The digitization of everyday life has inundated us with more economic data than ever. And yet, government statistics on real economic conditions seem to be growing ever less reliable. Doubts began spreading even before President Donald Trump fired the commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. For years now, response rates to surveys that are at the heart of the official statistics have been dropping. Data-gathering agencies release key metrics long after the fact, and they are chronically underfunded.

This situation is unsustainable. Business decisions about hiring, firing, and investment depend on knowledge of what’s happening in the wider economy. So do the choices made by policy makers in the White House and at the Federal Reserve. An incredible range of sophisticated private sources—including real-time payroll data, online transaction records, and consumer-spending databases—offer alternative sources of fine-grained, up-to-the-minute data that could, under the right conditions, be used to supplement a survey-based approach and provide a more dynamic and accurate picture of the state of the economy. The problem is that the government is not even trying to use them.

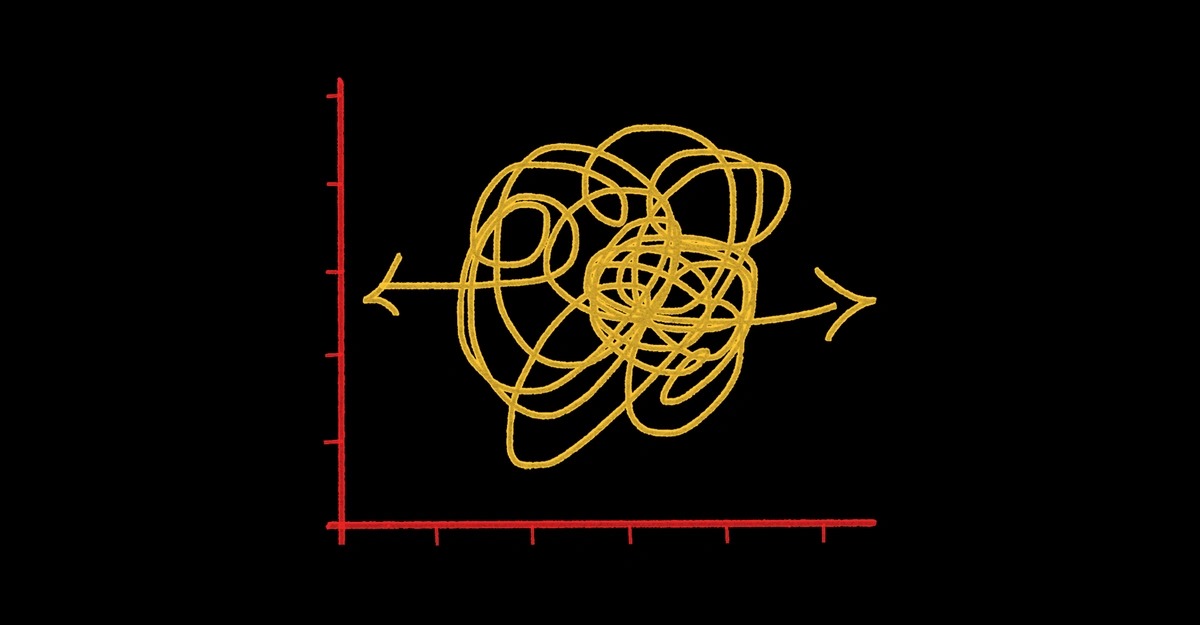

These issues were underscored last week, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics released preliminary revisions to its jobs data from March 2024 to March 2025 suggesting that the economy added about half as many jobs over that period as originally reported, for a difference of 911,000. This was an unusually large change, but major revisions to jobs numbers happen every year. In that sense, they are normal. The fact that they are normal, however, is itself strange. Why does the government still rely on creaky methods whose output takes so long to verify?

A great deal of official data are collected using samples of individuals, households, and business owners. The virtue of this approach is that randomly selecting respondents helps make the sample representative of the whole population. Over the past decade, however, household-survey-participation rates have dropped—a lot. Responses to the Current Population Survey, which measures a wide range of employment, demographic, and socioeconomic characteristics, fell from 88 percent in 2015 to 68 percent in 2025. Participation in the Consumer Expenditure Interview Survey, which collects data on household spending, plummeted from about 68 percent to 40 percent over the same period.

The problem is that the response rates are falling at different rates across the population, undermining the random-sampling benefits. For example, people with lower incomes tend to respond to surveys at lower rates than those with higher incomes, which skews official results. Recent Census Bureau research shows that after 2020, government surveys have overstated median household income by about 2 to 3 percent compared with alternative benchmarks that use IRS tax records. When fewer people—especially from harder-to-reach groups—respond to surveys, the picture we get of the “average American” gets fuzzier and less trustworthy. (The Trump administration’s rhetoric may drive those response rates even lower; what’s the point of responding if the data are presented as junk anyway?)

