By Rick Porter Stephen Galloway

Copyright

Skip to main content

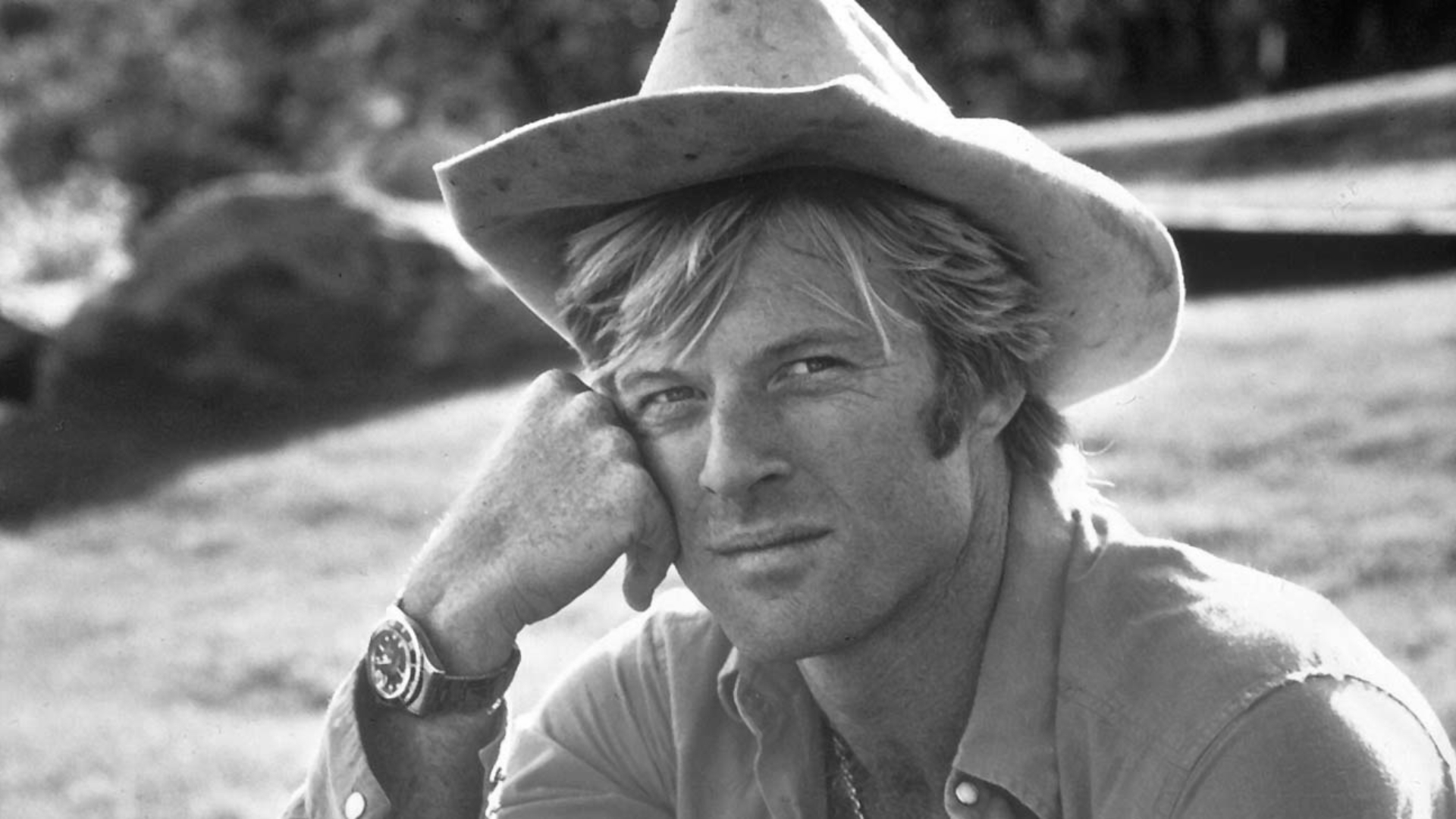

Robert Redford, Golden Boy of Hollywood, Dies at 89

September 16, 2025 5:32am

Share on Facebook

Share to Flipboard

Send an Email

Show additional share options

Share on LinkedIn

Share on Pinterest

Share on Reddit

Share on Tumblr

Share on Whats App

Print the Article

Post a Comment

Robert Redford

Courtesy of Photofest

Share on Facebook

Share to Flipboard

Send an Email

Show additional share options

Share on LinkedIn

Share on Pinterest

Share on Reddit

Share on Tumblr

Share on Whats App

Print the Article

Post a Comment

Robert Redford, the Hollywood golden boy and Sundance Film Festival founder who starred in such movies as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Way We Were and All the President’s Men — and who won an Academy Award for directing Ordinary People — died Tuesday. He was 89.

