By Bloomberg

Copyright scmp

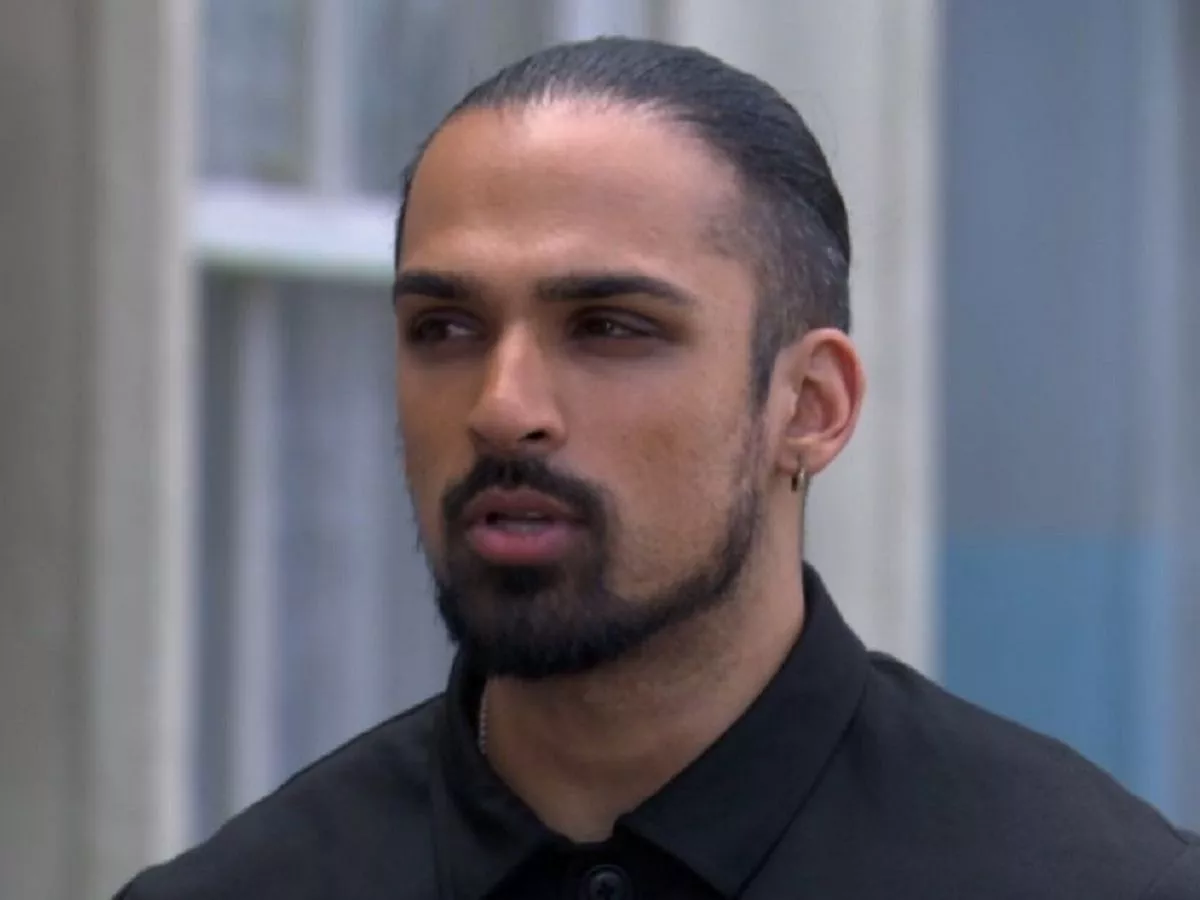

Raden Igun Wicaksono has a warning for Indonesia’s leaders: the fight is just getting started.

The chairman of one of the country’s largest motorcycle taxi associations has promised “greater and greater escalation”, warning that millions of drivers are ready to ignite what he calls the ojol revolution, “ojol” being a shorthand for motorcycle taxi drivers booked through apps like Gojek or Grab.

Just weeks ago, Wicaksono and his fellow workers joined students and labourers and helped force lawmakers to scale back official perks and oust some politicians from parliament. On Wednesday, thousands of drivers will be back at parliament again, demanding laws that protect gig workers who keep Southeast Asia’s biggest economy humming.

