By Assel Satubaldina,Fatima Kemelova

Copyright astanatimes

ASTANA – The Caspian Sea, the world’s largest inland body of water, is shrinking. Scientists warn that water levels could fall by as much as 21 meters by 2100, threatening biodiversity and the livelihoods of nearly 15 million people living along the coast.

The Caspian Sea is shared by five countries of Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan. It covers an area of nearly 387,000 square kilometers. The Caspian Sea receives water from around 130 rivers, with the Volga River accounting for 86.1% of the Caspian’s total river inflow.

The Caspian Sea is also part of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, also known as the Middle Corridor, the fastest route from China to Europe, and a major source of oil and gas.

However, the Caspian Sea faces an ecological emergency. This is what President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev pointed to as a “very delicate yet serious issue.”

“The situation is approaching an environmental catastrophe,” said Tokayev as he addressed the SCO Plus meeting in Tianjin on Sept. 5.

Cycles of decline and rise in water levels.

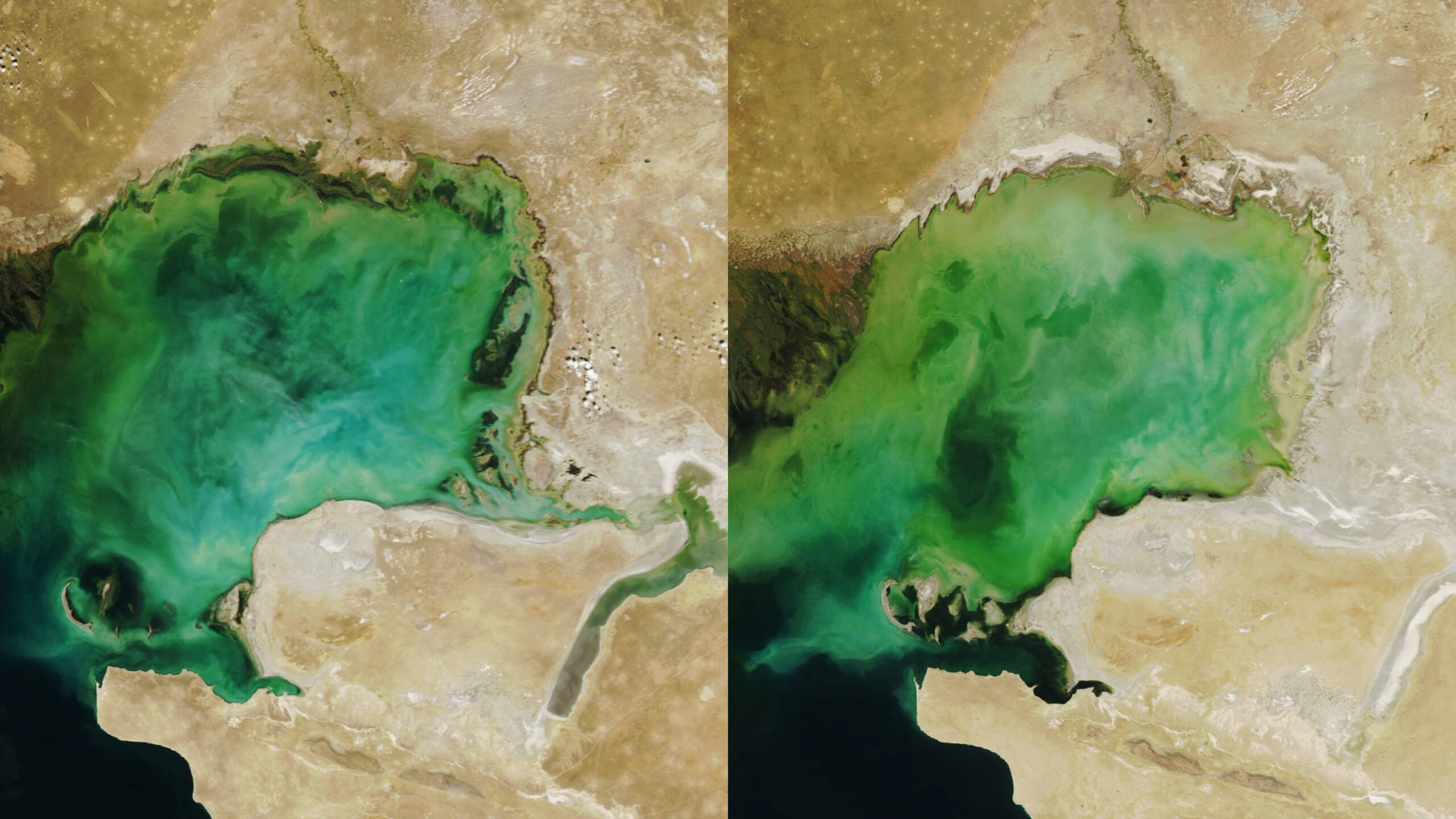

According to experts from the Central Asia Climate Fund (CACF), throughout the history of observations, the Caspian Sea has gone through several cycles of decline and rise in water levels. In less than 20 years, the surface area of the Caspian Sea has shrunk by more than 34,000 square kilometers.

Between 1940–1977, the sea level fell by an average of four centimetres per year, a total drop of 1.2 meters. From 1978 to 1995, the level rose by 13 centimetres annually, adding 2.5 meters overall, and between 1996 and 2023, the sea again declined, losing eight centimetres per year, or 1.83 meters in total.

This trend is observed today. From 2006 to 2024, the sea level dropped by 2.14 meters.

“NASA satellite data from 2020–2025 show that the Caspian Sea level is dropping at a rate of nearly seven centimeters per year, 20 times faster than the rise of the global ocean. If the trend continues, the northern part of the sea, where depths do not exceed five meters, could virtually disappear by 2050,” writes the fund in its August report.

Alarming situation

Speaking to The Astana Times, Mirgaliy Baimukanov, director of the Almaty-based Institute of Hydrobiology and Ecology, described the ecological state of the Caspian Sea as “extremely strained and alarming.”

“Decades of pollution from industrial and agricultural waste, the spread of invasive species, unregulated fishing, and widespread poaching of bioresources have created conditions where the sea’s native inhabitants are, quite literally, struggling to survive,” Baimukanov said.

