On Sept. 10, we saw the fatal shooting of Charlie Kirk, the founder of a right-wing youth movement, as he spoke at Utah Valley University.

Political violence is appalling, and recent events have underscored just how devastating it can be. But amid the understandable fear and anger, it’s worth remembering that most Americans, regardless of political affiliation, abhor political violence.

I have researched, written, and taught for over a decade on the subjects of partisanship and public opinion, and more recently, political intolerance. In my work, I’ve seen how easy it is to fall into the trap of assuming the worst about those we disagree with — especially in times of uncertainty and upheaval. I’ve also seen that those assumptions can be challenged. I think it’s essential we do so.

The last few years have given us too many reminders that acts of political violence strike at the heart of our democracy. We’re reminded of the January 6th U.S. Capitol attack, assassination attempts on President Trump in 2024 and the murder of Minnesota state Rep. Melissa Hortman in a targeted political shooting earlier this year. These acts, so widely publicized, can make it easy to believe that political violence is growing normal in our society.

Support for political violence remains extremely rare, however. When survey questions are carefully worded to clarify what “violence” entails, only 4 to 5% of Americans are likely to say they support it. The Polarization Research Lab, a nonpartisan collaborative effort among scholars from Dartmouth College, Stanford University and the University of Pennsylvania, finds that just 1 to 2% of Americans say they support politically motivated murder . Yet partisans estimate that about one-third of the other side holds such views, an enormous and dangerous overestimation. Early evidence suggests that events like the 2024 assassination attempt on candidate Donald Trump may even reduce public support for political violence in their aftermath.

That’s not to ignore the danger of the moment. As Nathan Kalmoe and Lilliana Mason warn in their book Radical American Partisanship, even small increases in approval for political violence can create an atmosphere where the most extreme actors feel emboldened.

But our misperceptions can become self-fulfilling. When partisans believe the other side is willing to undermine democracy, they become more willing to do so themselves. In other words, fear can breed justification. Researchers call this the “Subversion Dilemma.” People who deeply value democracy may still support anti-democratic actions if they believe those actions are necessary to stop the other side first. For instance, fueled by persistent false claims that Democrats had “rigged” the 2020 election, Republican officials in multiple states attempted to delay certification or send alternate slates of electors.

But we can avoid this spiral into political violence. When people have accurate information showing that most Americans–even those across the aisle–reject violence and uphold democratic norms, they may become less willing to tolerate violence from their own side. Simply knowing that our fellow Americans don’t want to tear the system down can strengthen our collective commitment to preserving it.

We should be cautious in forming judgments about our political opponents based on posts from anonymous social media accounts or commentators who amplify them for attention. These voices are unrepresentative and distort the reality of public opinion. Instead, we should rely on data that show America in the aggregate, revealing far more restraint and democratic commitment than those voices suggest.

We can also look to real-world examples that showcase a commitment to common democratic principles. We have an example right here in Utah. Gov. Spencer Cox’s “Disagree Better” initiative began during the 2020 gubernatorial campaign when he partnered in an ad with his Democratic opponent, Chris Peterson. They committed to promoting civility in political discourse and to accept election results. In research I conducted with dozens of other scholars studying polarization and antidemocratic attitudes, we found that this bipartisan effort is among the most effective ways to reduce support for political violence. Cox’s initiative has since expanded nationally through the National Governors Association. Our research showed that this lesson from Utah can have broader applicability across the United States.

Let’s keep the facts in mind. Isolated extremists are driving political violence in America, not large groups. Sweeping generalizations about political opponents do more harm than good. They feed the false narrative that the “other side” is inherently dangerous when in fact, most people value peace and democratic principles. And in moments of emotion and provocation, it helps to pause. In a media environment that rewards outrage, taking time to reflect and step offline can contribute to healthier public discourse.

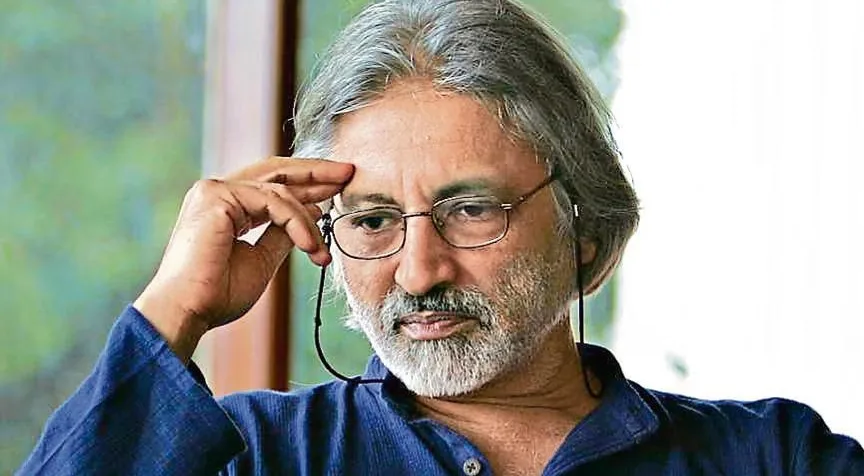

Ben Lyons is an associate professor of communication at the University of Utah. He co-authored “Megastudy testing 25 treatments to reduce antidemocratic attitudes and partisan animosity,” published in Science in 2024.