Another challenge is that the government needs to know which households and businesses to sample. A key reason for the recent large revisions to the jobs numbers is that the government has gotten worse at guessing which businesses are opening and closing (the so-called birth-death model). The idea of a random sample doesn’t really work if you’re not sure of the underlying population.

Lags in producing the statistics are another issue. Core government economic surveys, including the BLS jobs numbers, trail real-world shifts by months or even years. The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances—a vital source for understanding household wealth, assets, and debts—is conducted every three years, and results are released up to 18 months after collection begins. The 2025 survey results will not be available until late 2026. Similarly, even the initial estimate of quarterly U.S. GDP doesn’t appear until about one month after the quarter ends, followed by additional revisions over several more months.

As a result of these lags, policy makers may not be aware of crucial economic trends until it’s past time to act. During the global financial crisis, for example, official data such as GDP and unemployment were slow to reveal how bad the recession was. In December 2008, the National Bureau of Economic Research announced that the United States was in a recession—and in fact declared that the recession had started in December 2007, a full 12 months earlier. In line with these information lags, policy makers had hesitated to act decisively for much of 2008. As a result, the overwhelming majority of federal stimulus was issued in February 2009, about 14 months after the start of the recession. Earlier, forceful intervention could have provided much-needed relief to American households and prevented things from getting as bad as they did. During COVID-19, policy makers faced similar challenges. BLS data on business closures from the first year of the pandemic weren’t available until mid-2022. These lags made it harder to assess the scale of the crisis in real time.

One reason economic data take so long to collect and analyze is that the agencies responsible are not given adequate resources. Inflation-adjusted funding for statistical agencies fell by 14 percent from 2009 to 2024, resulting in staffing constraints and threats to vital programs. In recent years, budget shortfalls have led the Bureau of Economic Analysis to end dozens of key data sets, including those on self-employment by industry and county-level employment by industry. BLS has stopped collecting price data in about 350 categories for its Producer Price Index in 2025. It has also ended Consumer Price Index data collection in several localities and now surveys fewer outlets for the CPI because of staffing shortages. New budget cuts risk further weakening the quality and reach of official statistics—just as policy makers, markets, and the public depend on them most.

At the very same time, as the economy further digitizes, and the explosion in computing power makes it easier to collect and analyze data, we are witnessing an unprecedented surge of new data sources. Hedge funds and other investors focused on macro trends now actively use signals from payroll providers like ADP, consumer card transactions, and even satellite images to count cars in the parking lot of retail companies. The government could and should harness these same rich, real-time signals.

The government’s official housing statistics, for example, could benefit from more frequent updates and finer geographic detail. Redfin publishes new housing-market data every week. Its Homebuyer Demand Index measures activity by Redfin agents, providing real-time insights. Redfin’s home-value estimates are fairly accurate, reportedly within about 2 percent of the sale price on average for homes that are currently listed.

Real-time private data are especially valuable during a crisis. During the pandemic, the Harvard economist Raj Chetty’s Opportunity Insights tracker measured rapid changes in consumer spending, employment, and business activity, often weeks ahead of official reports. Chetty’s data used localized, real-time measures, such as payroll data and small-business operating statuses by zip code, to document the unequal recovery and to analyze how government stimulus and reopenings affected economic activity. Similarly, JPMorgan’s aggregated card-transaction data on millions of Americans provides highly detailed views of spending trends by geography, income bracket, and product category, enhancing our understanding of economic shifts as they happen.

Despite their promise, private-sector data sets raise important concerns about transparency, reliability, and continuity—issues that become even more crucial when considering their potential use in official statistics. In a survey of the leaders of all the major federal statistical agencies and senior statistical officials, most members agreed from experience that private data sources lack clear documentation, may require additional cleaning or manipulation to make them useful, and can suffer from poor quality or incompleteness. Some also cited a concern that private providers might abruptly discontinue publishing the metrics or move important metrics behind a paywall. The concerns with private data also extend to the potential for bias, as many private-sector data sets do not utilize random sampling, potentially making them susceptible to systematic errors and limiting their representativeness to the entire population.

Despite these potential issues, ignoring private-sector data is not a reasonable position to take. Thoughtfully combining the right metrics with public data can improve upon official statistics. For example, research has shown that combining the BLS jobs numbers with private data from ADP reduces the measurement error inherent in both data sources.

Many on the left may think that the Trump administration would never make a push for improved government data. But incorporating private-sector data into government statistics is exactly the type of change that advocates for technology-driven reform, including the tech wing of the MAGA movement, have been clamoring for—an opportunity for real improvements to government efficiency. Doing so could improve not only the credibility of official statistics but the foundations of policy, market functioning, and public confidence for years to come.