By Julian Owusu Abedi,Richard Dablah

Copyright thenewcrusadingguideonline

By Richard DABLAH

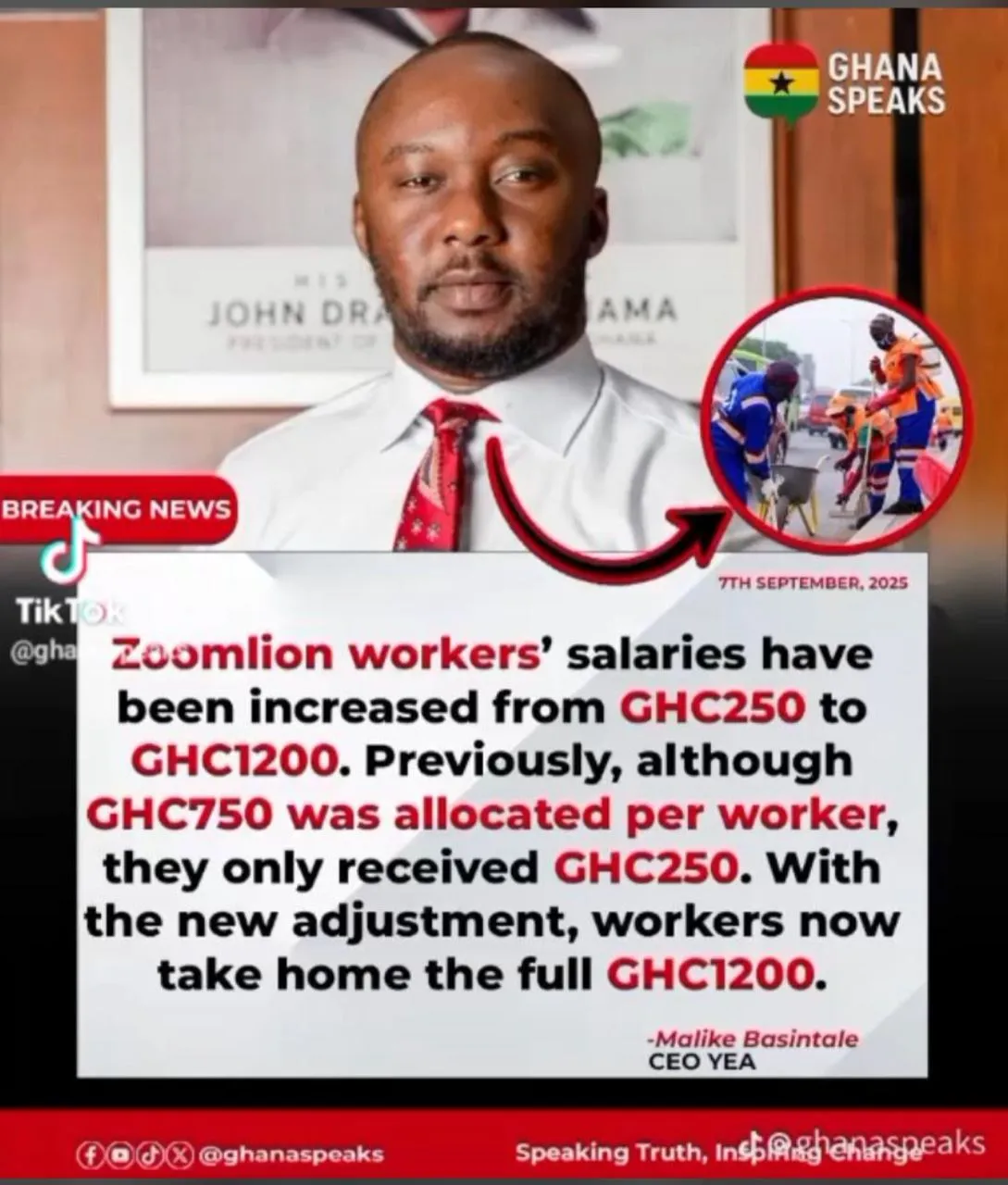

They tell the story as if the cheque changed everything: GHC250 to GHC1200 — a headline that tastes like justice. For men who sweep our streets and empty our bins, that cheque is relief folded into a fist. It buys rice that would not be bought otherwise; it buys a calmer sleep for wives and children; it buys a reprieve from the daily arithmetic of shame. Let it be said plainly: the payment matters. But the payment is a beginning, not a destination.

