Unlike many people she grew up with, Sarah Barron lives in Howard County, where she was born and raised.

She initially moved away from the county of fewer than 10,000 people in Northeastern Iowa after graduating high school, eventually ending up in Fort Collins, Colorado, where she met her husband, Emmanuel, and had three sons.

Wanting to escape city life and raise their kids in the country, Sarah and Emmanuel, both in their 30s, moved back to her hometown of Lime Springs in 2023 to be closer to her grandmother.

“I wanted to be in the country, I wanted to raise my kids like how I grew up,” Sarah said. “We were in the city, a little, teeny backyard. Now I’m like, ‘Go outside and play.’ And they’re like, ‘By ourselves?’ ”

Sarah, a second-grade teacher at her kids’ school in Riceville, and Emmanuel, an archeologist in the nearby town of Cresco, like living in rural Iowa, where it’s quiet and affordable. Their children can grow up the way they did by playing outside in their vast backyard until dinnertime.

While she was away, Sarah didn’t expect things to change much in Howard County. But in 2016, the county garnered national attention for one key reason: its colossal political shift.

Out of Iowa’s 99 counties, Howard had the largest move rightward in the last 12 years, swinging 52.45 points toward Republicans in presidential elections. It’s a county that former President Barack Obama won twice and that went to President Donald Trump by over 20 points in the last three elections. 2016 was the first time the county went to a Republican since former President Ronald Reagan in 1984.

And nationally, it saw the second-largest flip from Obama to Trump in the country.

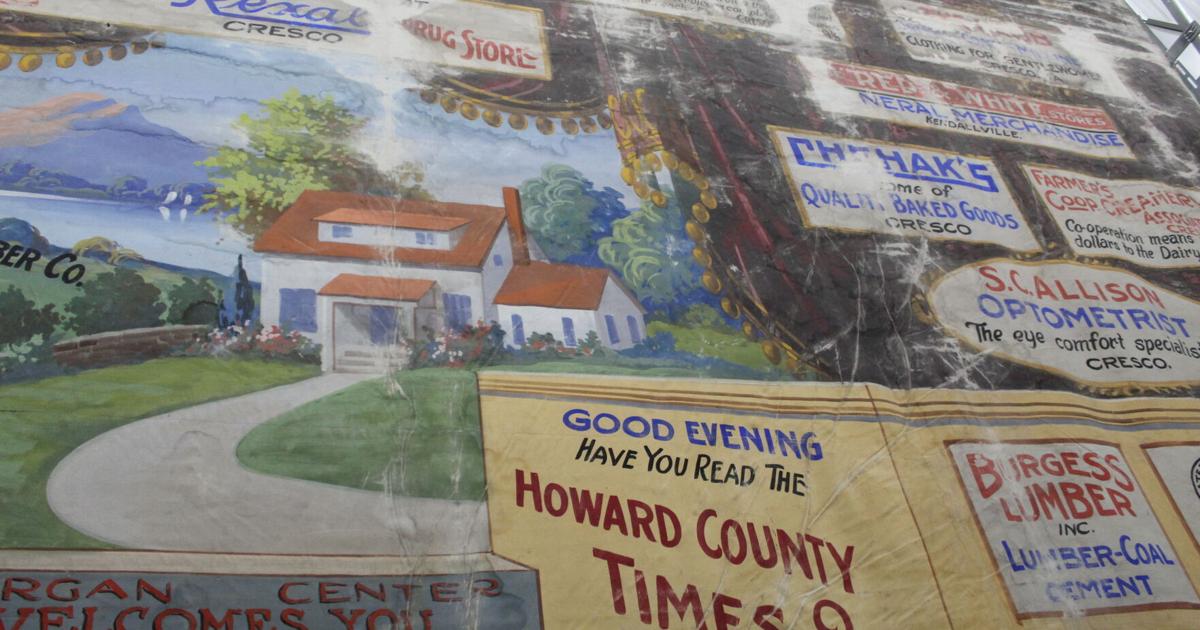

After the 2016 election, national media flocked to the area, talking to locals and attempting to dissect Howard County and figure out why it, like many other rural counties across the country, took a sharp turn away from Democrats and toward Trump.

Agriculture, manufacturing main industries

Howard County, which hugs Minnesota’s southern border, has just over 9,000 residents. The county is 94% non-Hispanic white, compared with the state-wide average of roughly 83%. Just 19% of residents hold bachelor’s degrees, which is just over half of Iowa’s 31.5% degree attainment average. And the average annual household income is $67,336, below Iowa’s $71,433.

The county is the birthplace of Norman Borlaug, who in 1970 won the Nobel Prize for his efforts to increase crop yields which helped feed the world.

