It might seem crass to reduce the work of Robert Redford, who passed away on Tuesday at the age of 89, to a few conversation scenes in a handful of movies. But if there’s one easy way to spot the greatness of one of Hollywood’s greatest of all actors — not to mention director, producer and godfather of modern independent cinema through his Sundance Institute — you only need to watch how he handled himself on the telephone.

Let’s start with a major performance in what’s easily one of the best films he starred in: Alan J. Pakula’s 1976 Watergate classic All the President’s Men, a project Redford nurtured from the start, acquiring the rights to the book and overseeing much of its development. As Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward, the actor starred opposite Dustin Hoffmann as a calm, collected but absolutely relentless truth-seeker who stumbles onto a story he won’t let go of, pursuing it until he winds up taking down President Nixon himself.

In the film’s most crucial scene, Woodward sits at his desk, picks up the phone, and, as any good journalist should do, follows the money. Pakula shot the sequence in a single five-minute take, using a split-diopter lens so that Woodward remained in focus in the foreground, while his Post colleagues are in focus in the background as they watch the 1972 Democratic National Convention on TV. The camera ever-so-slowly tracks in on Redford’s face as his character finally lands the big lead that will crack the whole case, blowing open the Watergate investigation and changing the course of American history.

And this is where the actor’s brilliance comes through. Redford understood, as all the best actors have, that a great film performance is sometimes more about listening than speaking. It’s about how they receive information and process it on screen for the viewers who identify with them. The less the star does, the more we relate to what they’re doing, so that each small action is amplified by the camera until it becomes grandiose.

Redford never had a motto, but “less is more” would have been a good one. The way he uses his eyes in that scene, registering the truth as it slowly comes out, is unparalleled. And that gesture of gratitude he makes when his contact on the phone says: “I know I shouldn’t be telling you this …”, as if Woodward were thanking the gods themselves for the gift they’ve just dropped into his lap, says more about what’s about to happen — both to his career and to the country as a whole — than any words he could have spoken.

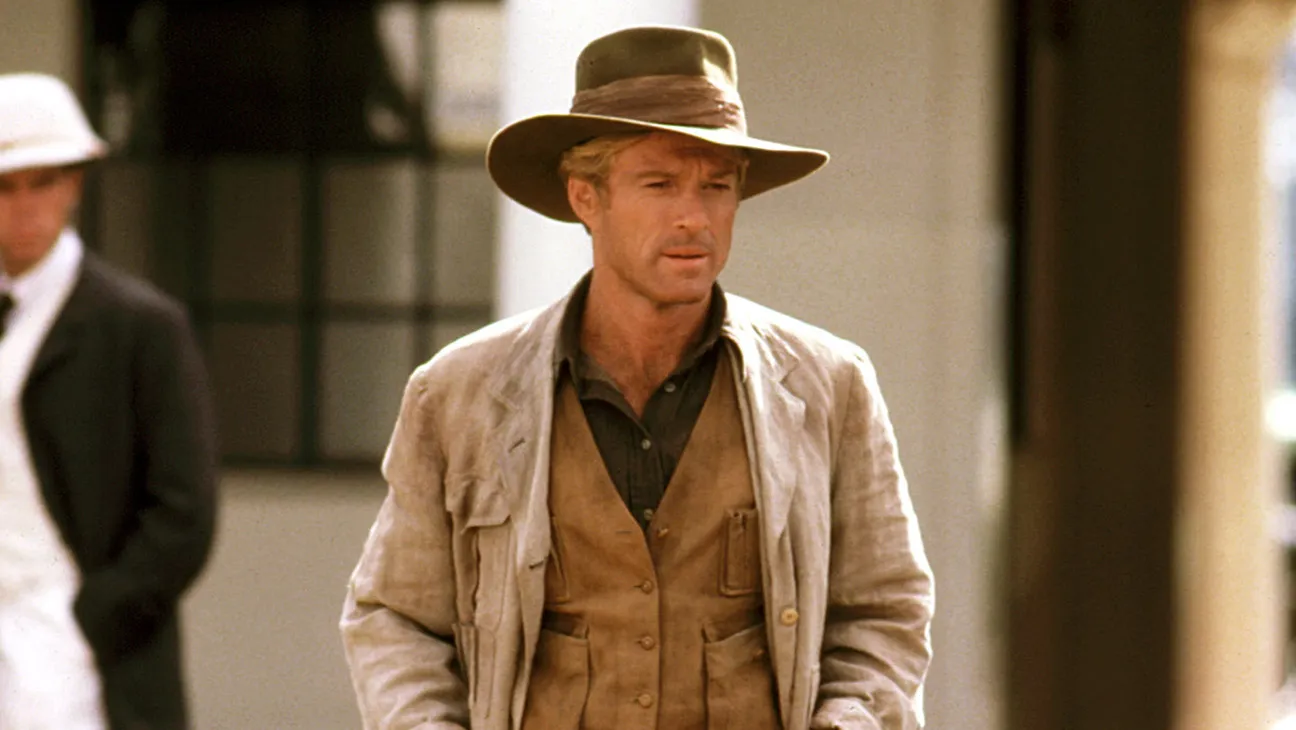

Few would deny that the actor was one of the most gorgeous men to ever play in the movies. If you need proof of what “jaw-dropping” means, check out the still of him and Paul Newman in Butch Cassidy in the Sundance Kid, published along with THR’s obituary.