Redford died in his sleep at his home outside Provo, Utah, his longtime publicist, Cindi Berger, confirmed to The Hollywood Reporter.

The actor-producer-director, a four-time Academy Award nominee and honorary Oscar recipient, was one of the few truly iconic screen figures of the past half-century, the avatar of a certain kind of all-American ideal who nonetheless took a dyspeptic view of his country in several notable dramas including Downhill Racer (1969), The Candidate (1972), Three Days of the Condor (1975) and All the President’s Men (1976).

Related Stories

Paula Shaw, Actress in ‘Freddy vs. Jason’ and Hallmark Holiday Telefilms, Dies at 84

Patricia Crowley, Star of TV’s ‘Please Don’t Eat the Daisies,’ Dies at 91

He brought his good looks, ineffable charm and romantic appeal to heroes as well as antiheroes, from one of the outlaws in Sundance Kid to the Nixon-toppling journalist Bob Woodward in All the President’s Men to the well-meaning but naive political contender Bill McKay in Candidate. His sheen often contrasted with the jaundiced view of his pictures, particularly in the ’70s films that remain among his best; but he could use his appeal to equal and devastating effect in romance, notably opposite Barbra Streisand in The Way We Were (1973).

Behind the California-kid surface was a darker and more complicated figure. The very definition of a Hollywood star, he nonetheless saw himself as an outsider and spent much of his time living away from the epicenters of the industry — including at the Utah skiing resort that he turned into the Sundance Institute and the Sundance Film Festival.

He bestrode two worlds, his biographer, Michael Feeney Callan, wrote in 2011: “His life [was] peripatetic. He engaged [in] careers on the East Coast and West. It may not be a coincidence that his arts laboratory — his ‘great experiment’ [Sundance] is not too many miles from Promontory Summit, where, in 1869, the golden spike was hammered that joined the East Coast and West on the transcontinental railroad.”

Born in Santa Monica on Aug. 18, 1936, Charles Robert Redford Jr. grew up poor in a heavily immigrant part of town, his family scraping by on the earnings of his father, a risk-averse milkman who later became an accountant. “[He] worked brutal hours,” Redford, an only child, remembered in a 2014 interview with THR. “I didn’t see much of him when I was a kid.”

His mother, Martha, a homemaker, “was the strong member of the family. She was very outgoing. She always had a smile; she was very, very adventurous. Risk was not a big issue for her. She came from Texas, and she carried that kind of robust, jocular goodwill. She saw things in a positive light. She also felt that I could do anything, and she was very supportive of anything I might try.”

Redford rebelled against his father’s cautiousness and indeed against all expectations, even after the family moved to the more upscale Van Nuys. “I was always about breaking the rules,” he said. “I wanted to be away from Los Angeles because I felt it was going to the dogs. I was just getting more and more anxious about wanting out. I didn’t want to be wherever I was. And I felt a certain suffocation. I felt things were closing in around me, and it made me anxious. I wanted to be free.”

His dream was to follow in the footsteps of the great artists who had made Paris their hub; he didn’t consider a career as an actor until later, after dropping out of the University of Colorado following his mother’s death in 1955, when he took months off to travel around Europe. He was deeply affected by his experiences in Spain, Italy and France. “It was the first time I developed any kind of a political view,” he said, “because I couldn’t care less about politics when I was growing up.”

He became a passionate environmentalist and supporter of Native American and LGBTQ rights and remained that way throughout his life. In 2018, he published on the Sundance website a lament about the state of America titled, “A Brief Statement About Big Things.”

“Tonight,” he complained, following the news of Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court, “for the first time I can remember, I feel out of place in the country I was born into and the citizenship I’ve loved my whole life.”

After returning to the U.S., he studied at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts and then found work in theater and television. He became a young father and had four children with his first wife, Lola Van Wagenen, whom he had met when she was a 17-year-old student at Brigham Young University. One son, Scott, died at 2 1/2 months old from sudden infant death syndrome in 1959, leaving Redford guilt-ridden even though there was nothing he could have done, and his other son, Jamie, died in October 2020 of bile-duct cancer in his liver.

He is survived by his daughters, Shauna and Amy; his second wife, Sibylle Szaggars, whom he married in 2009; and seven grandchildren.

He made his onscreen debut in a 1960 episode of ABC’s Maverick. Three years later, he earned an Emmy nomination for his work on an installment of the ABC anthology series Alcoa Premiere and starred in a memorable Broadway production of Neil Simon‘s Barefoot in the Park (directed by Mike Nichols), which he later filmed alongside frequent collaborator Jane Fonda.