I watched the celebration and the quiet that followed. I watched the faces of younger collectors — hands stained with the city’s detritus, eyes bright with the odd mixture of gratitude and a hunger that is not simply about the next meal. They were relieved, yes. But beneath the relief sat a question many did not voice: how long will this last, and what will come after the next election cycle of headlines?

There is an ember in that cheque. It can warm a home for a night, or it can light something that lasts. Which depends less on the arithmetic of political promises and more on the choices of administrators, contractors, funders, and the workers themselves.

Consider how the world currently values this labour: invisible, delegable, easy to shortchange. Municipal budgets pay for removal; intermediaries pocket margins. The economics are perverse: the city pays for a service that destroys value rather than creates it. Waste is shipped out and with it any chance of local gain. We can do better. We must.

Start with a simple demand: make the books public. If the correction came from recovered funds, show the trail. Let payroll be digital and visible. Transparency is not virtue signaling. It is a way to stop leakage and to build trust so that the next step — converting part of municipal flows into seed capital — is plausible.

Next, imagine the workers not as passive recipients but as founders. Turn a fraction of the corrective payment into bridge capital for cooperative hubs. Equip them with shared machinery — grinders, presses, simple pelletizers — and with market-side guarantees: municipal offtake for pilot products. Compost for parks, plastic pavers for sidewalks, and recycled aggregates for minor municipal works. The city becomes the first buyer, not a distant creditor. This changes risk calculus for lenders and gives entrepreneurs a customer on day one.

Training must be short-cycle and market-driven. Teach people to make compost that meets agronomic standards; to pelletize plastic for construction use; to repair and refurbish household items for resale. Pair the technical modules with business coaching that treats the trainee as a potential owner — pricing, invoicing, simple ledgers — not as a casual recipient of charity. Seed grants should be modest but real; repay them through revenue-sharing so capital recycles without strangling early income.

Design matters: worker-ownership clauses in cooperative charters. Independent audits and rotating governance reduce capture by familiar middlemen. A covenant in municipal contracts — payroll transparency plus a small contribution to a local asset fund — ties corporate profit to community gain. Use national youth funds and CSR to match municipal redirections. Keep repayment tied to revenue, not to rigid amortization schedules that punish the first months of trade.

Do not pretend markets are automatic. They are fickle. Equipment will fail. Trainers will quit. So secure offtake before the hub spends a cedi. Bundle maintenance training into every purchase. Keep a spare-parts pool and an on-call technician. Measure success not by a ribbon-cutting but by the number of enterprises still trading after twelve months, by sales to municipal and private buyers, by the machines owned by cooperatives rather than by contractors.

There is a cultural work as well. Society applauds visible consumption — cars, phones, bling. We need to value making. Celebrate the first tonne of compost sold to a peri-urban farmer as loudly as a new apartment opening. Recognize cooperatives in civic ceremonies. Use municipal communications to change the signal attached to this labour: from shame to craftsmanship.

This is also a moral reckoning. If wages were previously diverted, the correction is partial restitution. Restitution carries responsibilities. It should not be a token distributed and forgotten. It should be a down payment on repairing a relationship in which workers were excluded from value creation. Turn the correction into an institutional promise: transparency, asset-building, and procurement that prefers worker-owned suppliers for small municipal contracts.

There will be resistance. Old gatekeepers will lobby. Short-term politicians will prefer headlines to hard work. Yet the costs of doing nothing are visible every morning on our streets: men and women with little to show at day’s end beyond a resealed packet of rice and the next day’s worry.

I keep returning to the picture of one young collector who laughed when I told him he had already broken family records. Laughter that sounded like pride and disbelief in the same breath. Imagine directing that pride toward owning the press that makes the pavers for his own neighbourhood. Imagine bylaws that prefer worker-owned firms for small contracts. Imagine markets that do not merely buy removal but buy transformation.

The cheque that moved wages can do two things at once: it can bring immediate relief and seed a different future. The choice is both political and practical, as well as ethical and strategic. Will we let the usual actors reap the profits, or will we insist that workers keep what they build? The ember in the cheque waits for someone to breathe on it.

Audentes fortuna iuvat.