“The Caspian Sea is a closed body of water. Its drainage basin is ten times larger than its surface area, collecting inflows from 130 rivers, yet it has no outlet. As a result, all harmful substances accumulate in the sea and on its seabed. This process is only intensifying,” he added.

The sea’s ecosystem suffers significantly from the ongoing decline in its water level.

“Warming and the reduced flow of rivers are the primary causes of this decline, which brings both economic losses and severe ecological uncertainty. According to existing forecasts, the entire northern Caspian is expected to dry up by the end of this century. Salt storms and the desertification of vast areas are among the most visible consequences for the northern Caspian region,” Baimukanov said.

Mounting risks for biodiversity

The Caspian Sea is home to more than 300 endemic invertebrates, 76 fish species, and the Caspian seal, found nowhere else on Earth. Its coastal wetlands also host globally significant populations of waterfowl and migratory birds, lying at the crossroads of major flyways that link Europe, Asia, and southern Africa.

Baimukanov pointed to the Caspian seal as one of the key indicator species whose condition offers critical insight into the overall health of the sea’s ecosystem.

“The Caspian seal sits at the very top of the sea’s food chain. It is a species that feeds mainly on fish, but also on mollusks and crustaceans. It migrates across the entire basin. It is an endemic species that has lived in the Caspian for hundreds of thousands, possibly up to two million years. Therefore, the seal serves as an indicator species of the sea’s ecological health,” Baimukanov said.

Unregulated, excessive fishing led to the decline in the population of seals.

“In the first third of the last century, annual catches reached as many as 230,000, averaging around 115,000 a year. By the mid-century, the volume of hunting had dropped to just a few tens of thousands, and later the hunt was halted altogether due to economic inefficiency,” he said.

The industrial revolution that spread rapidly in the 20th century polluted the sea with oil products, heavy metals, and toxic chemicals.

“Toxic substances at levels many times higher than the permissible limits have been found in the organs and tissues of Caspian seals. This has led to increased infertility among mature females and, consequently, a decline in reproduction. The buildup of toxins also weakens the animals’ immune systems, making them more susceptible to disease. The direct outcome of these processes was the mass die-off of seals, repeatedly observed in the late 20th and early 21st centuries,” Baimukanov explained.

The Caspian seal is classified as an endangered species on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List, a status recognized in the legislation of all Caspian littoral states.

While Caspian seals adapted to amplitude fluctuations in sea level, Baimukanov acknowledges there is one thing they have yet to cope with.