“You feel that he is somehow better than most other mortals,” she wrote in her 2005 autobiography, My Life So Far. “You want Bob to like you, so you are loath to do or say anything that might make him think less of you.”

After the play, Redford turned down a number of high-profile roles, including the lead in Nichols’ The Graduate (1967). “I was suddenly Mr. Focus,” he told Callan. “Eleanor Roosevelt and Noël Coward dropped by. Natalie Wood came backstage. Bette Davis summoned me to her suite at the Plaza.” Ingrid Bergman gave him advice he took to heart: “Do only good work.”

Redford’s early movies also included his debut, Tall Story (1960), and Inside Daisy Clover (1965), which won him a Golden Globe as best new star. He was a star, but not a superstar. That changed in 1969 when he appeared as the Sundance Kid opposite Paul Newman, taking a role that had been offered to Jack Lemmon, Warren Beatty and Steve McQueen.

“The studio didn’t want me,” he recalled. “It all depended on Paul, and I met him and he was very generous and said, ‘Let’s go for this.’ He knew I was serious about the craft. That’s what brought us together, and we became friends, and our friendship turned out to be very similar to our relationship in both Butch Cassidy and The Sting” — the 1972 follow-up to Butch Cassidy that won the Oscar for best picture.

Many critics dismissed Butch Cassidy. Pauline Kael in The New Yorker called it “the bottom of the pit” (prompting a furious letter from director George Roy Hill, which began: “Listen, you fucking c—t”). But the picture was a massive hit and has come to be seen as a classic.

Robert Redford and Paul Newman in 1969’s ‘Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.’

Courtesy of 20th Century Fox Film Corp./ Courtesy Everett Collection

“The effects of Butch Cassidy were far-reaching for Redford,” wrote Callan. “In February 1968, [Redford had] been sleeping in hotel hallways in Grenoble … to save money. Two years later, in February 1970, he was a national icon on the cover of Life magazine.”

He followed Butch Cassidy with Downhill Racer (1969), Jeremiah Johnson (1970) and The Candidate, about a U.S. Senate contender who is the perfect front man but then seems lost when he faces the prospect of governing. “What do we do now?” he asks in the movie’s famous last line. Years later, Redford toyed with making a sequel, to be written by Larry Gelbart. “The truth is so awful,” he told Maureen Dowd of The New York Times in 2003, “but in its own horrible way, it’s entertaining.”

With Downhill Racer, he became a producer and through his Wildwood Enterprises developed All the President’s Men, based on the Watergate book by Woodward and Carl Bernstein. (Curiously, Redford had met President Nixon as a teenager and said he got “a creepy vibe” from him.)

He had met Woodward and Bernstein in Washington before their book was finished and paid $450,000 for the film rights, then was disappointed in William Goldman‘s script, which he heavily rewrote with director Alan J. Pakula after turning down Bernstein and Nora Ephron’s adaptation.

The drama, also starring Dustin Hoffman as Bernstein, was a monument to dramatic realism, so serious in its attempt to capture the truth that the production took bags of trash from the real-life Post offices and used the papers on the set. Pakula shot an astounding 300,000 feet of film, which was reduced to 12,300 in the final, 2-hour, 18-minute movie.

Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford in 1976’s ‘All the President’s Men.’

Courtesy Everett Collection

The film almost had a different ending: “Pakula,” notes Callan, “wanted to show TV footage of Nixon’s resignation and the famous defiant farewell wave on the steps of the helicopter on the White House lawn.” Redford resisted. “I told Alan again and again, ‘This isn’t about Nixon. It’s about journalism.’” They compromised by showing a teletype machine ticking away, announcing Nixon’s decision.

Four years after President’s Men, Redford tried his hand at directing with Ordinary People (1980), based on Judith Guest’s novel and adapted by Alvin Sargent. It was an intimate family drama that Pakula regarded as subliminal autobiography. “When I read it,” he noted, “I said, ‘Oh, I get it.’ The novel is about parental tyranny … Bob is moving some furniture here. He is co-opting the novel’s dysfunctional family for his father’s or his own and investigating himself at a critical time.” Redford denied that.

The finished picture, wrote critic David Thomson, “came as an impressive surprise to the public and the Academy. It was observant, heartfelt and full of anguished performances. And it was appreciated that Redford was concentrating on the script and the actors and directing with stylistic restraint and professional anonymity. The surprise now may be that Ordinary People won best picture and the Oscar for best director when Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull was among its rivals.”

