“Making Sausage: from Illinois farm to a 45-year career in public service in Alaska”

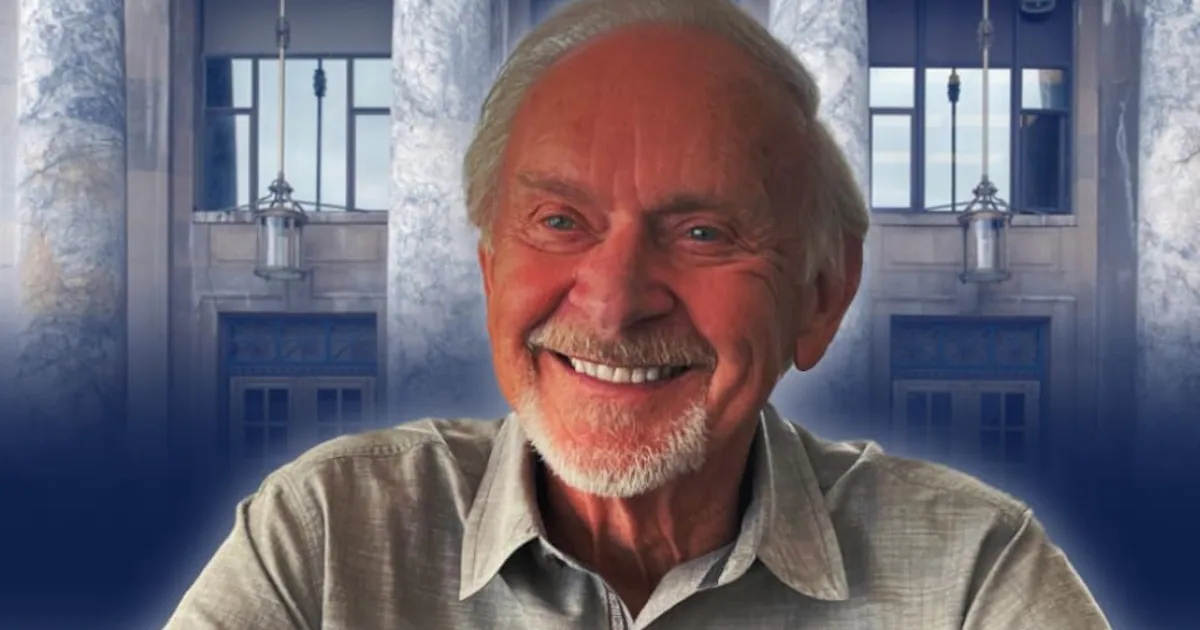

By Jim Duncan, 2024; 349 pages; $20.

Most people have probably heard the saying that watching laws being made is like watching sausage-making. It’s best not to observe the messy process or to know what goes into the final product. Longtime Alaska politician Jim Duncan chose an apt title to describe his decades-long career in public service.

Alaskans will likely know Duncan, who today lives in Anchorage, as a Democratic member of the Alaska Legislature from 1975 to 1998, representing Juneau. Prior to that he served as an educator and Juneau assembly member. He later served as Alaska’s Commissioner of Administration under Gov. Tony Knowles and, for 15 years, as the executive director of Alaska’s largest public employees union.

“Making Sausages” examines in full view the sometimes unsavory process of crafting and negotiating public policy while also demonstrating the value of serving the needs of Alaskans. As Duncan writes, his memoir is meant as a history of issues important to the development of Alaska. That history, and those issues, are not behind us. Education funding, oil taxation, the Permanent Fund and the Permanent Fund dividend, the need for a long-term fiscal plan, and various social issues are still debated every year. His drive to write the book came from his concern that policy-makers today don’t know the background to the issues they’re attempting to address. Alaskans, so many of whom are new arrivals, have even less understanding of what has shaped our present policy and budget discussions.

Duncan gives considerable attention to the 1981 legislative session, when he served as House Speaker until overthrown in what was called a “coup.” Toward the end of the session, the Democratic majority was replaced by a coalition of Republicans and rural Democrats. The popular explanation was that rural representatives had felt they deserved larger shares of the budget and that others were dissatisfied with the way the session was proceeding. In his chapters “The Hidden Agenda” and “The Oil Tax Coup” Duncan makes a compelling case that oil taxation was the larger controlling issue. The Republican leadership after the coup changed oil tax policy to favor the oil industry. Later analyses showed that the change cost the state hundreds of millions of dollars.

Throughout, while Duncan makes clear that his accounts are based on his own experience and opinions, he also cites sources from newspaper stories, official reports, and the memories and opinions of others. He’s modest about his achievements, contrite about failures, and gives credit to others for their successes. Writing the book, he admitted, was not only cathartic for him but helped him step back to reflect and realize that those currently serving are sincerely dedicated to addressing issues and often as challenged and frustrated as he was.

About oil taxation he writes. “I often think about how the erosion of oil tax revenues to the state began with the coup of 1981. I wish I could have prevented that, but it was not to be. … Why don’t those demanding ever-increasing dividends advocate just as fervently for an oil taxation policy that would bring the state its fair share of oil revenues? That would result in a larger dividend and have direct benefit for all Alaska residents.”

The Permanent Fund gets a chapter of its own, unmasking many of the myths that have grown up around its establishment and purpose. Too many of today’s Alaskans believe that the fund was created to share oil wealth with individuals. Duncan, involved as a House member at the time, clarifies, “The original intent was to set up a fund to generate earnings that could be used in future years to help support critical government programs and services.” He presents the early efforts to establish such a fund and then, after the constitutional amendment was adopted in 1976, the debates over how the fund should be invested and managed, the creation of the dividend program in 1980 and the repeal of Alaska’s income tax the same year, and the continuing debate about the size of the dividend.

Other topics covered by Duncan in his well-organized and clearly written 31 chapters include his constant battle against moving the capital out of Juneau, the Mental Health Trust, health care, caring for seniors, and funding public education and the university. Later chapters delve more into process — the “finance and budget game,” crafting laws, sticking to unpopular principles, debate dilemmas and strategies. He also gives a lot of attention to what he refers to as “defined benefit pension betrayals,” laying out the reasons for the end of that system and the results we see today. He explains the major miscalculations and cover-up by the hired actuaries that led to the change to a “defined contribution” system, which only one other state has embraced.

An important point that Duncan makes throughout “Making Sausage” is about the need to get along with others and work in a bipartisan manner. After the 1981 coup there were plenty of hard feelings, but Duncan and other legislators went back to work, rebuilding trust and putting the interests of Alaskans first. There should be lessons here, not just for Alaskans of any age and stripe, but for politicians and citizens everywhere.

[Here are 6 new and noteworthy books for October]

[Book review: ‘Secret Alaska’ is a handy guide for the uninitiated explorer]