Like most rural counties in Iowa, Howard’s population has declined while the state has grown. From 2010 to 2024, the county’s population decreased by 2.18% from 9,569 to 9,360, while Iowa’s population increased by about 6.2% in the same time period.

But Howard’s County population is stable compared to other rural counties in Iowa, and, while some other small towns see factory closures, industry remains relatively strong in the area.

Agriculture and manufacturing are the county’s main industries, driven by companies including Upper Iowa Beef, Alumaline, Donalson and Featherlite, which makes lightweight trailers commonly used by NASCAR.

Many feel left behind by political parties

Still, many of the county’s residents feel like the area was left behind by both national political parties, as lifelong residents have watched mom and pop shops close and younger people leave the area.

Barbara Prochaska, a member of the Howard County Historical Society, moved to Cresco in the 1950s and worked in real estate in the area for the past few decades. She said a lot of people who work in town and other industries in the county drive in from other areas.

“We are quite short on rental properties and affordable housing for young families,” Prochaska said.

Mike Gooder, the owner of a plant and flower company, Plantpeddler, in Cresco, said the biggest barrier to filling the jobs is a lack of affordable housing, especially for younger families and workers.

Gooder, a fifth-generation local of the county, and his wife worked at the company in high school before taking over in 1980. He said the company plans to open a larger retail location in Cresco in November to help ensure local businesses can regain prominence in the area after many have shuttered over the years, including the town’s only car dealership.

“It’s a classic chicken and egg scenario of you’ve got to have the housing to get the people, to have the industry, to have the support of the jobs. It’s all married together and really very interlinked when you look at the complexity of having rural communities be strong and healthy,” Gooder said. “Part of the reason we’re reinvesting in retail is we know that if you start losing retailers in a community, the community will die,”

Gooder, who voted for Trump in the past three elections, is a registered Republican, but has voted for Democrats in the past. He didn’t initially support the president when he first ran for office in 2016 and is still split on his actions during the first eight months of his second term.

He agrees with Trump’s energy policies because his company is heavily reliant on natural gas, and he feels it’s cheaper when Trump is in office. On the other hand, he is wary of the president’s stance on immigration and doesn’t agree with many of the recent deportations across the country.

“Everybody deserves at least some shot at that opportunity as long as there’s a legal pathway, and I think we need to work hard at it,” Gooder said. “If you come in the country there should be a pathway that you keep your nose clean, you work hard, you pay taxes, you do all things that a model citizen can.”

Gooder, like many people he grew up with in the area, was raised in a “Kennedy Democrat” household. And Gooder says they felt they had been left behind by the national Democratic Party, including on agricultural issues.

“You saw a lot of farmers that had traditionally voted Democratic because of farm policy … make a switch and voted Republican, it just seems that element is strong,” Gooder said. “The party left the average Democrat. I think that’s a lot of people who became disenchanted with some of the policy.”

Kedron Bardwell, a professor of political science at Simpson College, has spent a lot of time researching Iowa’s political shift. Through his work, he’s heard from many Iowans who believe the national Democratic party lost touch with rural voters.

“The Democratic Party is perceived now as the party of the elites,” Bardwell said. “Whether that’s the education level thing, college-educated level thing … Hollywood elites, it might mean not in touch with average rural or small-town voters anymore.”

Democrats lose footing in the county

Like Gooder, Sarah Barron was raised in a Democratic household. She describes her grandma as a “hardcore Democrat.”

Sitting at a picnic table on Lime Springs’ main drag during Sweet Corn Days, a three-day long event full of community activities, a parade, music and free sweet corn, Sarah spoke about her political upbringing while she and her three sons picked at a fresh funnel cake.

Sarah caucused for Obama in 2008, where she remembers seeing significant turnout.

In 2016, Sarah was a fan of then-presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and said she knew a lot of other younger people in the area who backed him. She was disappointed when Hillary Clinton eventually became the Democratic nominee and felt like that’s where the party started to lose younger voters.

“Hillary and Biden, that was where it all went wrong for the younger folks,” Sarah said.

Clinton narrowly beat Sanders in 2016 by less than half a percentage point in the Iowa Democratic caucuses.

In 2024, Sarah and her husband, Emmanuel, reluctantly voted for then Democratic presidential nominee and former Vice President Kamala Harris over Trump.

“Our vote for Kamala wasn’t ideal,” Emmanuel said. “We thought she was a crappy candidate. What really bugged me personally was … not having a vote, after Biden dropped out, for a candidate. That did not jive well with me personally.”