Redford’s other films as a director included The Milagro Beanfield War (1988), A River Runs Through It (1992), Quiz Show (1984) — for which he received another Oscar nom — The Horse Whisperer (1998), The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000) and The Conspirator (2010).

None of his later movies as an actor equaled those of the late ’60s and ’70s, even though many were hits. They included The Natural (1984), Out of Africa (1985) — another Academy Award best picture — and Indecent Proposal (1993). In all, Redford’s naturalism was so convincing, his acting so skilled, it almost disguised his talent; he never won an acting Oscar.

Producer Sherry Lansing remembered how he took Indecent Proposal‘s most memorable moment — when his character, billionaire John Gage, offers a young man $1 million to sleep with his wife — and tossed it off with brilliant casualness, as if throwing the line away. This was a man for whom there was not much difference between $1 and $1 million, any more than there was any difference between lust and love. Everything about him was revealed in that line — not least the actor’s intelligence in choosing not to play it melodramatically.

Lansing also saw a more sensitive side to Redford than he revealed to those who didn’t know him well. After a stupendous table reading just before the shoot, in which the actor blew everyone, including co-stars Woody Harrelson and Demi Moore, away, Lansing was summoned to see the star. “I thought he was going to tell us he didn’t like something in the script,” she recalled. “But he said, ‘I want out. The kids are wonderful. But I’m not. It’s their movie.’ ” He was so insecure about his performance, he was ready to leave the film. Only the deft intervention of his CAA agents kept him onboard.

He was a perfectionist who was as critical as himself as of others. “I was born with a hard eye,” he told THR. “The way I saw things, I would see what was wrong. I could see what could be better. I developed kind of a dark view of life, looking at my own country. When I was a kid, I was told to be a good sport. It wasn’t whether you won or lost; it was how you played the game. I realized that was a lie.”

He was notoriously unpunctual and often took months or even years to commit to a project, only to insist on changes and then sometimes pull out. He avoided darker, more dissolute characters, even though he was also drawn to them. Dan Melnick, the late Hollywood executive and producer, cautioned 20th Century Fox that Redford would never agree to play the alcoholic lawyer in The Verdict (1982) no matter how much he insisted he would. Melnick was right; Redford dilly-dallied until he was fired by producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown and replaced by Newman.

Redford’s later films included Spy Game (2001) and the Marvel superhero movies Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014) and Avengers: Endgame (2019). Despite his advocacy for indie film, he preferred studio movies and only later embraced independent vehicles such as All Is Lost (2013) and A Walk in the Woods (2015).

He kept working steadily, even relentlessly, playing news anchor Dan Rather in Truth (2015) and a widower who falls for his neighbor (Fonda) in Our Souls at Night (2017), all the while maintaining his involvement with Sundance; indeed, he only stepped down as the public face of that organization in 2019. That was almost two decades after the Academy had awarded him an honorary Oscar and slightly more than two years after President Obama had given him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. His final onscreen appearance came this year in an uncredited cameo on the AMC series Dark Winds, on which he was an executive producer.

Redford announced his retirement from acting just before the release of The Old Man and the Gun (2018). By then, Thomson argued, he had “lost the intriguing edginess he had in the ’70s. He’s not the only member of his generation to shift from sunlight to sunset.”

If he had lost some of his edge, he had not lost his perfectionism. “When I started to direct, I wanted total control of the story,” he told THR. “I didn’t want to be dependent on anyone. But then you add producing to that, and then you add Sundance, and pretty soon you’re adding all these layers. Was all that other stuff worth it? That’s an open question.”

Stephen Galloway is dean of the Chapman University film school.

THR Newsletters

Sign up for THR news straight to your inbox every day

Robert Redford

“A Genius Has Passed”: Tributes Pour in for Robert Redford After His Death

Oscars: Iran Picks ‘Cause of Death: Unknown’ as Best International Feature Submission

Toronto International Film Festival 2025

Has TIFF Got Its Groove Back?

Toronto Film Festival

‘Glenrothan’ Review: Brian Cox’s Scotland-Set Directorial Debut Combats Sibling-Drama Clichés With Good Acting

Toronto International Film Festival

‘Normal’ Review: Bob Odenkirk Fires on All Cylinders in Ben Wheatley’s Jaw-Droppingly Excessive Blast of a Crime Caper

Paula Shaw, Actress in ‘Freddy vs. Jason’ and Hallmark Holiday Telefilms, Dies at 84

The Hollywood Reporter is a part of Penske Media Corporation. © 2025 The Hollywood Reporter, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER is a registered trademark of The Hollywood Reporter, LLC.

Powered by WordPress.com VIP