Where the school had been, moments before, was a cloud of dust.

The day was pleasant and partly cloudy in Mexico City when a 7.1 magnitude earthquake shook the earth, killing around 400 people. Of those, about 30 of the dead were inside the Enrique Rebsámen school, where the brittle, unreinforced concrete structure buckled and pancaked.

Neighbors and parents rushed to the area, spending hours pulling children, some alive, many dead, from the rubble, each one a miracle or a tragedy.

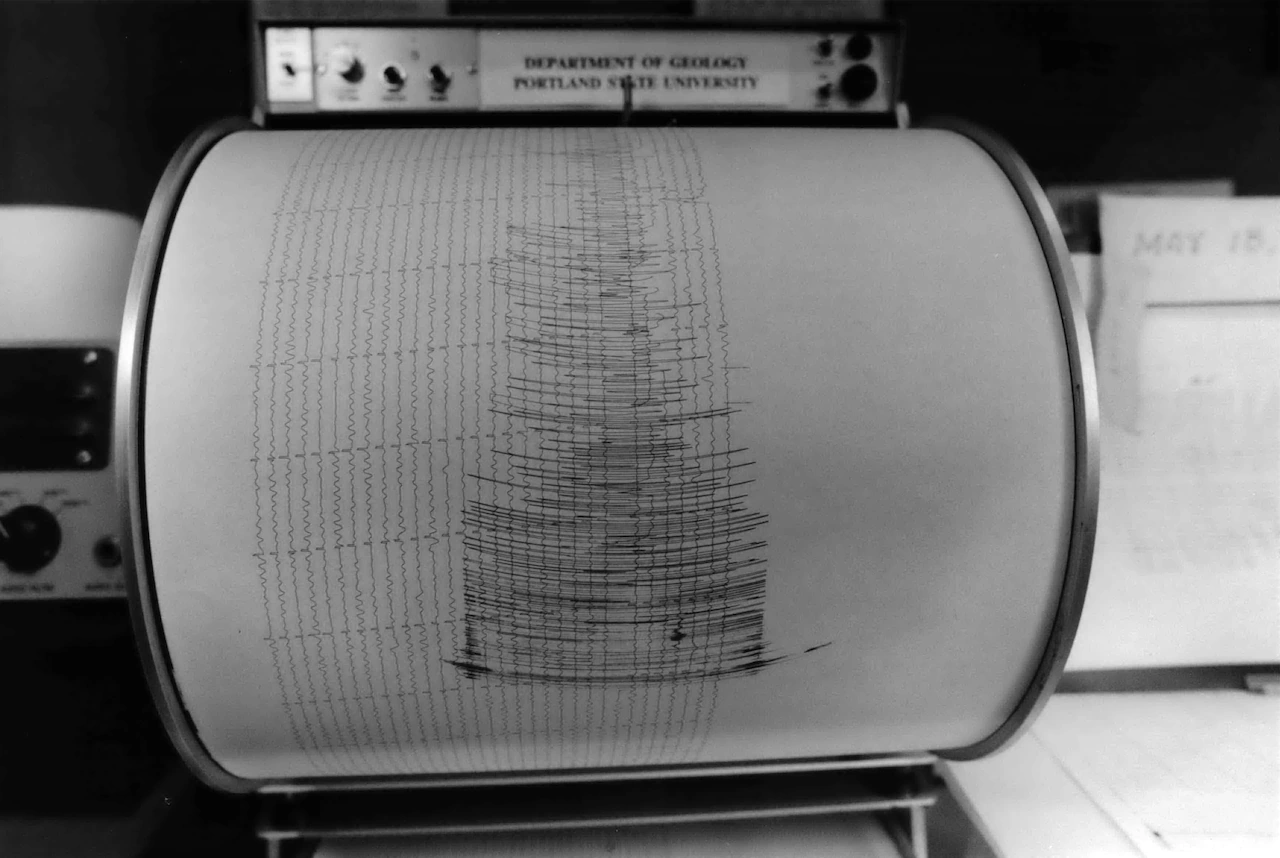

An earthquake is coming for the Pacific Northwest, possibly much bigger than the Puebla earthquake of 2017. But even a smaller earthquake could do real damage.

Aging infrastructure means “many hundreds” of kids could die if a major earthquake hit the Portland area during school hours, according to Yumei Wang, a civil engineer and faculty adviser who works on resilience and disaster preparedness at Portland State University.

With Portland-area students back in schools, some of which were built more than 100 years ago, the question remains: What will it take to make sure Oregonians don’t find themselves in the place of those parents in Mexico City, pulling children from crushing brick and concrete, desperately hoping for a miracle?

The Oregonian/OregonLive reached out to 21 districts in the Portland area and requested records on seismic safety. Newsroom analysis found that in the nearly 20 years since the state did a large-scale examination of building safety, of the 138 schools considered at “high” or “very high” risk of collapse in 2007, 110 were still operating as schools in 2025. Of those, 55 have had no major seismic retrofits since the study was completed.

See how schools in 20 Portland area public school districts rated in 2007 and what work has been done to address seismic issues here:

…

For more than four decades, geologists have been sounding the alarm that a big earthquake is coming.

In the mid-1980s, geologist Brian Atwater theorized that a huge earthquake killed cedars in a tidal marsh along the Copalis River in Washington, creating a “ghost forest.” Further researchers found that the last major Cascadia subduction zone quake, estimated at a 9.0, happened on Jan. 26, 1700, causing the Pacific coastline in the Northwest to drop several feet and sending a tsunami to Japan.

