Self-government and getting rid of the Indian Act has become an even more timely discussion, says author

By Deb Steel,Shari Narine

Copyright windspeaker

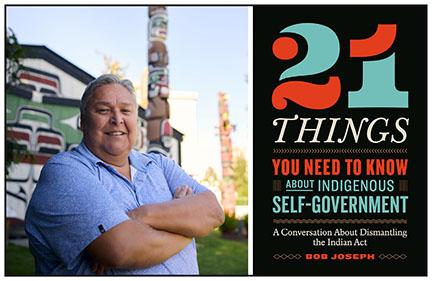

It’s a “perfect storm,” says Bob Joseph about the timing of the release of his recent book.

21 Things You Need to Know About Indigenous Self-Government: A Conversation About Dismantling the Indian Act coincides with the push by the new federal government to implement its first major piece of legislation, the One Canadian Economy Act, since being elected.

Joseph, a member of the Gwawaenuk Nation in B.C., and an initiated member of the Hamatsa Society, a deeply spiritual ceremonial group of the Kwakwaka’wakw, lists the first “thing” about self-government as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which sets the standard for their treatment. That standard includes the 16th point in his book: the right to free, prior and informed consent for any projects to be developed on traditional territories.

While new Liberal leader and Prime Minister Mark Carney repeatedly claims that Indigenous peoples will be consulted as Canada “build(s) big, build(s) fast” in response to United States President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs that are impacting the Canadian economy, Joseph isn’t convinced.

“The tariff work stuff is being done in the national interest, which gives the government sweeping powers to just do this stuff… I doubt there will be a lot of negotiation or consultation. I’m hopeful that there will be, but I doubt it,” he said.

As Carney communicates that the country is “in crisis,” Joseph is hopeful that non-Indigenous Canadians, who may get upset that First Nations are not embracing development on their traditional lands at breakneck speed, will draw an understanding through what is presented in 21 Things.

“As it’s shaping up now, (with) the duty to consult, we’re hearing a lot of communication from the First Nations leaders across the country who are saying, ‘We need to be consulted and we haven’t and we’re really concerned that you’re just going to run roughshod on our Section 35 rights’,’” said Joseph.

Section 35 rights, as he explains in 21 Things, “recognizes and affirms existing Indigenous and treaty rights.” He calls this a “watershed moment (that) marked the end of forced cultural assimilation” through the Indian Act.

Assembly of First Nations National Chief Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak has been clear that Canada has failed to consult with First Nations on the creation of the One Canadian Economy Act, which comprises the Building Canada Act and the Free Trade and Labour Mobility in Canada Act.

“It’s set the stage for, I think, an interesting fall,” said Joseph.

Nine First Nations in Ontario have already begun legal action against the Act. That’s a direction Joseph is confident the Canadian government anticipated.

“I’m sure internally the Crown (is saying), ‘What’s the downside of not talking to them? They’ll come after us with judicial reviews and try to slow us down. But the national interest gives us sweeping powers so we can continue to move ahead. We’ll probably deal with the fallout later on where the courts will wag their finger at us for not spending more time and we’ll have to do compensation or other kinds of things.’ I think it’s all been talked about,” said Joseph.

He goes on to write that Section 35 recognizes inherent rights and “self-government is an inherent right for Indigenous Peoples in Canada.”

Of Carney’s promise to move forward in partnership with Indigenous peoples, Joseph said, “We haven’t really seen that yet.”

In 21 Things, Joseph writes about business partnerships that generate jobs and other benefits for First Nation citizens, as well as resource management partnerships between development companies and Indigenous communities.

He emphasizes that “partnership” is not what the Indian Act creates. Instead, the Indian Act dictates a trustee-wardship relationship, as he notes in point four of his book, with the federal government holding the balance of power over First Nations.

“This…(is) why we want to see Indigenous nations return to self-government,” Joseph writes.

And looking at what Carney is calling an “austerity budget,” Joseph is expecting billions of dollars to be cut from Indigenous Services Canada over the coming years, which in turn means less monetary support to First Nations.

While the Indian Act is “not a relationship that’s there to help,” said Joseph, he stresses in 21 Things that self-government doesn’t mean that the federal government drops its fiduciary duty to Indigenous nations.

“It’s time to really consider how Canada invests in its relationship with Indigenous Peoples…Economic certainty in Canada means no need for Indigenous protests, blockades, negative media campaigns, and legal challenges when it comes to industrial or infrastructure development because Indigenous Peoples are participating in decision-making and outcomes,” he writes in his 19th point, which states “supporting self-government is an economic and moral opportunity.”

Dismantling the Indian Act and leaning into self-government, which will take different paths for the 600-plus First Nations, is the only way First Nations can become self-reliant, self-determining and self-governing, Joseph argues.

21 Things is a conversation Joseph hopes will spur “curious” questions from non-Indigenous Canadians that will lead to an understanding of the obstacles that First Nations face under the Indian Act and why self-government is an important step.

As for the One Canadian Economy Act, Joseph hopes “curious” questions include who should be consulted as the federal government greenlights projects.

“So, for the duty to consult, are we talking to the right people because we’re going to be moving so fast (that) the obvious place that they’re going to look is back to the band chief and council, so we’re back to where we were 10 years ago at the start of the big infrastructure debate. How are they going to include the traditional leaders, if there are any, and what about the people?” said Joseph.

As he writes in 21 Things, First Nations had traditional governing structures but the Indian Act implemented an elected chief and council structure meaning that while they “are elected by their people…(they) are accountable to the federal government because the federal government controls their mandate and funding (which pays their salaries).”

“I think the conversations are going to be timely,” said Joseph. “I think for Indigenous people and for Canadians, I hope you’ll feel comfortable joining the conversation. There’s a lot of insights in there that can be helpful. I’m hoping to learn a lot myself from the conversation.”

21 Things concludes with actions non-Indigenous Canadians can take, including advocating for the dismantling of the Indian Act and embracing at least one of 94 Calls to Action as outlined in the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on Indian residential schools.

Next year marks 150 years since the creation of the Consolidated Indian Act of 1876, which has been amended over that time.

Joseph has also authored 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act, which was released last year. It broke down ways the Indian Act shapes, controls and constrains the lives of Indigenous people. Joseph has other published works, including Indigenous Relations – Insights, Tips & Suggestions to Make Reconciliation a Reality, written with Cynthia F. Joseph.

21 Things You Need to Know About Indigenous Self-Government: A Conversation About Dismantling the Indian Act is published by Page Two Books and is now available through https://21things.ca/you-need-to-know-about-indigenous-self-government.