By Eleanor Barlow

Copyright standard

Southport killer Axel Rudakubana could and should have been stopped before launching his murderous attack on children, a public inquiry heard.

Families of the children he stabbed and killed criticised the role of safeguarding services and questioned the part played by Rudakubana’s own parents, the hearing was told.

Warning signs were missed and the killer’s history of disturbing behaviour and violent behaviour not addressed, the inquiry at Liverpool Town Hall heard.

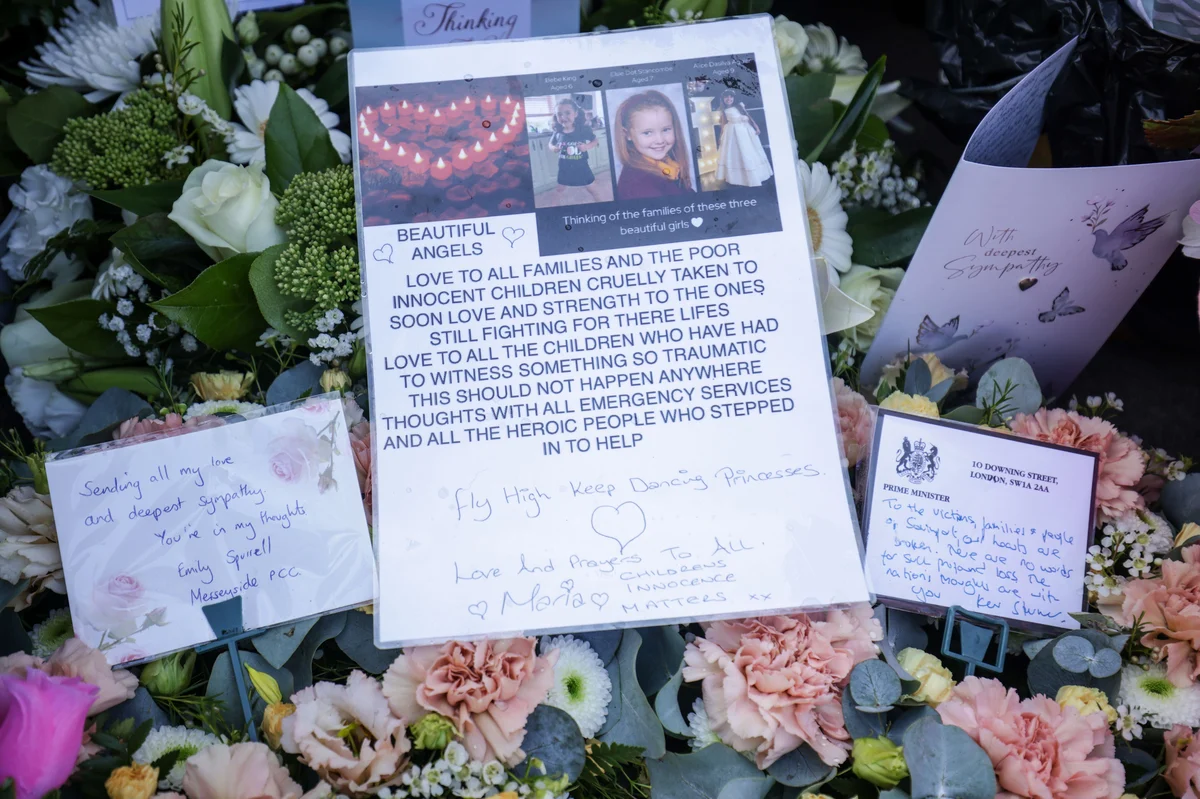

Rudakubana, 18, killed Alice da Silva Aguiar, nine, Bebe King, six, and Elsie Dot Stancombe, seven, and attempted to murder 10 others in the attack on a Taylor Swift dance class for young girls on July 29 last year.

Nicholas Bowen KC, representing all the bereaved families, read a statement from the Stancombe family.

It said: “When a parent knows their child is dangerous, allows them to possess weapons and authorities have already visited the home, how is that not neglect?

“If a child were malnourished or unwashed, social services would act immediately. But when a child is surrounded by weapons, involved in violent behaviour and known to be a threat, the system does nothing.

“That is a failure. No action was taken. Why?

“Our daughter paid the price for that failure.

“When does a parent become complicit in a crime committed by their child?”

The parents of Bebe King, likewise in a statement cited a “chain of failures, across systems, across services, across safeguarding.”

It added: “There were warnings missed. Red flags ignored. Risks underestimated.”

Earlier, Mr Bowen, in an opening statement on behalf of the bereaved families, said Rudakubana had walked through “unlocked doors” to murder and maim children using an £8.39 kitchen knife he had bought off Amazon.

He said responsibility fell not only on public bodies failing to protect public safety but also on the killer’s family, who knew but ignored the risk he posed.

Mr Bowen told the hearing but for multiple failures, the families believed Rudakubana “could have and should have been stopped.”

The hearing was told no one state agency, either in police, schools, health or social services had the “full picture”, but none had “joined the dots”.

Mr Bowen cited the incident when Rudakubana, three times referred to anti-terror government intervention programme Prevent, was reported missing by his family and found by police on a bus, carrying a knife – more than two years before the fatal attack.

He said it likely if a full assessment had taken place, then authorities would have discovered the increasing risk he posed, his purchase of knives and weapons online and the aggression he was displaying at the family home he shared with his parents, in Banks, near Southport.

Mr Bowen reminded the inquiry about evidence that Rudakubana had repeatedly taken a knife into his school, saying he wanted to kill another pupil he alleged had bullied him and attacked another child with a hockey stick.

Asked by one teacher why he took a knife to school, the killer replied, emotionlessly and without eye contact: “To use it”, with the teacher remarking “there was something so cold” in his response, the inquiry heard.

But despite the involvement of various child health and safeguarding professionals, Rudakubana “fell below the radar” Mr Bowen added.

David Temkin KC, representing 18 families whose children were present during the attack, said: “These families have anonymity by necessity but they ask this inquiry doesn’t remember the face of evil but rather their brave daughters.”

He said there were many ways the inquiry might consider Rudakubana had fallen “between the cracks” and highlighted missed opportunities related to the killer’s propensity for serious violence, his educational needs and his family environment.

Mr Temkin said there was evidence that during a meeting between Rudakubana’s school, social services and health workers in January 2020 a representative from the child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) offered a £5 bet for anyone who could predict what happened next.

He said the families were “extremely concerned” about an evidential picture which indicated a “series of system failings, complacency, a lack of curiosity and inadequacy”.

The hearing continues.