Chris Goldfinger is a professor emeritus at Oregon State University who studies marine geology, geophysics, paleoseismology and subduction earthquakes. Goldfinger was in Japan at an earthquake conference when a 9.1 subduction zone quake hit in 2011.

A magnitude 9.0 earthquake striking the Northwest has taken on “a sort of mythical gigantism,” Goldfinger said. People believe it will be “like an asteroid; there’s going to be nothing left but a smoking crater. And that’s not true at all.”

The reality is much more complicated.

Portland could be hit by any one of three different kinds of earthquakes, Goldfinger said. The subduction zone quake coming from the coast; an earthquake from the descending slab underneath the Pacific Northwest, like the 6.8 Nisqually earthquake in Seattle in 2001; or an upper plate earthquake, like the Scotts Mills earthquake of 1993.

All could cause damage, the extent of which will mostly be determined by the strength and length of the shaking.

The possibility of “The Big One” gets a lot of attention, but some scientists estimate that a 6.8 earthquake on the Portland Hills fault could cause more damage than a large Cascadia quake, though it is less likely to happen anytime soon.

According to Goldfinger, Portland’s chance of a damaging earthquake in the next 50 years is about 20%-22%. The chance the area will be hit by a magnitude 9.0 or bigger quake in that timeframe is 10%-15%.

Buildings built in a time before earthquakes were known to be a genuine threat to the Pacific Northwest were built to withstand two things, Goldfinger said: their own weight and the wind.

Many of these old buildings are constructed from unreinforced masonry, made of brick, concrete, stone or clay. Portland used to maintain a database of more than 1,500 unreinforced masonry buildings within city limits, including schools, before it was taken down in 2020 after pushback from groups that said the database was inaccurate and shamed building owners who couldn’t afford to retrofit their buildings.

Now, that list is only available through a public records request.

In 2024, Portland Public Schools published a list of 23 unreinforced masonry schools that “are not yet fully seismically reinforced as of 2024.” In September, the district publicly shared a report that rated the seismic risk of individual buildings in the district from 1 to 10, with 10 being the most dangerous. According to that report, 38 schools have at least one building part rated a 9.0 or higher.

Oregonians who have been around a while may already know what kind of damage even a smaller earthquake can do to old, brick buildings.

In 1993, the 5.6 Scotts Mills earthquake hit the Willamette Valley at around 5:30 a.m., causing parts of brick-faced walls at Molalla High School, built in 1926, to collapse. The Scotts Mills quake, also called the “spring break quake,” only resulted in six injuries statewide, but it’s impossible to know how many students, teachers and staff could have been hurt or worse if it had happened during school hours.

Unreinforced masonry isn’t the only issue. Concrete structures built before modern codes would “come apart and then you get this pancake stack coming down,” Goldfinger said, which is just as dangerous as a collapsing unreinforced masonry building.

Oregon has been trying to address the problem of unsafe buildings and infrastructure for many years.

In 1974, the state implemented its first statewide building code, which included provisions that buildings be designed with seismic safety in mind.

As science progressed, so did building codes. Through the late 1980s and into the late ‘90s, Oregon established more specific rules to keep people safe in an earthquake.

In 2004, Oregon switched from the Uniform Building Code to the more stringent International Building Code, which was also much more specific, considered a longer earthquake recurrence interval and looked at site characteristics like location and soil type.

Then, in 2005, the Legislature passed Senate Bill 2, which directed Oregon’s Department of Geology and Mineral Industries to complete a rapid visual screening study of all school and emergency services buildings in the state.

It’s a triage method, essentially, based on building type, materials, construction date, soil type and seismic zone.

“Rapid visual screening is a technique developed to evaluate a large number of buildings quickly,” said Lalo Guerrero, a geology hazard specialist at Oregon’s Department of Geology and Mineral Industries. “It is a first-order seismic hazard assessment because it relies entirely on the external characteristics of the building as seen from the outside.”

“A complete hazard assessment for an individual building requires a structural evaluation by an engineer,” Guerrero said. “One of the benefits of RVS is that it helps triage and identify which buildings require further internal structural assessment.”

The report was a massive undertaking and included a screening of 3,352 buildings. Each building was awarded a “collapse potential.” The state geology agency released the findings in 2007.

Most districts in the Portland area had a few schools listed as having “high” or “very high” collapse potential, but one district stood out. In 2007, out of 90 Portland Public Schools buildings on the list, nearly 40 had a “high” or “very high” collapse potential.

The report was intended to be the first step toward reducing risk in the state.

“Ideally,” Guerrero said, “this type of seismic assessment would be performed at least once every 10 years as part of ongoing resilience and emergency planning purposes.”

In Oregon, it’s been almost 20 years.

Instead, school districts and education service districts are required to provide the department “with notice of construction projects that may affect a school’s seismic risk.”

Those reports are due by Sept. 30 each year and are posted online with the original 2007 assessment.

Districts put varying degrees of work into the reports. Many are one-page notices that no work has taken place.

The reports online haven’t been updated since 2019, due to staffing issues, the pandemic and a change to the process, Guerrero said.

While the reports are required by statute, Guerrero said, “There are no stated mechanisms or consequences for schools that do not provide updates.”