Two government parties, the Finns Party and the Swedish People’s Party, have expressed interest in adopting Canada’s points-based system to assess applicants for work-related residence permits.

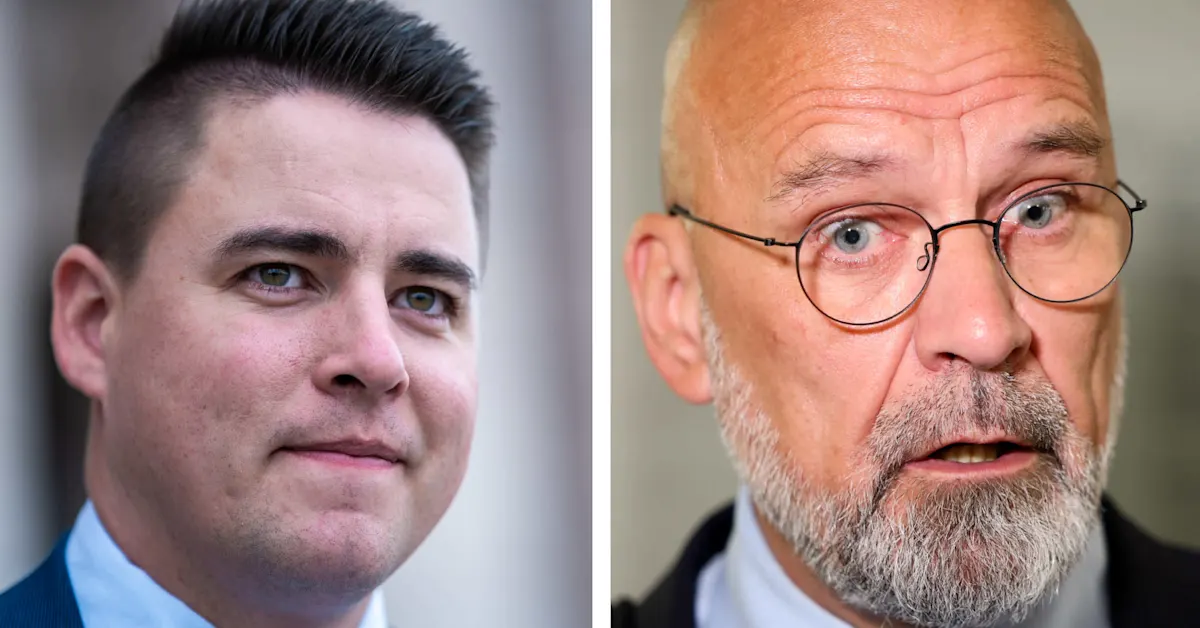

“The advantage of Canada’s model is that it sets clear targets for how many labour migrants are needed by region, language group and sector,” said Christoffer Ingo, an MP for the SPP.

According to Ingo, the system also benefits migrants themselves, since it defines what is required of those wanting to move to Finland.

Canada awards points for factors thought to ease integration. Young, educated and linguistically skilled applicants with regional ties score highly, improving their chances of securing residence permits.

“But we should not be picky to the point of demanding excessively high scores. Our economy needs skills, even if not all other criteria are met,” Ingo added.

Is this a way to attract more people to Finland, or a means of keeping out those deemed unwelcome?

“For the Swedish People’s Party, the aim is clearly to increase work-based immigration. But it’s hardly a drawback if people who arrive also have better prospects of integrating.”

Would points simplify the current system, or add another layer of bureaucracy?

“In Canada, the system is highly flexible and frequently updated. We know the labour market can change quickly, so any model we adopt must be able to change accordingly,” he said.

Ingo argued that a points system could replace labour-market testing, the current method used to restrict labour immigration when suitable workers are already available in Finland.

Do you see any downsides to evaluating people according to a points system?

“When it comes to labour, there is already a hiring process, which is in a way a form of scoring, so I don’t necessarily see it as a problem. But I want to be clear that this should not apply to humanitarian immigration. There, people should not be scored — we should help those in need,” he explained.

The Finns Party, meanwhile, wants to introduce a points system for all forms of immigration.

Mauri Peltokangas, a Finns Party MP and chair of Parliament’s Administration Committee, is also a fan of Canada’s rating system.

“This way, we can attract people to Finland who have great potential to support the economy,” Peltokangas noted.

He said he believes Canada has also succeeded with its points criteria. In Finland, skills in English or French, he suggested, could simply be replaced with Finnish or Swedish.

“If you compare someone without education and language skills to a graduate who has already studied Finnish or Swedish, it’s not hard to guess who’ll need support and who can manage on their own,” he said.

Should this apply only to labour immigration, or do you think the model could also cover humanitarian residence permits?

“There is nothing wrong with applying points to humanitarian immigrants as well. There are a billion people in the world who need help. If Finland accepts a small fraction of them, I think it makes sense to prioritise those who are likely to adapt more easily to our society.”

Work-based immigration to Finland has declined as long-term unemployment has approached record highs. Last year, the number of first residence permits issued for employment fell 23 percent, compared to figures in 2023.