By Susan Mansfield

Copyright scotsman

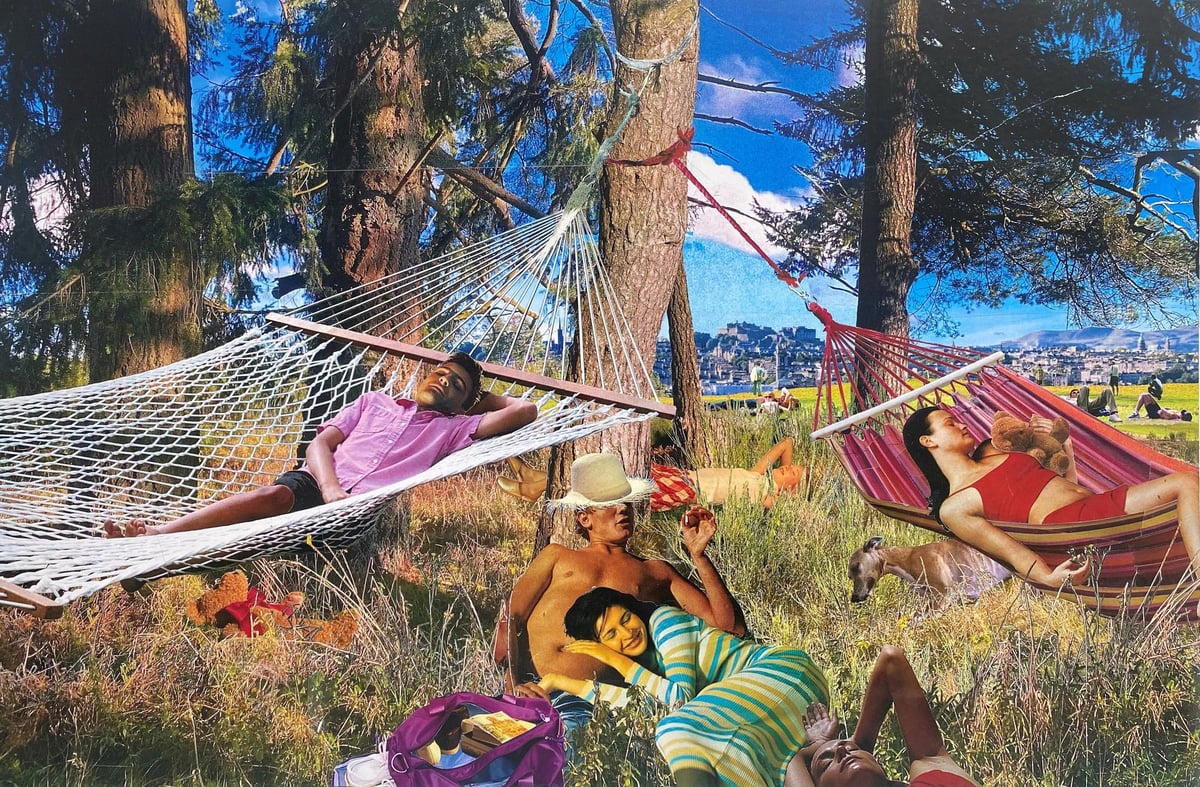

David Mach is trying to think of a word which has escaped him. It sums up the person he is in the art world. “Interloper” is almost it, “maverick” might work, so might “troublemaker”, but none of them is quite right. “I feel like I live on a ridge around the town. I ride around it on horseback and occasionally I go in to the centre, but I always go out to the ridge,” he says. “That seems to be where I exist.” Fife-born Mach is known for his large-scale sculptures, works that demand attention: a temple made of tyres, a cascade of tumbling phone boxes, the Big Heids on the M8, the monumental crucifixion scene that fronted his 2011 show at Edinburgh’s City Art Centre, Precious Light. He can be outspoken, can ruffle feathers in institutions like the Royal Academy, of which he is a member. He’s a whirlwind of energy, capable of pushing forward big projects by the sheer force of his personality. “The thing isn’t going to happen by itself, you’ve got to drive it forward. F***ing make the effort, that’s the secret of life.” Four years ago, Mach moved back to Scotland, having lived in London since he studied at the Royal College of Art, and now lives in Fife, a few miles from Methil where he grew up. He and his partner, artist Lyndsey Gibb – he tells me they got married a few weeks ago – have a two-year-old son and another baby on the way. For the first time, he’s making work in and about Scotland. “I like being here. I don’t think you can leave Scotland. It’s a thing that’s embedded in you. People have opinions about the Scots, especially in London. I liked that. It enabled me never to become part of an establishment.” He’s also been wearing out shoe leather introducing himself to Scottish galleries. “I actually went round a few and said, ‘Hey, I’m in Scotland, do you fancy doing a show?’ I’ve never really shown here, because I was always in Tokyo or San Francisco or wherever. I felt that I should show people what I’m doing, introduce myself – again.” One result of that is Sunshine on Leith, an exhibition of collages opening on 26 September at Edinburgh’s Open Eye Gallery. His subject is mainly Edinburgh. A half-made collage of the Grassmarket is on his work table. He wanted to run a Formula One track through it, but it isn’t working. Now he’s got two days to find an alternative. Mixed-media collage quickly became a key aspect of Mach’s practice: it began as a way of presenting ideas for sculpture but then took on a life of its own. Bright and bolshie and often big, the works juxtapose landmarks, people and pop culture references; his shelves are lined with labelled files of images: reptiles, Medusa, holograms, people looking up. Weather often plays an important role: a tropical beach scene at Portobello, ice-skating on the Water of Leith, tourists lounging in hammocks at the foot of Castle Rock. They’re meticulously worked. A big one can take weeks, even months. “People say, ‘You do these on computer don’t you?’ No! I don’t do anything on computer because you’ll get a second-hand version of what you actually want. You’re better doing it with a pair of scissors and a little plastic tube of Pritt, having gone through 1,000 magazines looking for a particular image.” READ MORE: Art reviews: Photo Dalkeith | Matthew Arthur Williams In another Water of Leith scene, the water next to the floating Fingal Hotel has been turned into a thermal spa “a la Rekjavik”. “A bit like you want Scotland to do, really, soup it up a bit. Some billionaire could move into Leith, drain that bit where the ship is, heat it. They’re like schemes in a way, these collages of mine, they’re ideas for how you could do something.” He’s thinking about that word again, tapping questions into his phone. “We’ll find that word yet. My dad told me it was one of the best things you could be. You’re on the inside, but you’re not actually one of them. You don’t have to kiss anybody’s arse.” Mach used to have an army of assistants making collages for him. At its busiest, his London studio employed 40 people. “We were pulling in relatively large sums, but when I asked my PA how much money we had she said minus £35K. I couldn’t keep up with the machine.” Now, he prefers to work differently, just him and his scalpel, hiring local teams to realise big projects. The ideas, though, are as big as ever. “The work is still as dynamic and scary as it ever was, and there’s almost as much of it as well. I feel ridiculous, actually. I’m going to be 70 next year, for f***’s sake, I still feel like a 25-year-old trying to make his way in the art world. I don’t worry about very much, but I do think maybe I’m a bit of a twit because you have all these grand ideas for things, and who the hell asked you? That’s a very Scottish thing. But that’s how things happen: somebody does something.” The sense of scale, he says, came from growing up in Methil, then a town of big industries: the docks, the mine, the power station, the oil-rig assembly plant. “I was outrageously lucky to grow up in Methil. I remember the day half a leg of an oil platform went past our house. Half a leg, on two 40-foot trucks. Then I got the bus up to Dundee for art college and there’s a guy making something out of metal which is about the size of a bike and saying: ‘Look at the size of this!’ I’m trying to be happy for the guy but I’m thinking ‘it could be bigger than that.’” READ MORE: Art reviews: Paula Rego | Ten Modern Scottish Masters | Jim Dunbar He talks about how the art world has become too safe, resting on its laurels in the fat years when it was making plenty of money. He’s going to war against blandness, talking about sculptures in which gallery walls explode, or a tornado rips through the floor. A big gallery in London nearly went for the exploding wall idea, he says. He’s hopeful that someone else will. He has dreamed up some of his biggest ever schemes in the last few years, architectural projects made of shipping containers: a multi-purpose venue in Edinburgh Park, a university building in Damascus, an icon the height of the Eiffel Tower in Mauritius. For a variety of reasons – recession, pandemic, war – none has yet been built. “I like pissing architects off. ‘What? You’re making a building? How dare you?’ There is a bit of that. That seems to be my job, actually, pissing the art world off, in a way.” We’re back with the word. Mach goes off to consult Lyndsey, then comes back. “Infiltrator! If you don’t infiltrate the system, the business, the government then nothing good is going to happen. A spanner in the works when needed. Isn’t it funny that an infiltrator can be a spanner in the works when needed, and can be a supplier of the idea which makes things work when needed as well?” David Mach: Sunshine on Leith is at the Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh, from 26 September until 18 October. This feature was produced in association with the Open Eye Gallery. The Scotsman’s arts newsletter is now sent twice a week – subscribe today