That fight has turned almost 2 million motorcycle taxi drivers into President Prabowo Subianto’s newest political liability. They are visible in every traffic jam and at every street corner, clad in the green uniforms of Gojek and Grab. They are also poorly paid, largely uninsured and increasingly angry at the government, blaming it for its long-standing failure to create enough secure and well-paying jobs for the country’s growing workforce.

“We are ready to be the trigger for another revolution in Indonesia because millions of our peers are no longer able to live a decent life,” said Wicaksono, chairman of Garda, a drivers’ association with almost 7,000 members that is organising the protest.

Motorcycle taxi driving was supposed to be a stopgap for the jobless. Instead, it has become a national symbol of what economists call Indonesia’s employment crisis: 59 per cent of workers are stuck in the informal sector, grinding long hours for little pay and virtually no security. A Gates Foundation-backed study estimates drivers earn just US$163 a month in Jakarta – half the city’s minimum wage.

The drivers’ anger is rooted in promises broken by successive governments. “Every president and vice-president has pledged to create jobs,” said Wicaksono. “But this has never happened. Young people who should be getting decent formal jobs end up becoming motorcycle taxi drivers. And they are ignored.”

The number of informal workers in Indonesia exploded during the Covid-19 pandemic, from about 71 million people, or 56 per cent of the population in 2019, to 87 million people this year.

Motorcycle taxi drivers rose to 4.2 million last year from 3.62 million in 2019, yet just 12 per cent are registered as participants in social security for employment, according to a study. Almost one-fifth of drivers reported being unable to meet basic household expenses, according to the Gates Foundation-backed study.

Last month’s protests, ignited by fury over perks for politicians, quickly turned violent after the death of a 21-year-old delivery driver in Jakarta, who was run over by a police vehicle on August 28. What followed was unrest across the country as government offices were set alight and politicians’ houses were looted. Such deep and broad anger over inequality set these protests apart from previous demonstrations and also highlighted the perilous economic conditions of the millions of gig workers in Indonesia.

“Drivers represent a class that lives hand-to-mouth,” said D. Nicky Fahrizal, researcher at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Jakarta. “They are the backbone of the middle class in everyday life. Therefore, it sparked anger across social classes.”

Aryanti Prihatin Ningrum, 42, has worked as a Grab driver since 2020 after a porridge shop she used to run on the outskirts of Jakarta went bankrupt during the pandemic. She works to feed her three children, including 19-year-old son Damar Arya Pratama, who has also been working as a Grab driver for the past two months. Her economic future lies not in herself, but in her son Damar.

“What I really want is Damar to go to university,” she said. “My hope is that he can become successful so that, as I get older, he can take care of his younger twin siblings.”

Yadin, a 48-year-old father of five children, moved from his previous work in the food and drink business to become a motorcycle taxi driver in the hopes that pay would be better. It has not been.

“For us, motorcycle taxi driving was a last resort job,” said Yadin, who goes by one name. “We work through rain and sun for our families. We just don’t want to be mistreated by authorities and operators.”

Gojek and Grab spokespeople did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

In the past decade, motorcycle taxi drivers have built parallel networks that look a lot like unions: shelters, traffic alert groups, even insurance, all coordinated through WhatsApp. Those same networks can summon tens of thousands to the streets with little more than a forwarded message.

Indonesian motorcycle taxi drivers are among the most active protesters among gig workers globally, according to the UN’s labour body. That capacity for disruption has Prabowo scrambling. His ministers are rushing out welfare assistance, such as discounted insurance premiums and new benefit schemes.

Meanwhile, lawmakers dither over legal protections for gig workers. Economists warn that if the government stalls, unrest could metastasise into something far larger.

These legal protections are “like a safety valve”, Fadhil Hasan, an economist at the Institute for Development of Economics and Finance in Jakarta, said in an opinion article. “The government would be quelling the growing restlessness among gig workers that, if left unchecked, can transform into large-scale social unrest.”

For Wicaksono, large-scale social unrest is exactly what he is preparing for. He expects about 2,000 to 5,000 people to turn out on Wednesday. While that is a much smaller number than his estimate of 50,000 motorcycle taxi driver protesters in Jakarta last month, Wicaksono says he plans to organise bigger protests in the months to come.

“This is something the government should be concerned about,” he said. “Ojol could trigger a revolution in Indonesia.”