“The Caspian seal must adapt to the destruction of its habitat as a result of human activity. This is a semi-aquatic animal; it spends much of its life on ice and land. In winter, seals gather on the ice of the northern Caspian to give birth, nurse their pups, and mate. In spring, they move to shallow-water islands to molt, while in autumn, they return to the islands to await the formation of ice cover,” he said.

According to Baimukanov, industrial operations on the northern Caspian shelf depend on icebreakers to reach offshore oil fields in winter. As the sea recedes, navigation channels must be continually dredged to maintain access.

“This makes it essential to conduct oil operations with great care and in full compliance with all requirements, so as not to scare the seals away or destroy their already fragile habitats. After all, only in Kazakhstan’s sector do suitable conditions for this unique species still remain,” he said.

Ongoing research into the Caspian seal

Baimukanov said the institute carries out comprehensive research to assess the conditions of habitat, population and distribution of Caspian seals.

“Research pays close attention to monitoring mortality as well as the size, age, and sex composition of dead seals. Determining the cause of death is often difficult unless there are obvious signs, such as bruises, decapitation, or other injuries from ship propellers, or cuts on the neck from fishing nets or poachers’ knives,” he said.

Seals also die from marine pollution and diseases caused by viral and bacterial infections.

Baimukanov noted that the Caspian Sea was reported to contain micro and macroplastics, which accumulate toxic elements. Fish consume the very same plastic before it travels up the food chain, ultimately threatening the Caspian seal at its apex.

“Each spring and autumn, when almost the entire population gathers in the northern Caspian, hundreds, sometimes even thousands, of carcasses are washed ashore. They appear in varying stages of decomposition, but most are too advanced to identify the cause of death. While some seals die of natural causes, many of the victims are not old, and in recent years, there has been a rise in the deaths of pregnant females. This all points to an increasingly unhealthy habitat,” Baimukanov explained.

Researchers use satellite imagery to search for new islands and sandbanks that may serve as haul-out sites for seals.

“Routes are charted, and we reach them by boat. We check each site, mapping and photographing them, collecting water and soil samples, and assessing food availability near the rookeries. Seal feces are also gathered and analyzed to better understand what the animals are eating,” Baimukanov said.

When staying longer, they are also observing the behaviour of seals in an effort to understand aspects of their biology that remain unknown.

“We still do not understand how parent pairs are formed, what sense or instinct guides them in choosing one another, how long they remain ‘in love,’ or what they feel when they lose a mate or a newborn pup. Yet we notice how their large, dark eyes look at us with sorrow and reproach whenever we intrude into their lives,” he said, adding that they are looking for methods that would disturb the seals as little as possible.

The time spent close to these animals makes Baimukanov understand better why they should be protected from humans.

“There is still so much we do not know about the seals, so clumsy on land, yet so graceful and curious in the water. And one wonders: who is more eager to learn – we about them, or they about us? Only on those lonely islands, listening to their low, mournful rumble at sunset, do you realize how deeply we are obliged to protect them from ourselves,” he said.

Regional cooperation mechanisms

Baimukanov noted an extensive legislative base for regional cooperation formed in the past two decades, including the Framework Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Caspian Sea, also known as the Tehran Convention, and the Agreement on the Conservation and Rational Use of Aquatic Biological Resources of the Caspian Sea. Both documents have been ratified by all five littoral states.

“In 2024, on the initiative of President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, Kazakhstan established the Caspian Seal State Nature Reserve, the first specialized reserve among Caspian littoral states dedicated to protecting the species. Its creation underscores the country’s deep concern and responsibility for safeguarding this unique animal and the wider Caspian ecosystem,” he said.

However, one country’s actions are not enough.

“As the sea continues to regress and its shoreline shifts, shrinking like a piece of shagreen leather. Kazakhstan’s territorial waters no longer cover the main seal rookeries. This creates an urgent need for a joint transboundary reserve among all Caspian states. Experts recommend establishing a network of specially protected natural areas that would coordinate biodiversity monitoring across key ecosystems, actively cooperate, exchange data, and implement conservation measures together,” he said.

Researchers believe some declines in the level of the Caspian Sea are unavoidable, even if actions to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions are in place.

“However, with the anticipated effects unfolding over a few decades, it should be possible to find ways to protect biodiversity while safeguarding human interests and wellbeing. That might sound like a long timescale, but, given the immense political, legislative and logistical challenges involved, it is advisable to start action as soon as possible to give the best chance of success,” said Dr Simon Goodman from the School of Biology at the University of Leeds.