‘They shoved him (Biden) down our throats’

Sarah said the party’s choice of Biden as a candidate in the last two elections felt similar to the party choosing Hillary for the Democratic nominee over Bernie in 2016.

“They shoved him (Biden) down our throat,” Sarah said.

While 2016 was when Sarah’s enthusiasm for the Democratic party began to fade, it’s also when Howard County Democrats Chair Joe Kaletka took an interest in politics. During his time in political organizing in the area, Kaletka has taken notice of the national Democratic Party’s tainted reputation in the county.

When knocking doors last election, party members instead drew focus to the Democratic candidate for Iowa’s 2nd Congressional District, Sarah Corkery, over Harris at the top of the ticket.

“When you mention a candidate in a race that they haven’t really tuned into, then you have a little bit more pleasant conversations of talking about candidates that aren’t so nationally talked about. I think everybody gets so burnt out about talking about the same people year after year,” Kaletka said.

Kaletka, 24, was born and raised in Cresco. He recently took over as leader of the county party after longtime chair, Laura Hubka, stepped down from the role. As one of the youngest Democratic county party chairs in the state, he jokes with his friends and family about the age gap and gender difference between him and other members of the party.

“All of my friends and my parents always joke that whenever I’m doing something political, it’s me and my old lady friends,” Kaletka said with a smile. “I’m not complaining at all, because they certainly keep me in line.”

Speaking on his own behalf, Kaletka said he feels that the county party, similar to surrounding rural Democratic parties, has been left behind by both state and national Democrats. Instead, the county party has started collaborating with nearby counties on voter mobilization, including Mitchell County to the west.

“Showing up, being visible, being here, being willing to listen, stuff like that, goes a long way,” Kaletka said. “A lot of rural counties feel left behind by the state party. So we kind of pick up our bootstraps and just work together amongst ourselves. And the state doesn’t give us any direction. We just kind of go, ‘OK, let’s do this.’”

‘The middle is left kind of wide open’

Although it votes heavily for Republicans, many of Howard County’s voters aren’t registered with a specific political party. As of September, the county had 1,808 active registered Republicans, 1,188 active registered Democrats and 2,254 active registered independents.

Neil Schaffer, chair of the Howard County Republican Party, says a lot of residents in the county lean more on the independent side and said the swing to Trump makes sense based on what he says is fatigue from the traditional political parties.

“We definitely are not party-driven, we’re individually driven,” Schaffer said. “Not unlike a lot of rural areas, getting away from the traditional party that really never excited anyone too much. You know, we kind of held our nose and voted for McCain and … held our nose and voted for Romney.”

Schaffer, 58, lives west of Cresco on the farm where he grew up. He said a lot of Howard County residents gravitated toward Trump because they viewed him as a different option from the status quo.

“People realized that it didn’t really matter what party was in the White House or in Congress, it seemed like the same things were happening,” Schaffer said. “Debts continued to rise and spending continued to be out of control, and we continued to get into wars, and then Donald Trump came along.”

Gooder also knows a voting block in the county where voters keep their cards close to their chest and tend to switch back and forth between candidates.

“The middle is kind of left wide open. We have a far-right policy in politics and a far-left policy and those people in the middle are like, I think a little bit lost. Which party fits them?” Gooder said. “You also look at the people that prefer to be on the sidelines until you get to the election. So they’re not going to attend a rally. They’re not going to be involved. They get inside of the voting booth and they make that decision.”

With the 2026 midterms on the horizon, where Iowans will have a chance to vote in an election where the governor’s and a U.S. Senate seat are open, Gooder says he thinks it’s any party’s game depending on how they can break through to voters in rural Iowa.

“The pendulum will swing back,” Gooder said. “The pendulum always seems to swing in Iowa.”

Love

0

Funny

0

Wow

0

Sad

0

Angry

0

Get Government & Politics updates in your inbox!

Stay up-to-date on the latest in local and national government and political topics with our newsletter.

* I understand and agree that registration on or use of this site constitutes agreement to its user agreement and privacy policy.

Maya Marchel Hoff

Statehouse Reporter

Get email notifications on {{subject}} daily!

Your notification has been saved.

There was a problem saving your notification.

{{description}}

Email notifications are only sent once a day, and only if there are new matching items.

Followed notifications

Please log in to use this feature

Log In

Don’t have an account? Sign Up Today

Sarah Watson

Davenport, Scott County, local politics

Get email notifications on {{subject}} daily!

Your notification has been saved.

There was a problem saving your notification.

{{description}}

Email notifications are only sent once a day, and only if there are new matching items.

Followed notifications

Please log in to use this feature

Log In

Don’t have an account? Sign Up Today