cranes, as a way of preserving the area’s history. When local regulations required a waterway to be widened, which would have forced the destruction of large numbers of trees. Turenscape instead dug a channel around the trees, preserving the local ecosystem while still enabling stormwater to flow.

Turenscape has grown alongside its success. It now boasts more than 300 employees and Yu said the company is expanding into other countries in Southeast Asia as well as India. Recently, it helped design the Benjakitti Forest Park in Bangkok, Thailand, turning an old tobacco factory littered with single-story warehouses into a 104.5 acre park in about 18 months. Incorporated into the design are three different constructed wetlands with hundreds of small islands that both promote local biodiversity and “can handle half a million cubic meters of stormwater,” Yu said, enough to fill 200 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Other countries have started to put their own spin on the sponge city concept. Copenhagen, Denmark, for example, is halfway through a project slated to be completed in 2032 that incorporates many of Yu’s principles, with hundreds of nature-based, flood-mitigation systems that are already working.

Yu is excited to see the concept catch on. “I want this to become a model that can be amplified and applied by anyone,” he said. To that end, he plans to start an AI company within the next two years, which will train software on Turenscape’s large project datasets. Its models could then be used by urban planners to help design their own sponge city projects that’s attuned to local conditions and resources. “That’s my vision, which I’m going to establish soon,” he said.

More from Forbes

Got a tip? Share confidential information with Forbes.

Editorial StandardsReprints & Permissions