By Elena Giordano,Seb Starcevic

Copyright politico

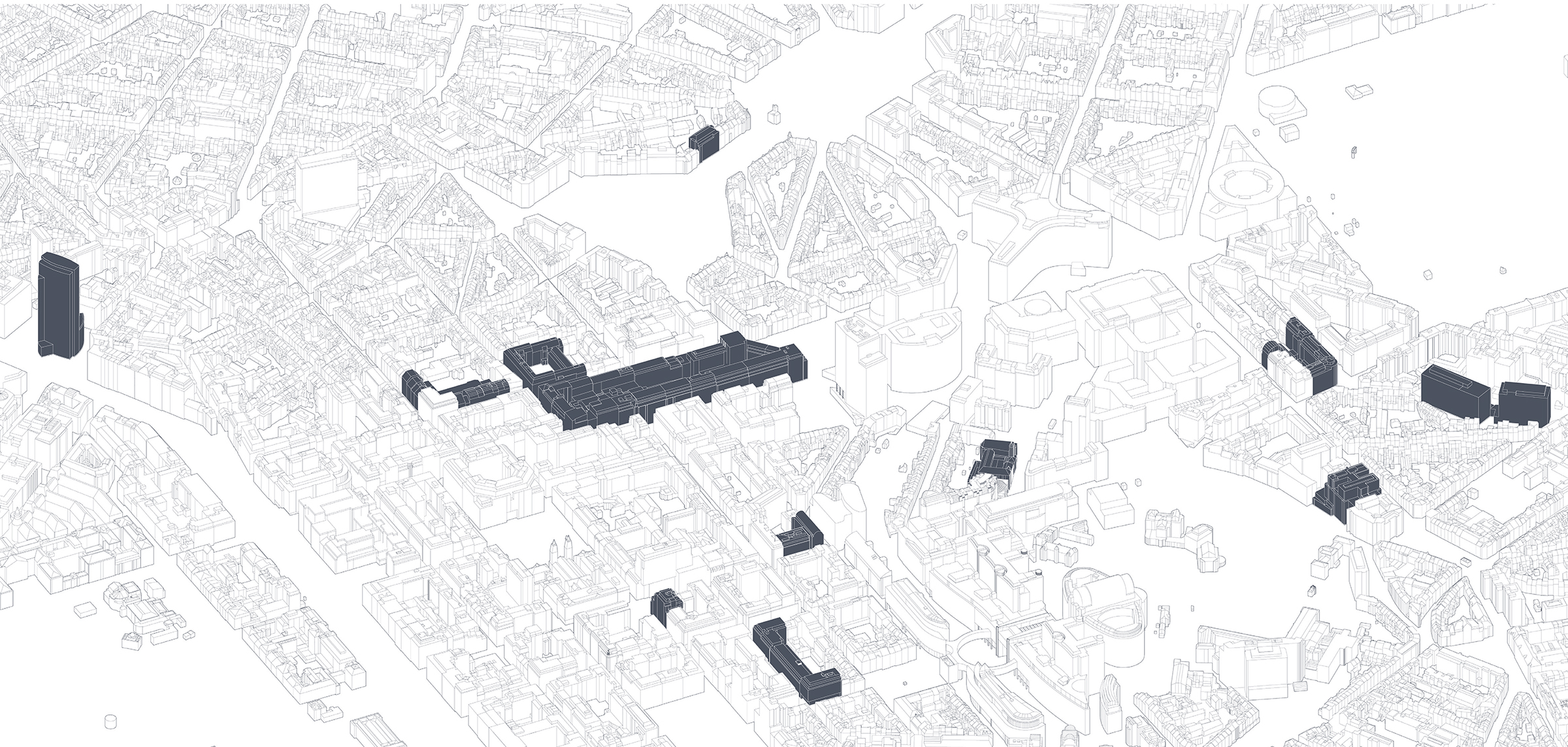

At the center of it all is the Schuman roundabout, a traffic-choked junction now under full-scale redevelopment. By mid-2026, the concrete-heavy site is set to become a greened-up pedestrian promenade.

Just down the road, a sprawling new European Commission conference center is rising at Rue de la Loi 93-97, replacing a long-abandoned office block and once-beloved mural. Another structure at Rue de l’Industrie 44 has been razed, although its future remains unclear. Around a dozen more sites around the quarter, from Rue de la Science to Avenue de Cortenbergh, are now in some state between demolition and reconstruction.

Several streets, such as Rue Guimard, will be ripped up and have trees planted as part of an ambitious master plan to make the quarter greener. To that end, the Commission last year sold 23 of its office buildings to Belgium for €900 million to redevelop, in a bid to build a “modern, attractive and greener” district.

It’s a grand vision that taps into Brussels’ long history of chaotic redevelopment — captured in the deprecating term “Brusselization,” coined during the city’s notorious construction boom of the 1960s and 1970s. That era saw unchecked freedom to developers, razing much of the city’s Art Nouveau history and transforming the EU capital into a mishmash of architectural styles.

But despite the buzz around the ambitious current makeover, not everyone is sold. With local businesses worried about the long-term impact on foot traffic, a paralyzed Brussels government, allegations of budgetary fraud and a city deep in debt, this redevelopment risks becoming the ultimate stress test for the capital of Belgium — and the EU.

Locals feel the strain

Among business owners and employees around the Schuman roundabout POLITICO talked to, not everyone was convinced that the upheaval will be worth it.