But what made Redford special was how his beauty concealed something dark and anxious at the heart of his most memorable characters — a complexity that spoke to the turbulent times in which he rose to stardom, from the late 1960s to the mid 1970s. His reassuring golden-boy demeanor belied something sinister that was eating America from the inside, during a period rife with political unrest, assassinations and conspiracies.

Which brings us to another great feat of less-is-more acting, and another great phone scene. In Sydney Pollock’s masterly 1975 thriller, Three Days of the Condor, Redford plays a nerdy CIA analyst on the run after his entire New York office is gunned down by a hit squad. His character, whose codename is Condor, is out buying lunch at a coffee shop when the massacre happens. He comes back to discover the bloodbath, grabs a gun and takes off, rushing to the nearest phone booth to call into headquarters.

The conversation is also captured in one take, intercut with a robotic CIA operative giving Condor instructions on the other end of the line. But Redford projects something far different than in the Pakula film, though here as there, he does it almost exclusively with his eyes, as well as just a handful of words.

The mood this time is one of confusion and a total lack of control — the world is falling apart and Condor’s about to get swept away with it. “Are you damaged?” the agent coldly asks. “Damaged … ? No,” he responds. And the way Redford delivers that “no” manages to convey two complex ideas at once: that his character has just come to terms with the fact he’s escaped death purely out of luck, and that he’s going to have to hone his survival instincts if he wants to stay alive.

The combination of raw confidence and existential fear is something Redford conveyed better than any other actor of his time. Unlike Dustin Hoffman or Al Pacino or Robert De Niro, who excelled at portraying loners, weirdos or psychopaths — outsiders trying and often failing to make it to the inside — Redford was at his best when he played self-assured inside men who risked slipping to the outside, in a nation that seemed to be losing its way. His characters were thoughtful, resolute, at times heroic, but they were usually fighting losing battles.

This brings to mind another vintage Redford moment — not a phone scene per se, but one where he’s again isolated within the frame, talking into a microphone and doing more with gestures than words. It comes towards the end of Michael Ritchie’s 1972 political satire, The Candidate, in which the actor plays idealistic Democratic hopeful Bill McKay, whose deep-seated political beliefs are chipped away by a campaign he gradually loses his grip on.

Whisked into a TV studio to record a free on-air spot before election day, McKay sits down under the lights and gets ready for his speech. When the camera rolls, he starts laughing and can’t stop. They try a few more takes, but he ruins all of them. It seems to be a light moment, and Redford plays it so effortlessly that it looks real, as if he were messing up the takes of the movie itself. Yet what the scene says is significantly darker: Politics in America have become so absurd that even an honest and promising candidate like McKay will crack in the face of such absurdity, losing the core of his convictions even if he winds up winning the race.

In real life, Redford was a man filled with strong political convictions, defending causes like the environment, LBGTQ and Native American rights — and of course independent movies through Sundance, which he founded in 1981 on land he bought with his proceeds from Butch Cassidy and the ski flick Downhill Racer, also directed by Ritchie.

But as arguably the most famous Hollywood leading man of his time, he tended to shun the spotlight. He turned to directing in 1980 with the brooding family drama Ordinary People, which wound up sweeping the Oscars over the likes of Raging Bull. Many of the subsequent films he helmed were marked by the pessimism that characterized his work as an actor in the ’70s, whether the stories were about New Mexican farmers (The Milagro Beanfield War), a TV scandal in the 1950s (Quiz Show) or a botched U.S. military operation in Afghanistan (Lions for Lambs).

He acted much less in his later years, preferring to work with familiar directors like Sydney Pollack (Out of Africa, Havana) or young auteurs like David Lowery (The Old Man & The Gun, Pete’s Dragon) who broke through by showing their films at Sundance. And sometimes he did money jobs like the Russo brothers’ Captain America: The Winter Soldier, though even that Marvel blockbuster made several nods to the conspiracy movies that marked Redford’s career decades earlier.

The actor’s greatest final performance was also a throwback to what he did so well in his heyday: building emotions out of pure looks and gestures rather than traditional dialogue. In J.C. Chandor’s 2013 seafaring saga All is Lost, Redford starred by himself — and it would seem at times, as himself — in a nearly mute performance as a sailor cast adrift on a tiny boat in the middle of the Pacific, fighting to survive with the odds stacked against him.

He was 77 years old by then, but he still channeled much of the charm and ruggedness, coupled with all the angst and disquiet, of his youth, again playing someone whose heroism meant little in the face of an unforgiving world. The movie has some Hollywood twists to it, but it often feels more like a documentary whose subject is Redford himself.

The film is another great example of the actor doing a lot with a little. Just witness how he soothingly gulps down a scotch after having what looks like a minor heart attack. How he wakes up one morning to find his boat sinking further into the deep, in which case he calmly grabs his life raft and abandons ship. How he sits on that raft in a middle of a vast and hopeless ocean, quietly studying his navigational tools to see if he can somehow find a way to save himself. Each gesture is simple and pared down, but it’s also a matter of life or death.

That movie could have also been titled The Old Man and the Sea, which makes sense because like many of Ernest Hemingway’s heroes, Redford was most memorable when he was portraying men of few words, or sometimes of no words at all. They were gorgeous men, but you could see it in their eyes that they were wracked by the ugliness of fear and loss. Perhaps that’s what it means to be an American icon on the level that Redford was: to be able to project so much beauty and charisma, so much vigor and charm, and yet show that there something was wrong beneath the surface — if you just looked at him closely enough.